Copyright 2009 by Quirk Productions, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Number: 2009922322

eBook ISBN: 978-1-59474-746-5

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-59474-402-0

Trade paperback designed by Doogie Horner

Illustrations by Mario Zucca

Trade paperback production management by John J. McGurk

Quirk Books

215 Church Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

www.quirkbooks.com

v3.1

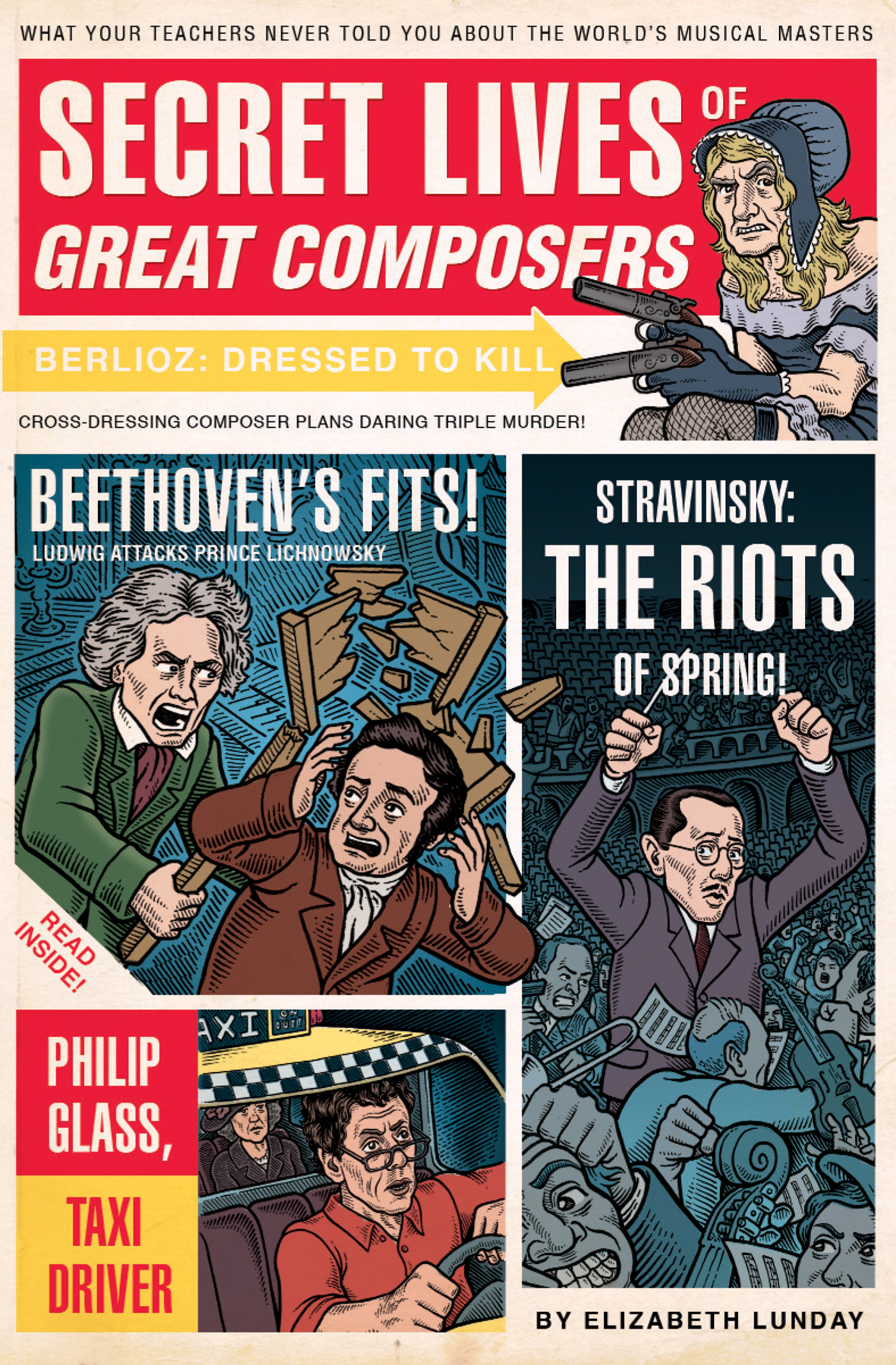

Y ouve checked your coat, handed in your ticket, and settled into your seat for an evening at the concert hall or opera house. You open the glossy printed program and turn to the notes to get some sense of the cultural enlightenment the evening has in store. Reading that erudite text, it is easy to come away with the idea that all composers pursued lives of moral rectitude and personal honor, one worthy of the refined attention about to be given their masterpieces.

