ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

All photo insert images in the public domain unless otherwise noted.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

I like this thing because its a revolt, and Im for revolt every time.

ARTHUR YOUNG, AMERICAN ARTIST

March 1913

New York City

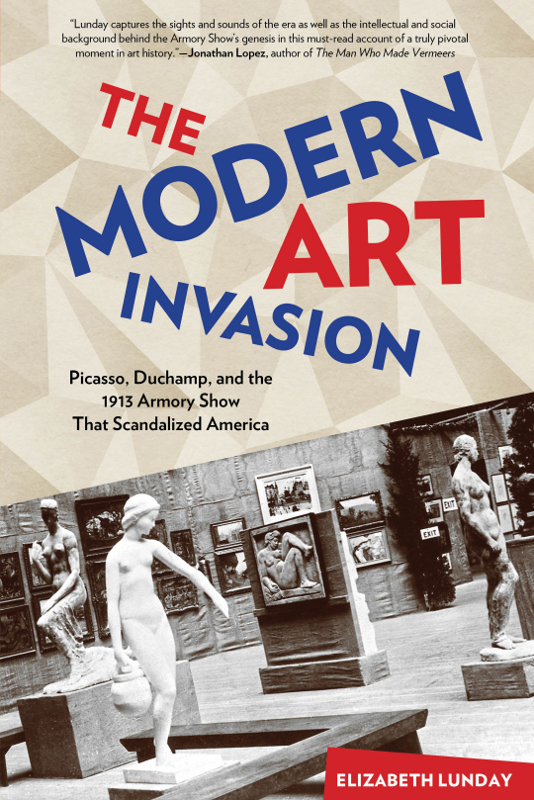

Traffic backed up for blocks around the 69th Regiment National Guard Armory on the east side of Manhattan. Limousines, taxis, and old-fashioned horse-drawn carriages fought for position on Lexington Avenue. Under the baleful glare of beat cops, uniformed attendants wearing spiffy caps shouted into megaphones in a vain attempt to keep traffic flowing. In the line that snaked around the corner and down the block, visitors craned their necks to see how close they were getting to the wide stairs leading to the entrance. They were willing to wait.

Officially, they were attending the International Exhibition of Modern Artbut everyone was already calling it the Armory Show. It was, by far, the most anticipated and talked about event of the season. Everyone wanted to see it.

Inside, staff members checked coats and handed out catalogs; sales staff talked up potential buyers; and art students studied gallery maps to be sure they could handle their guide duties. The high ceiling echoed with conversation and laughter. A few officers of the 69th Regiment wandered around, marveling at the transformation of their drill hall, which was now filled with paintings and sculptures and decorated with potted pine trees and swags of greenery. One newspaper critic said the hall resembled an Italian garden.

Clutching their programs, visitors entered the galleries and moved between brilliantly colored paintings that were unlike anything seen in the United States before: A bullfight by douard Manet. Green olive trees against a pale blue sky by Vincent van Gogh. An old woman counting rosary beads by Paul Czanne. The farther from the entrance, the stranger the art became. A drawing of interlocking charcoal lines by Pablo Picasso was inexplicably titled Standing Female Nude. A jumble of gray and orange blocks claimed to depict a religious procession in Seville, and a chunk of plaster was identified, unaccountably, as The Kiss.

The visitors shared their frank opinions of the art. If I caught my boy Tommy making pictures like that, Id certainly give him a good spanking, announced one matron to her friends.

In one of the last galleries, a crowd piled up around one painting, an arrangement of tan slabs and wedges descending diagonally across a brown background. The catalog identified it as #241: Nu descendant un escalierNude Descending a Staircaseby Marcel Duchamp. One guest stood peering at the work as an art student wearing an Information pin on his lapel tried desperately to explain it.

The visitor shook his head at the end of the students spiel. It may be all as you say, he said, but I fail to discover anything like a girl going down stairs.

Dont let that worry you, broke in another guest. Shes going down so fast you cant see her. Dont you notice the smoke?

Some mocked the strange new art, but other visitors were delighted by the work on display. A journalist encountered Arthur Young, an artist with drawings in the show, cheerfully wandering the galleries. You know, I like this thing because its a revolt, and Im for revolt every time, he said. These post-impressionists and cubists and futurists are throwing figurative bombs. Let em go!

Young wasnt the only one to describe the Armory Show in military terms, perhaps inspired by the martial location. The headline for the New York Herald declared Flying Wedge of Futurists Armed with Paint and Brush Batters Line of Regulars in Terrific Art War. The article went on to say, The battle has been raging in Europe for years, and now the fighting

The American Art News called the art exhibit a bomb from the blue and critic Hutchins Hapgood, writing for the Globe, described the city in ruins as if from an assault: Immense conflagrations, terrifying and exciting fires burst out all over the city. The skyscrapers of prejudice were shaken and the static buildings of outworn tradition were set on fire. Hapgood believed the show would infuse American art with new energy: It is the most life enhancing exhibition of a large and inclusive character that we have ever had in New York. Opponents to the show took a contrary viewthey felt as if their homeland was under invasion by a foreign artistic force and took up arms to defend America from the besieging Cubists, Futurists, and Fauvists.

The first thing to know about the Armory Show is that it was huge. In the 69th Regiment drill hall were 1,200 to 1,300 paintings, sculptures, and drawings. Featured were the works of nearly 300 artists, both American and European, ranging from painters with household names (van Gogh, Picasso, Claude Monet) to artists so completely unknown to this day that art historians can tell us neither the dates of their births and deaths nor even, in a few cases, their full names. The exhibit visited three cities in AmericaNew York, Chicago, and Bostonand nearly a quarter of a million people saw the show. Guests included artists, writers, architects, and poets; queens of society and titans of industry; political heavyweights and marginalized radicals; shopgirls, chauffeurs, bartenders, and students.

Newspapers, the sole mass media of 1913, covered the show from start to finish. Headlines appeared not only in the three tour cities but also across the United States in papers from Grand Rapids to El Paso, Tacoma to Cleveland. The blanket coverage sparked trends in more than just art. Cubism, a narrowly defined art movement in Europe, became a catchall term for anything new, fresh, and modern. Designers unveiled Cubist fashions; hostesses threw Cubist parties where their guests played Cubist games and ate Cubist food. To use a twenty-first-century term, Cubism became a meme.

But the real impact of the show came not in fads and fashions but in fundamental transformations within American art. Modern European art established a beachhead in America with the Armory Show, a secure position from which to launch future incursions. More modernism would follow as European artists realized the potential of the market; soon cross-Atlantic trade in radical art became commonplace. In time, museums such as the Whitney, the Guggenheim, and the Museum of Modern Art opened to showcase it. The stage was set for New York to riserelatively quicklyfrom provincial backwater to capital of the art world.

The Armory Show also transformed the lives of numerous painters and sculptors. Duchamp went from unknown French painter, overshadowed by his better-known older brothers, to the most famous European artist in America. He remains well-known to this daymost people with basic cultural knowledge still recognize his name and can identify one or two of his works. For most artists the change was more subtle; the show offered an opportunity to glimpse a wider world of art, a chance to feel part of a community of modernists, a moment to study styles wilder and more thrilling than any they had seen before.