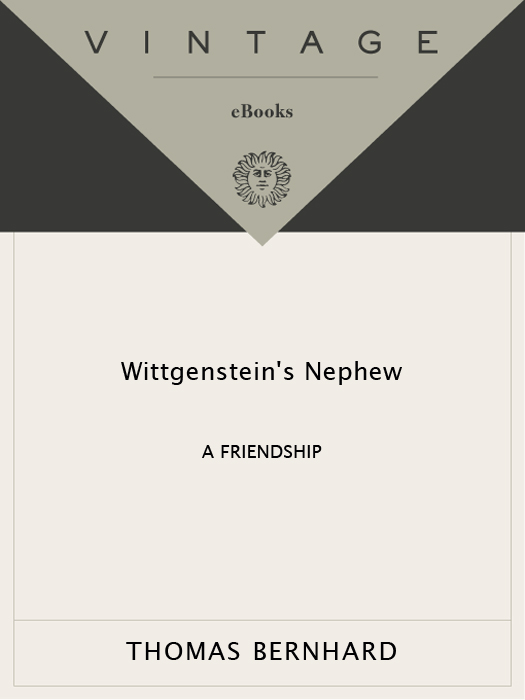

Bernhard - Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship

Here you can read online Bernhard - Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2009, publisher: Knopf Doubleday, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship

- Author:

- Publisher:Knopf Doubleday

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- City:New York

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Thomas Bernhard was born in Holland in 1931 and grew up in Austria. He studied music at the Akademie Mozarteum in Salzburg. In 1957, he began a second career as a playwright, poet, and novelist. The winner of the three most distinguished and coveted literary prizes awarded in Germany, he has become one of the most widely translated and admired writers of his generation. He published nine novels, an autobiography, one volume of poetry, four collections of short stories, and six volumes of plays. Thomas Bernhard died in Austria in 1989.

Concrete

Correction

Frost

Extinction

Gargoyles

Gathering Evidence

The Lime Works

The Loser

Woodcutters

FIRST VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL EDITION, OCTOBER 2009

Translation copyright 1988 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in Germany as Wittgensteins Neffe by Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, in 1982. Copyright 1982 by Suhrkamp Verlag. This translation originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1989.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage International and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Bernhard, Thomas.

Wittgensteins Nephew.

Translation of: Wittgensteins Neffe.

1. Bernhard, ThomasFiction. 2. Wittgenstein, PaulFiction. I. Title.

PT2662.E7W5813 1989

833.914 88045317

eISBN: 978-0-307-83345-7

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

Two hundred friends will

come to my funeral

and you must make a speech

at the graveside.

I N 1967 , one of the indefatigable nursing sisters in the Hermann Pavilion on the Baumgartnerhhe placed on my bed a copy of my newly published book Gargoyles, which I had written a year earlier at 60 rue de la Croix in Brussels, but I had not the strength to pick it up, having just come round from a general anesthesia lasting several hours, during which the doctors had cut open my neck and removed a fist-sized tumor from my thorax. As I recall, it was at the time of the Six-Day War, and after undergoing a strenuous course of cortisone treatment, I developed a moonlike face, just as the doctors had intended. During the ward round they would comment on my moon face in their witty fashion, which made even me laugh, although they had told me themselves that I had only weeks, or at best months, to live. In the Hermann Pavilion there were only seven rooms on the ground floor, accommodating thirteen or fourteen patients who had nothing to look forward to but death. They would shuffle up and down the corridor in their hospital dressing gowns, then one day disappear for ever. Once a week the great Professor Salzer, the foremost authority on pulmonary surgery, would appear in the Hermann Pavilion, always wearing white gloves and walking with an enormously imposing gait, while a bevy of nursing sisters flitted almost noiselessly around him as they escorted him, a very tall and very elegant figure, to the operating theater. This famous Professor Salzer, whom the private patients had to perform their operations, staking everything on his reputation (though I had had mine performed by the senior ward surgeon, a stocky farmers son from the Waldviertel), was an uncle of my friend Paul, the nephew of the philosopher whose Tractatus Logico-philosophicus is now known to the whole of the scholarly world, to say nothing of the pseudoscholarly world. At the very time when I was lying in the Hermann Pavilion, my friend Paul was some two hundred yards away in the Ludwig Pavilion, though this, unlike the Hermann Pavilion, did not belong to the pulmonary department, and hence to the so-called Baumgartnerhhe, but belonged to the mental institution Am Steinhof. Male Christian names are given to all the pavilions on the Wilhelminenberg, which occupies a vast area in the west of Vienna and has for decades been divided into two partsa smaller part, reserved for chest patients and called the Baumgartnerhhe for short (this was my territory), and a larger one, occupied by mental patients and known as Am Steinhof. It seemed grotesque that my friend Paul should be in the Ludwig Pavilion of all places. Whenever I saw Professor Salzer striding purposefully toward the operating theater, with never a glance to left or right, I could not help recalling how, time and again, my friend Paul had described his uncle alternately as a genius and a murderer, and every time I saw the Professor entering or emerging from the operating theater, I wondered whether I was seeing a genius or a murderer entering, a murderer or a genius emerging. This mans medical fame exercised a great fascination over me. Before my stay in the Hermann Pavilion, which is still devoted to lung surgery and specializes above all in lung cancer surgery, I had already seen many doctors and made a habit of studying these doctors, but from the moment when I first saw Professor Salzer, he put all the others in the shade. He was magnificent in every way, and this magnificence I found utterly unfathomable. His persona seemed to consist partly of the man I saw and at the same time admired, and partly of the rumors I had heard about him. According to my friend Paul, Professor Salzer had for many years been able to work miracles: patients who had apparently no chance of survival had gone on living for decades after he had operated on them, while others, so Paul told me time and again, had died as the result of a sudden unforeseen change in the weather under a knife grown nervous. Be that as it may, although Professor Salzer really was a world authority, and at the same time my friends uncle, I did not let him operate on me, precisely because he exercised such a tremendous fascination over me and because his absolutely universal fame filled me with abject terror and made me decide, ultimately because of what I had heard from my friend Paul about his uncle Salzer, in favor of the worthy senior surgeon from the Waldviertel and against the great authority from Viennas First District. During my first few weeks in the Hermann Pavilion, moreover, I had repeatedly observed that Professor Salzers patients were the ones who did not survive their operations; his world fame was doubtless going through a bad patch, and this made me suddenly afraid of him. I therefore opted for the senior surgeon from the Waldviertelwhich, as I now see, was undoubtedly a fortunate choice. But such speculations are pointless. While I myself saw Professor Salzer at least once a week, though at first only through the crack of the door, my friend Paul, who was after all his nephew, never saw him once during all the months he spent in the Ludwig Pavilion, although Professor Salzer certainly knew of his nephews presence and it would have been the easiest thing in the world, as I thought at the time, for him to walk the few yards from the Hermann Pavilion to the Ludwig Pavilion. I do not know what reasons he had for not visiting Paul; perhaps they were weighty reasons, or perhaps he simply found it too much trouble to visit his nephew, who had frequently been a patient in the Ludwig Pavilion, whereas this was my first visit to the Hermann Pavilion. In the last twenty years of his life, my friend had to be admitted to the mental asylum Am Steinhof at least twice a year, always at short notice and always

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship»

Look at similar books to Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Wittgensteins nephew : a friendship and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.