Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Librarian, University of Sussex Library for permission to quote from the Leonard Woolf papers; the Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf to quote from On Being Ill, Three Guineas, The Voyage Out, Mrs Dalloway, The Waves, To The Lighthouse, Professions for Women all published by the Hogarth Press; the Executors of the Estate of Virginia Woolf for extracts from The Diary of Virginia Woolf, edited by Anne Olivier Bell (the Hogarth Press), The Letters of Virginia Woolf, edited by Nigel Nicolson (the Hogarth Press), Moments of Being, edited and introduced by Jeanne Schulkind (the Hogarth Press), A Passionate Apprentice: the Early Journals of Virginia Woolf, edited by Mitchell A. Leaska (the Hogarth Press), A Very Close Conspiracy by Jane Dunn (Jonathan Cape); Quentin Bells Biography of Virginia Woolf, vols 1 and 2 (the Hogarth Press), The Autobiography of Leonard Woolf, vols. 1 and 2 (the Hogarth Press), The Letters of Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf, edited by Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell A. Leaska (Hutchinson), Lytton Strachey: the New Biography, by Michael Holroyd (Chatto & Windus); Deceived with Kindness; A Bloomsbury Childhood, by Angelica Garnett (Chatto & Windus); Oxford University Press for allowing extracts of The Prose and Poetry Writings of William Cowper, vol. 1, edited by James King and Charles Ryskamp, Leslie Stephens The Mausoleum Book, introduced by Alan Bell (Clarendon Press); Anny Thackeray Ritchie by Winifred Gerin, and Tennyson by Robert Bernard Martin; John Lehmanns Virginia Woolf and Her World (Thames & Hudson); Orion Publishing for allowing extracts from The Letters of Leonard Woolf, edited by Frederic Spotts (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), Vita and Harold: the Letters to Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson, edited by Nigel Nicolson (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), Leslie Stephen: the Godless Victorian, by Noel Annan (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), Vita: the Life of Vita Sackville-West by Victoria Glendenning (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), and Vanessa Bell, by Frances Spalding (Weidenfeld & Nicolson); David Higham Associates for quotes from Virginia Woolf, by James King, Leonard Woolfs The Wise Virgins (Arnold), Elders and Betters, by Quentin Bell (John Murray) and An Unquiet Mind, by Kay R. Jamieson (Alfred A. Knopf): Professor Pat Jalland at Melbourne University for extracts from Octavia Wilberforce (Cassell) and the Selected Letters of Vanessa Bell, edited by Regina Marler (Bloomsbury).

Preface

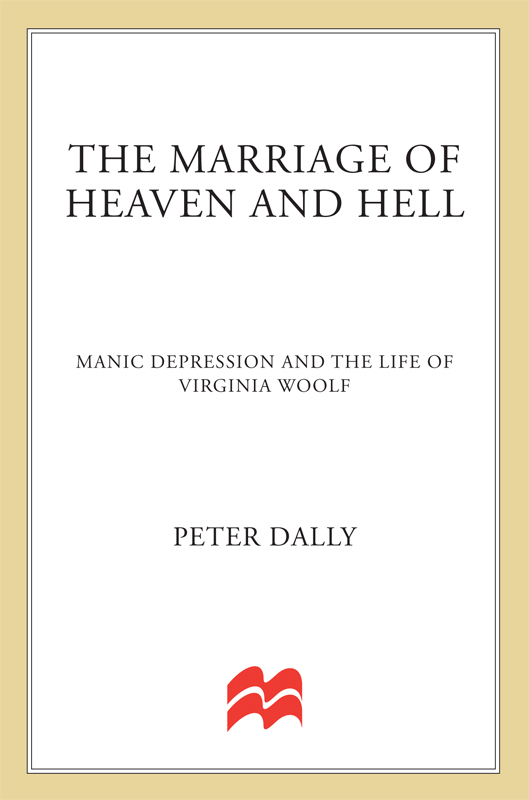

Books on Virginia Woolf continue to flood the market, but an extraordinary gap exists regarding the illness from which she suffered: manic depression. Her diaries surely the fullest year-by-year record ever of the effect of the disease on a creative life, work and relationships and, less reliably, her letters and her husbands autobiography, are wonderfully revealing to the trained eye. Yet each new book, even when written by the medically qualified, fails to reveal the effects of Virginia Woolfs mood swings, and the biological and environmental interactions responsible for them.