Er, not so much. The idea of the outrageous musician is much older than rock and roll. Trashing hotel rooms? Beethoven could wreck a suite like nobodys business. Scandalizing audiences with sexual shenanigans? Liszt had passionate fans from Brussels to Budapest. Demanding concessions from concert promoters? They dont get much weirder than Wagner.

In fact, a lot of composers led truly outrageous lives. Mozart had a potty mouth, Schumann had syphilis, and Bernstein had an ego bigger than New York City. Bach wrote The Well-Tempered Clavier while locked up in the clink, Wagner cranked out Lohengrin while on the run from creditors, and Puccini crafted Madama Butterfly while trying to keep his wife from hunting down his (latest) mistress.

None of those details will turn up in that dull and well-intentioned concert program. So you have this book instead.

For Secret Lives of Great Composers , I hunted down the most outrageous and outlandish stories about some of the most remarkable composers of Western culture. This book wont tell you what to listen for in the fourth movement of some symphony or other, but it will tell you who tried to murder his ex-fiance while dressed drag, who became a world authority on mushroom identification, and who shared compositional credits with his pet rabbit.

Of course, I had room for only a limited number of composers, so dont be hurt because I left out Holst, Offenbach, or Rimsky-Korsakov. This book isnt about musical significance, and Im not judging quality. And please dont let the dirt on your favorite composer get in the way of your enjoyment of the music. Beautiful melodies, haunting chords, and glorious choruses canand havebeen composed by truly outrageous people, and the impact of the music is in no way lessened by a composers oddities or aberrancies.

That said, the conductor has taken the stage, the lights have dimmed, and the conductor has raised the baton. You might want hold on to your seatits going to be a bumpy ride.

