PLAINS SONG

For Female Voices

WRIGHT MORRIS

INTRODUCTION TO THE BISON BOOKS EDITION BY

Charles Baxter

1980 by Wright Morris

Reprinted by arrangement with Josephine Morris

Introduction 2000 by the University of Nebraska Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Bison Books printing: 2000

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morris, Wright, 1910

Plains song: for female voices / Wright Morris; introduction to the Bison Books edition by Charles Baxter.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-8032-8267-2 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. WomenGreat PlainsFiction. 2. Mothers and daughtersFiction. 3. Great PlainsFiction. I. Title.

PS3525.O7475 P5 2000

813.52dc21

00-033784

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8032-8331-2

INTRODUCTION

Charles Baxter

The Japanese have a wordsabithat refers to any object that after many years has acquired a quality of what we might call noble shabbiness. This noble shabbiness might be imagined as the weathering of a piece of furniture that has been worn smooth by use and age. Nothing you buy at the mall can possess sabi. Only those objects that have been worked and touched for a long time can have it. Sabi is found not in the beauty of youth but instead in the beauty of wear and tear, the beauty of something that has stood the test of time and is still standing in spite of everything. Sabi is the acquired soul of a created thing as it grows old.

Readers unfamiliar with the writings and the photographs of Wright Morris should be on the lookout for that quality in Plains Song, but its presence here does not fully explain the special beauty of this narrative, which on its surface is an account of three generations of women (and a few of their men) living on the plains in Nebraska. Be warned: the book and its characters may appear to be simple, but this narrative is somewhat devious, and some of its treasures may remain hidden from the casual reader. Plains Song is a wonderfully strange novel and only gets more strange and beautiful the more you look at it, like a photograph that slowly reveals its truth under very close inspection. It gives us a set of characters, carefully and lovingly preserved, who in their habits of thought and behavior may seem rather unfamiliar and even odd, given their distance from us. Most of them possess a human form of sabi, and they live among objects that have acquired it as well.

Morriss characters are defined more by silence than by speech, more by work than by pleasures takenand by a sense of privacy so severe that not even the novels narrative will violate it. Short as it is, the novel takes its time, and time, finally, is one of its major subjects.

Wright Morriss fictiona major achievement in American letters in this centuryspanned the interval from the publication of My Uncle Dudley in 1942 to that of the novel you hold in your hands, published thirty-eight years later. Plains Song was Morriss last major work of fiction, and it looks and feels a bit like a testament, a compendium of much of what its author had known and seen and thought about for a considerable part of his life. A twilight effect hangs over it, as does the sense that events are being viewed from a middle distance by someone who was once a part of the scene he describes but is no longer. At the same time, the book is particularly relevant to many of our contemporary concerns, particularly to our ongoing discussions of the power relationships between men and women. In its own way, Plains Song could be called a feminist narrative, though its feminism is not exactly like anyone elses and has no clear agenda. For one thing, the word love almost never appears in this novel. Its characters may sometimes feel love, but it is nobody elses business if they do, including the readers. Plains Song is not that kind of book. Marriages do take place here, but they are as accidental as an exposure to poison oak.

The author of this text was born in Nebraska, and though he lived most of his life away from the Midwest and was as sophisticated and worldly a writer as anyone might imagine (he wrote more than a dozen novels, several volumes of literary criticism, and four photo-texts, one about Venice), he seems to have been most deeply possessed by the local details and habits of thought with which he was surrounded as a child. In this respect he may resemble his fellow Nebraskan Willa Cather. His fiction treats down-home subjects with a great technical cunning, with the result that his characters are neither falsely enlarged to heroic proportions nor ironically diminished by condescension. It may seem like an odd thing to say, but his characters always appear to be about the right sizethe narrative always manages to get their proportions right. (In an age of television, movies, and hype, this achievement is more uncommon than you might think.) To get them right, the author does not love his characters by gushing over them; instead, he does them the honor of paying close attention to them. His novels are, therefore, acts of lyrical attention rather than high dramas, and a good reader might do well to bring a close attention to what Morris has set down, with such precision and care, on the page. He liked slow readershe said so many timesand those who took careful notice.

In one of his books of photographs, he wrote that it was his aim to salvage what I considered threatened, and to hold fast to what was vanishing. In some sense, he was the novelist as collector, a preservationist, a person on whom very little would ever be lost.

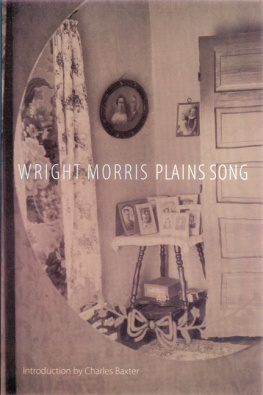

Reading slowly then let us start with the photograph that appears again and again throughout this book. Morris was a remarkable photographer, as Ive noted, in addition to being an outstanding writer of fiction, and he has affixed one of his own photographs to the beginning of each chapter. This photograph, Reflection in an Oval Mirror, Home Place, 1947, (though it is not labeled as such in the novel) apparently presents us with a domestic scene. But it is something of an optical illusion. We must take a closer look at it.

At first it appears to be a wavery shot of a bedroom or parlor corner, with a door to the right. After a moment, however, we see that we are looking at a reflection in a mirror whose lower edge embellishes the image with an engraved ribbon on the glass. So far, so good. But one of the novels characters believes that mirrors are suspect by nature. What is there to suspect? In this mirror we glimpse, reflected, a table with several photographs propped up on it, standing beneath two photographs on the wall, the one of a young couple, the other of two children, a girl and a baby. We are looking, then, at a photograph of a mirror reflecting back other family photographs, resulting in a wheels within wheels effect. The old mirror further ages the already aging objects that it reflects, through an effect of minor optical distortion. Its not a smooth, modern mirror, after all, but an antique one, flawed from the time of its creation. Already this photograph seems to be a portrait of familiar objects that subtly hold time within themselves and are somehow, thanks to the medium of reflection, unfamiliar. But what really compels the viewers attention is the door on the right-hand side.

Before we convert this door into a symbola passageway to a different life, an opening to a new future, to love or deathwe should look more closely at it, because something is wrong here. The door is casting a shadow on the wall behind it. Also, it is weirdly placed: too near to the table of photographs to swing open, and with its hinges attached to nothing but air. To speak plainly, the door in Morriss photograph is not a functioning door at all but a piece of wood stored in a room. What at first seems to be a doorway out of the room is in fact a wooden door propped up against the opposite wall. So, in actuality, its a door that leads nowhere, but the

![Wright - One with others : [a little book of her days]](/uploads/posts/book/77095/thumbs/wright-one-with-others-a-little-book-of-her.jpg)