In an effort to present Leon and Michaels story objectively and accurately, we have relied on first-person interviews and archival material. Quotes from our interviews, which we conducted over a two-year period from 2011 to 2012, appear in present tense. When quoting from secondary sources such as books, newspapers, and magazines, we have provided attribution within the narrative.

IT STARTED AT A DEAD END IN ST. LOUIS.

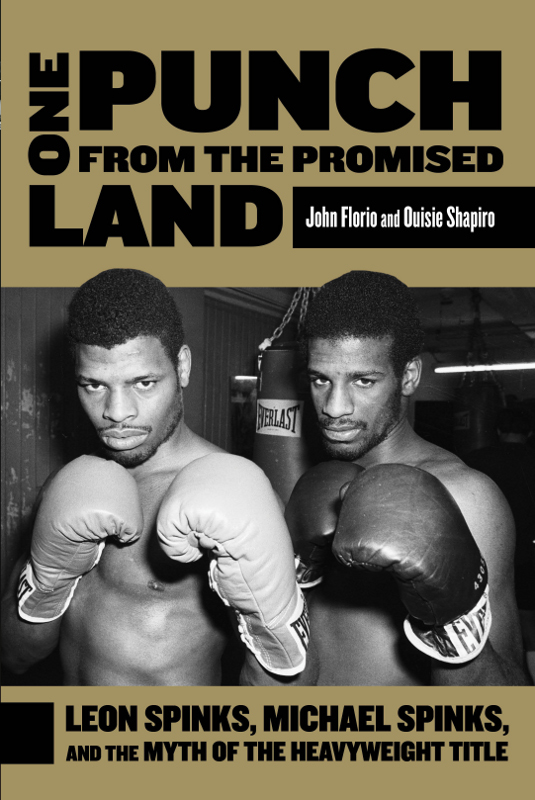

One block from the rats, roaches, and junkies roaming the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, dozens of kids exercised in a square one-story brick building with broken plumbing, finicky heat, and a makeshift boxing ring set up on a volleyball court. This was the DeSoto Rec Center, and a glance around the room revealed the usual faces: Jesse Davison skipping rope, Harold Petty smacking the speed bag, James Caldwell sparring in the ring. Another regular, an eighteen-year-old with a thick neck, strong back, and nose for mischief, was pummeling the heavy bag. He hammered it so ferociously that the rest of the kids wouldnt dare get in the ring with him. His brother, a lanky teen three years younger and an inch taller, quietly shadowboxed in the corner. He had the look of a young pony learning to take its first steps. Leon and Michael Spinks had come to the DeSoto for the same reason as the others: to learn how to defend themselves on the streets they called home.

Pruitt-Igoe was no ordinary housing disaster. It was Mean Streets and New Jack City, circa 1971. It was an urban-American Lord of the Flies. And from the day the ribbon was cut on the first twenty of its thirty-three towers in 1954, it had been a lie.

The complex was a mile from the Gateway Arch, the citys iconic centerpiece, and had come with a promise direct from the St. Louis Housing Authority: Pruitt-Igoe would mark the end of the urban slum.

The cluster of nearly identical eleven-story glass and concrete erections was supposed to replace the decrepit row houses that had become an eyesore. The hype machine was cranking. The ads for Pruitt-Igoe presented a community straight out of Ozzie and Harriet and interiors worthy of Better Homes and Gardens magazine.

Bright new buildings with spacious grounds, the ads read. Indoor plumbing, electric lights, fresh plastered walls, and other conveniences expected in the 20th century. It wasnt long before other major citiesBaltimore, Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Bostonwere modeling their own urban-renewal projects on the Pruitt-Igoe prototype.

But the developers had been skimping on materials from the start. Pruitt-Igoe was falling apart before the tenants had a chance to move in.

Worse yet, racial conflict was pulling at the seams of St. Louis, and Pruitt-Igoe only heightened the tension. The project itself was segregated: Pruitt Apartments were meant for black residents, Igoe Apartments for whites. Only when the Missouri Federal District Court ordered the desegregation of St. Louis public housing in December 1955 did the city tear down the projects invisible walls. Faced with the prospect of living in an integrated complex, white tenants backed out en masse. Black tenants with any other option followed. Only the poorest of black families remained.

When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, two years and ten months into office, his successor Lyndon Johnson vowed to carry through Kennedys social programs, which were designed to address the very issues plaguing Pruitt-Igoe.

President Johnson addressed Congress in March 1964: I have called for a national war on poverty. Our objective: total victory Because it is right, because it is wise, and because, for the first time in our history, it is possible to conquer poverty, I submit, for the consideration of the Congress and the country, the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964. The act does not merely expand old programs or improve what is already being done. It charts a new course. It strikes at the causes, not just the consequences of, poverty.

Johnson didnt stop there. His administration was behind the Civil Rights, Food Stamp, and Fair Housing Acts. It introduced local health-care centers and nationwide urban-renewal projects. And it pushed through an unprecedented amount of anti-poverty legislation, including Job Corps, VISTA (Volunteers Service to America), Upward Bound, Head Start, Legal Services, and the Neighborhood Youth Corps.

But none of these programs made it to Pruitt-Igoe. North St. Louis offered its residents only two significant employers: the Brown Shoe Company and a General Motors plant that turned out the Caprice, the Impala station wagon, and the Corvette. Both factories systemically shut black workers out of skilled trades and confined them to menial jobs such as porters, sweepers, and material handlers. As such, unemployment among blacks in north St. Louis hovered at 19 percent. The only tangible impact Johnsons dream of a Great Society had on Pruitt-Igoe residents was that they now had a new label: the hard-core poor.

By the late 1960s drug dealers commanded the street corners, desperate junkies habitually ripped copper pipes from the walls, and armed vandals controlled the common areas. Residents ran for their lives, leaving two-thirds of the apartments empty. Life in Pruitt-Igoe became so precarious that cops patrolling the area stopped answering emergency calls coming from the tenants. The gangs grew stronger and the murder rate in north St. Louis soared, soon doubling that of New York City and eclipsing that of the rest of the country. The press reported crime in Pruitt-Igoe as black versus black. A more accurate description may have been gangs versus anybody left.

Michael and Leon lived the way most everybody who was stuck there did: in fear. How bad was it? For starters, the original plan called for skip-stop elevators, so by design, the lifts stopped at every third floor. A cost-saving measure, it was billed as a way to encourage residents to congregate in communal spaces. But the foul, urine-stained elevators rarely worked, and the squalid common areasespecially the desolate stairwaysbecame dangerous pockets of crime. For most residents, there was no safe way to get home, other than scaling the side of the building with a pick and a rope.

Pruitt-Igoe was a terrible place to live, remembers DeSoto boxer Jesse Davison. No guys would come to fix the elevators cause they were afraid. I lived on the eleventh floor, but I didnt ride the elevators. I walked up the steps. Youd ride in the elevator, the lights would be broken. If you got stuck, youd try to climb out the top, but you didnt know what would be waiting. Thered be drug dealers on top of the elevator. Youd be afraid theyd shoot at you, urinate on you.