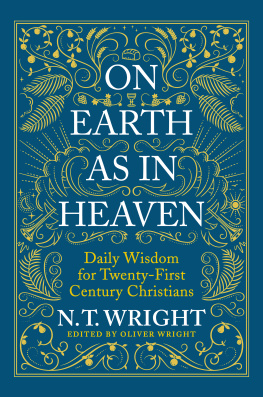

N. T. WRIGHT

For Keith and Margaret Weston

PART ONE: FAITH IN A GREAT GOD

.... 15

....... 25

......... 33

........ 41

........ 45

...... 59

....... 65

....... 75

PART TWO: FAITH TO LIVE AND LOVE

....... 83

....... 89

....... 103

...... 113

...... 121

....... 127

...... 131

PART THREE: FAITH TO WALK IN THE DARK

.... 141

..... 149

....... 153

...... 157

........ 167

.......... 173

.......... 174

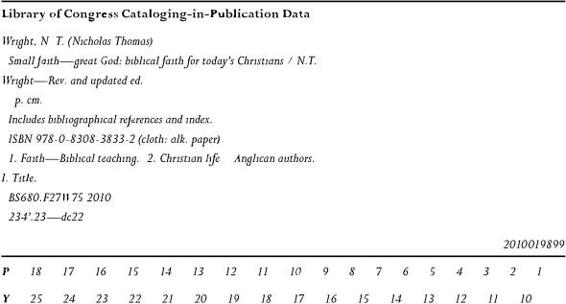

I WAS NERVOUS ABOUT REPUBLISHING these studies, which started out as sermons in and around Oxford. I was still in my early twenties when the first of them was preachedchapter five in this book, preached on Trinity Sunday 1972 in St. Ebbe's Church and the thought of revisiting after forty years the things I had been trying to say, and the way I had been trying to say them, was somewhat daunting. A bit like looking at old photographs: Did we really have those hairstyles? Those clothes? Those cars?

Well, yes, we did. I had something of that sense in rereading these sermons. We thought they were all right at the time, of course-the hair, the clothes, the cars and the sermonseven though they now feel in some respects embarrassingly dated. But I was also surprised to discover that quite a few themes which I had thought were more recent additions to my thinking were already there in embryo. I think, for instance, of the discussion of hypocrisy in chapter ten, which goes closely with my book After You Believe. There are several other connections which the curious reader of my work might tease out.

But what I was really glad to discover was not only that I substantially agreed with so much of what I had written all those years ago, but also that a wealth of memories came flooding back: people and occasions, friends and family, the support and encouragement of so many as I started out on the long and winding journey of ministry, of studying the Bible and trying to preach from it. I have mentioned St. Ebbe's Church in Oxford; the other place which heard many of these sermons was Merton College Chapel. Keith Weston, the then rector of St. Ebbes, and Mark Everitt, the then chaplain of Merton, were and are very different people, from very different sections of the Church of England. But both gave me the space to explore new ideas and preach about them. That was a great gift. The fact that it's hard to tell, without some other clue, which sermons were preached in which of the two places indicates, I hope, that fresh biblical exposition belongs to the whole church, not to one party or strand.

There are, of course, several features which do indeed look decidedly dated. Nobody supposed in those days that spanking naughty children constituted "child abuse." And I realize, in particular, that my more recent work on the ultimate Christian hope (as in The Resurrection of the Son of God and Surprised by Hope) needs to be brought to bear on what I say about "heaven," especially in chapter nine and also, for instance, the final chap ter of this book (which I remember writing frantically one summer Sunday in Oxford, after hours of writer's block and urgent prayer, before cycling the two miles to Merton College at breakneck speed, arriving just in time for the service). And I have changed my mind about some things: for instance, analysis of the Pharisees in chapter ten, and the place of Paul's imprisonment in chapter eleven.

But I don't think that the emphasis I would now place on new heavens and new earth (rather than just "heaven") makes much difference to the main thrust of the book. The greatness of God the Creator and Redeemer is what matters. Our little faith grasps now this aspect of his greatness, now that. But it is God himself who counts, not our perceptions or understanding of him, not our faith or our rhetoric or our pilgrimage. I hope and pray that this little book, period piece though it be, will still be able to make that point clear.

"I'D LOVE TO BE A FLY ON THE WALL when that happens!" So we often say, wishing we could be present at some important meeting or could listen in on some high-level discussion. Well, we're going to begin this book by becoming flies on the wall at a scene of great beauty, as well as of great significance for our understanding of God, of the world and of ourselves. Like all eavesdroppers, we may be in for a few surprises.

The scene is set for us in the fourth and fifth chapters of the book of Revelation. If you find the picture confusing to begin with, you are not alone. All these beasts and crowns and thunder and lightning you may be tempted to dismiss the whole thing as so much incomprehensible mumbo jumbo. Please don't. Revelation isn't mumbo jumbo: it's written in symbols, and once you understand the symbols most of the problems disappear. Of course, nobody understands them all, or per fectly, but we can make a reasonable job of it.

With language like this we have to stop thinking of it as if it were a photograph of heaven as though such a thing were possible! Revelation is more like a map: and a map, once we learn the symbols it uses, is actually of more use to us than an aerial photograph would be. We don't imagine for a moment that when we are climbing a hill we will actually see the contour lines as we cross them on the map. And if we are driving down a road and turn off on a side road, the road is unlikely to change color the way it does on the map. But contours and road colors are not useless. They tell us important facts about where we are going. We would be lost without them.

Next page