The Armory Show and Its Publications

On the evening of February 17, 1913, with four thousand guests milling around in the eighteen improvised rooms within the shell of the 69th Regiment Armory, the International Exhibition of Modern Art, more familiarly known as the Armory Show, was formally opened to the public. This sensational exhibition, which included examples of the most advanced movements in European art, was the first of its kind held in the United States and was the result of more than a years planning and organization by a small group of artists, the Association of American Painters and Sculptors...

Few of those who crowded the octagonal-shaped rooms formed by a network of burlap-covered panels could have any inkling of the impact that this event would have upon the future of American art. (from The Story of the Armory Show, by Milton W. Brown)

While the 1913 Armory Show left an indelible mark on American art, now, nearly a century later, the story of the show itself is often told shrouded in myth and legend. Amusing tales of bewildered, culturally provincial audiences and outraged critics abound, but tracing the history of the show back to its beginnings, there exists a trove of archival materials which record the facts underlying the legends, and the very intentions of the shows organizers. Among these files of correspondence, press clips and memorabilia, one finds a series of modestly-produced but remarkable pamphlets.

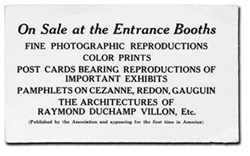

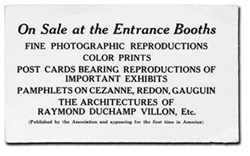

The 1913 Armory Show pamphlets were published by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors in support of the exhibition. The series of four, short booklets comprised of excerpts from artist Paul Gauguins Tahitian journal, Noa-Noa; Odilon Redon and A Sculptors Architecture, by Association member and show organizer, Walter Pach; and Czanne by noted French art historian lie Faure. Printing a reported 5,000 copies of each, the pamphlets were soldalong with postcard reproductions of many of the works on displayat the entrance booths to the New York exhibition (February 17March 15).

While the Association stated its aim for the Armory Show as simply to put the paintings, sculptures, and so on, on exhibition so that the intelligent may judge for themselves by themselves, they were no doubt hopeful of a positive reception for the work. And, definitively on the side of the new art, the show pamphlets were surely aimed to that end. They were aides to better inform the American public about the current European art on view. Theres no record of whether the pamphlets were received that way, but they remain valuable and engaging source documents for consideration today.

When the exhibition moved to Chicago (March 24April 16), the semi-provocative Noa-Noa was withdrawn from circulation by the local exhibition directors on moral grounds. Along with the citys decidedly more conservative atmosphere, press coverage was also lighter and arguably less balanced than it had been in New York. This in mind, organizers Walter Kuhn and Frederick James Gregg (who was acting as the shows public relations director) decided to publish a fifth pamphlet, For and Against.

Referred to as the Red Pamphlet for the color of its cover, For and Against gathered, as one would suspect, essays both for and against the new art. Most of the included pieces had been first published in magazines and newspapers during the shows New York run. Taking the position of for the new art were Frederick James Gregg, Walter Pach, and artist Francis Picabia. Representing the against faction were artist Kenyon Cox and critic Frank Jewett Mather, Jr. Somewhere in between the two camps, and lending a local perspective, came The Chicago Evening Post. Once again, 5,000 copies were printed and sold at the show entrance.

In all, the idea that an exhibitions organizers would publish texts in support of the art works and artists they were showing is not a surprise. Its a practice that thrives to this day in exhibition catalogues, gallery handouts and museum learning guides. To also voluntarily publish views against those same art works and artists, however, is as radical a proposition as one could hope to expect from this legendary show.

Contributors

Kenyon Cox (18561919) was an American painter, writer and teacher. His work is held in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. He is the author of several booksincluding Old Masters and New and Concerning Painting: Considerations Theoretical and Historicaland criticism appearing in The Nation, Century and Scribners magazines.

Arthur B. Davies (18631928) was an American artist, with works in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. He also served as President for the Association for American Painters and Sculptors, overseeing the International Exhibition of Modern Art (The Armory Show) in 1913.

lie Faure (18731937) was a French art historian. Originally trained as a surgeon, Faure was a self-taught art historian and a popular author. His Histoire de lart (first translated by Walter Pach) was a critical and popular hit, and one of the first histories of art to look at arts place in, and relation to, civilization more broadly. Faures other works include, works on Andr Derain and Chaim Soutine.

Paul Gauguin (18481903) was a French painter, though starting with four years spent in Peru when he was a child, and a stint in the marines as a young man, Gauguin traveled throughout his life. In his painting and with the publication of his journal, Noa-Noa, it was his travel to Tahiti that remains his best known influence. Though originally employed as a stockbroker, Gauguins work now resides in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago and other museums around the world.

Frederick James Gregg (d. 1928) was a writer and art critic for the New York Evening Sun. Friendly with artists in the Ashcan School, which included John Sloan and Arthur B. Davies, Gregg later acted as the public relations director for the Association of American Painters and Sculptors and the 1913 Armory Show.

Walt Kuhn (18771949) was an American painter and illustrator, born in Brooklyn, and one of the principle organizers of the 1913 Armory Show. Active in several artist clubs, he was also an instructor at the Art Students League of New York. Though perhaps best remembered for his critical role in the Armory Show, Kuhns art can be found in the collections of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the National Gallery of Art, and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Frank Jewett Mather, Jr. (18681953) was an American art critic and professor. He was a frequent contributor to New Yorks Evening Post, The Nation, and Burlington Magazine. His books include Art in America, Estimates in Art, and Concerning Beauty. He was a professor at Williams College and Princeton University. The College Art Association honors Mather with an annual award in his name, given to a writer for distinguished art criticism.

Walter Pach (18831958) was an artist, art critic, historian and author. A translator and influential adviser on European modern art, Pach helped organize exhibitions and artist groups, as well as purchase work for both private and public collections. His many publications include