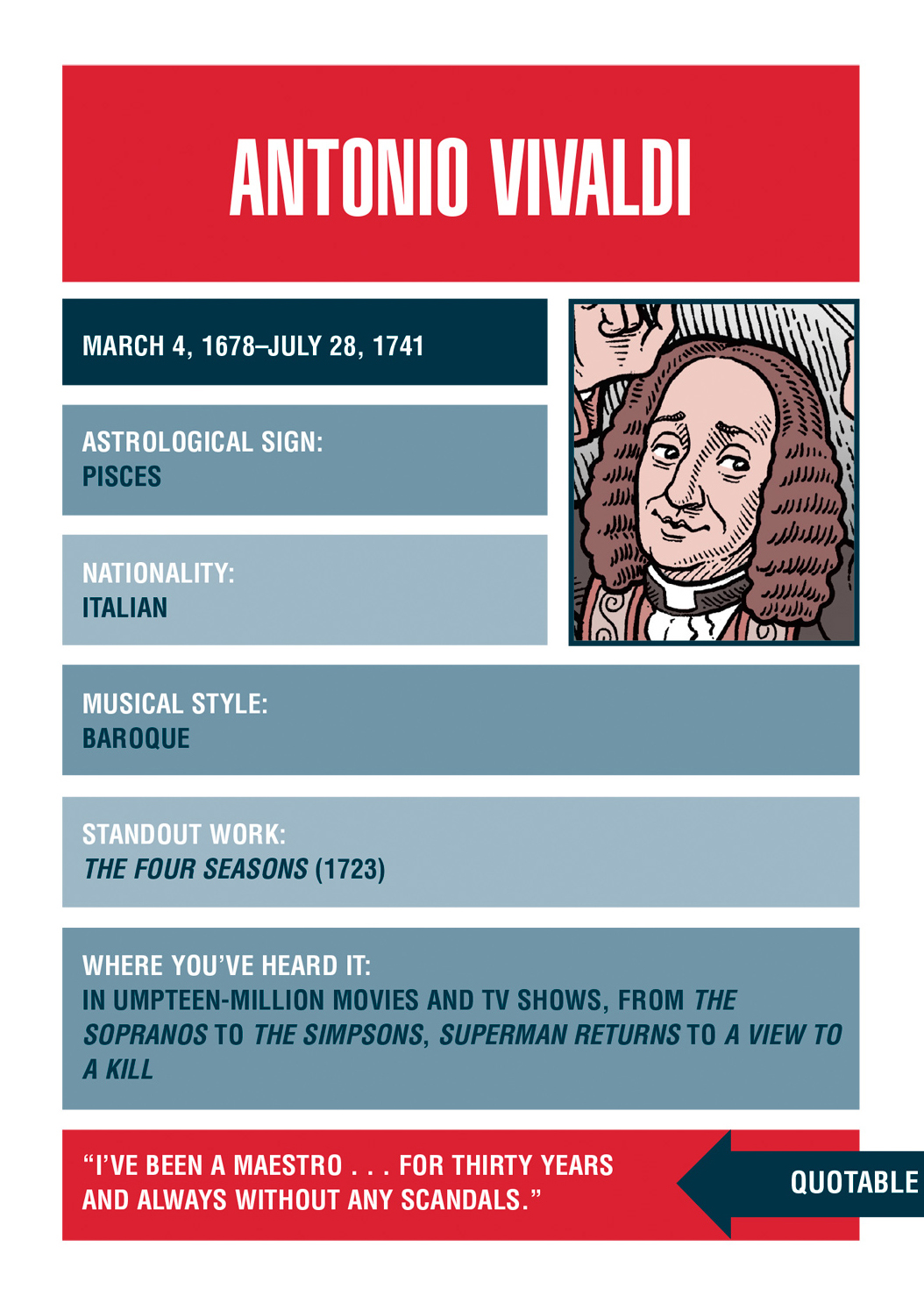

I n his day, Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was known far and wide as the Red Priest for his distinctive red hair and early training as a clergyman, but music lovers today know him best for the omnipresent strains of The Four Seasons piped everywhere from elevators to movie theaters.

Born into a family of meager means, Vivaldi had as little control over his future priestly occupation as he had over his hair color. When he was a child his parents decided he should enter the clergy, but this career path certainly wasnt his choice. His interests were always and only music. Fortunately for him, the priesthood never much got in his way. A convenient asthma condition excused him from priestly duties but somehow never interfered with his directing concertos or putting on operas.

Nor did the priesthood prove a stumbling block for other, fleshier interests, if the gossip around Venice is to be believed. The scandal of Vivaldis life was his attachment to a soprano singer better known for her attentiveness to her vocal coach than for her singing talent. In the end, Vivaldis loyalty to his student/lover would drive him from the country where he had enjoyed a successful career and into penury and eventually to his death in a strange land.

Reluctantly Religious

Vivaldi entered the world in a precarious stateapparently born premature, church records note he was baptized at home, being in danger of death. He pulled through, although he remained sickly all his life. The eldest in a family of three sisters and two brothers, Vivaldi studied violin with his father, Giovanni Battista Vivaldi, who had started off as a barber but ended up as a professional musician in a local orchestra.

But life as a violinist back then promised even less financial security than it does today, and the impoverished family decided their oldest son should enter the priesthood. How Vivaldi felt about this decision we dont know, although he certainly took his own sweet timea full ten yearstraining for the cloth. Nor did he seem to enthusiastically embrace his new duties. Apparently he presided at church services for only a year when tightness in the chest forced him to give up saying the Mass. It should be noted that this tightness, today believed to be asthma, never posed a problem while he was conducting.

Girls, Girls, Girls!

By his twenties, Vivaldi had built a reputation as an accomplished performer and composer, and in 1703 he became a music teacher at the Ospedale della Piet. The Piet was an orphanage for girls, many of whom were the illegitimate daughters of the citys wealthy and powerful men. With ample support, much of it provided by conscience-stricken parents, the Piet included an excellent choir and orchestra that was one of the main attractions of Venice. Tourists from across Europe came to gawk at young girls who not only played such ladylike instruments as the flute but also pounded away at manly kettledrums.

Presumably Vivaldis priestly status made him a safe choice for instructing so many young women. In addition to serving as music director, he churned out some four hundred concertos for the Piet orchestra over the next thirty-five years (although the twentieth-century composer Stravinsky once claimed Vivaldi actually wrote one concerto four hundred times). Among these is Vivaldis most-remembered work, The Four Seasons. Composed in 1725 and based on four sonnets apparently written by the composer himself, The Four Seasons is Vivaldi at his best: charming, imaginative, inventive, and undemanding. Audiences loved it from the startKing Louis XV of France was a particular fan, so much so that his courtiers put on a special performance of the Spring movement just to keep him happy.

But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct

As much as Vivaldi seems to have thrived while writing for the Piet, he had set his sights on a larger goal: composing for the opera. Opera had been invented in 1607 by the Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi in an attempt to re-create the musical style of the Greeks, who had incorporated music, dance, and acting into their dramas. The sights and spectacles of this new form of musical diversion immediately took off, particularly in Italy.