The four children of Leslie and Julia Stephen were all talented, and from her earliest years Virginia stood out as the story-teller, the writer, the one who would continue the Stephen literary tradition. For most of the year the family lived in London, but summers were spent in St Ives in Cornwall and were the happiest times of Virginias childhood, their memory kept, squirrel-like, in her creative store. She was highly strung and imaginative, and often difficult, jealously demanding her rights. But in no way unusual; Virginia seemed a thoroughly normal child.

The death of her mother at puberty, followed by that of her half-sister, was devastating, yet she weathered the shock and eventually emerged more or less intact. But during the emotional upheaval, chemicals in the brain that had previously been quiescent stirred into activity and switched on the mental disease that was to influence Virginias life so profoundly over the next forty years.

Manic depression exists in every known society. It was well described by early Greek physicians, but only during the last century has it been defined and separated from other mental illnesses.

The condition showed itself in a yearly cycle of mood changes: depression in late winter and early spring, and then again in September; elation in the summer, sometimes in November. By the time she was 19 Virginia had come to recognise the pattern and told her cousin, My Spring Melancholia is developing into Summer Madness.

Virginias fluctuations of mood between depression and high spirits are known as cyclothymia. At first the mood changes were comparatively mild but, when she was 22, after her fathers death, she became mad and for almost a year was disabled by manic depression. She recovered but in 1913, following her marriage to Leonard Woolf, she had a second, more violent and prolonged attack of madness.

The distinction between cyclothymia and manic depression is one of degree. Any marked shift of mood results in changed feelings and perception. When Virginia was depressed she saw herself as a failure; a failed writer, a failed woman, dwarfed by her sister, Vanessa. She believed she was old and ugly and impotent. She felt people laughed at and ridiculed her. She became afraid of strangers and filled with anxiety. When high or hypomanic, Virginia felt a great mastery over the world,

The deeper the mood swing, the more exaggerated the distortions, and eventually fantasy came to replace reality. In severe depression, when this occurs the cyclothyme becomes insane, or mad, and is diagnosed as having manic depression. The depression which Virginia developed without fail between January and March was potentially the most dangerous. Depression at other times was unpleasant, often incapacitating for many weeks, but never led on to hallucinations. All Virginias breakdowns into insanity had their origin in the New Year period.

Patterns of illness vary individually, but Virginia Woolf had the classic form of the disease: alternating swings of mood occurring with the seasons. Treatment today has improved since her day, but for long-term stability there still remains the need for a trusted understanding partner who can assume temporary command of the patients life at critical times; a need all too often misunderstood by Virginia Woolfs biographers.

Chapter One

Julia Stephen

Virginias mother, Julia Stephen, came from a large family renowned for beauty rather than intellect, and although Julia was often gloomy, even melancholic, she was never seriously depressed, and none of her relatives was remotely insane. It is true that Julias maternal grandfather was a drunk and extravagantly wicked, and that her aunt Julia Margaret Cameron, the renowned Victorian photographer, was a notorious eccentric, but not a manic depressive. Virginias genetic inheritance for cyclothymia came wholly through her father. Nonetheless, Julia contributed a great deal to Virginias temperamental instability and indirectly therefore to her mood swings.

Julia was adored by her husband and children, friends, and the many lame dogs, sick and deprived, whom she nursed and supported. She appeared to one and all the essence of goodness and beauty, a true angel both in and outside the house, always prepared to give of her time to those in need.