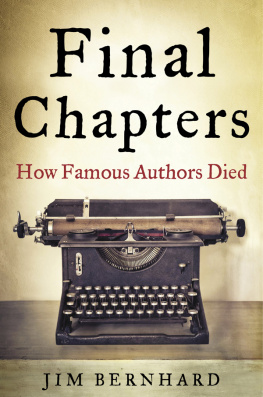

Copyright 2015 by Jim Bernhard

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover photo credit: Thinkstock

Print ISBN: 978-1-63450-241-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-0061-1

Printed in the United States of America

For Ginger

Contents

Last Words First: An Introduction

W HEN WE HEAR that anyone has died, one of the first things we ask is: What did he (or she) die of? And then: How old was he (or she)? Such personal details of death are a source of fascination to most people. Dorothy L. Sayers, who killed off a good many folks in her murder mysteries, said, Death seems to provide the minds of the Anglo-Saxon race with a greater fund of amusement than any other single subject. But she didnt go far enough in her assessment. Its not just Anglo-Saxons who are stuck on death; its the whole human race.

Death has several characteristics that may explain the attention that we lavish on it. It is both inevitable (so far as we know) and unpredictable (in most circumstances). People who estimate such things tell us that since the beginning of the world, about 107 billion people have been born. Of that total, only a little more than 7 billion are alive today. If you do the math, youll find that means that out of everyone who has ever lived, 93 percent of them have died. The odds are not in favor of the remaining 7 percent of us.

The Pulitzer Prizewinning writer William Saroyan once said, Everybody has got to die, but I have always believed an exception would be made in my case. Unfortunately for him, no exception was made, and he died of prostate cancer in 1981. He was seventy-two.

Inevitable as it may be, death is also unpredictable for most of us as to precisely when we might expect it. This quality infuses it with a suspenseful frisson , guaranteeing that we will think about it from time to time.

Nobody has expressed the inevitability of death better than William Shakespeare. Hamlet, who pondered the subject more than was good for him, put it this way: There is a special providence in the fall of a sparrow; if it be now, tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all.

One other quality that gives death a healthy dose of gravitas is its finality. No matter what ones views are about the possibility of an afterlife, theres no getting around the fact that death permanently ends the life were in nowthe only one we really know anything about. The lane to the land of the dead, as W. H. Auden called it, is a one-way street. And its destination, as Hamlet puts it, is the undiscovered country, from whose bourn no traveler returns.

The lives and deaths of the worlds poets, dramatists, and novelists are ideal for studying how humans approach dying. The various ways they shuffled off this mortal coil could fill an encyclopedia of disease and mishap. They were snuffed out by infections (especially in the days before antibiotics); by frequent lung disease (particularly in the nineteenth century, when tuberculosis and pneumonia were rampant); by the expected quotient of heart attacks, strokes, and cancer; by stomach and kidney disorders and a few rare and unknown diseases; plus a fair number of suicides, murders, assassinations, and bizarre accidents. Alcohol, tobacco, and narcotics played leading roles in many cases.

Death came to some in startling ways. The Greek playwright Aeschylus had a fatal encounter with a turtle that fell from the sky. Italian theologian Thomas Aquinas was knocked off a donkey by a tree branch and never recovered. French dramatist Molire was mortally stricken while playing the part of a hypochondriac in one of his own plays. The corpse of the philosophe Voltaire was transported to his funeral dressed in finery and propped up as if he were still alive.

American poet Emily Dickinsons final illness was difficult to diagnosebecause rather than allowing her doctor to examine her, all she would consent to was to walk slowly past the open door of his examining room while he observed her from inside. Writer Sherwood Anderson was felled by an errant toothpick in a martini. Trappist monk Thomas Merton was killed by a fanan electric one. Did poet Dylan Thomas really die of eighteen straight whiskeys? And was it a stray bottle cap, too many pills and too much liquor, or murder most foul that did in playwright Tennessee Williams?

Ages of authors at the time of death have also varied widely. Curiously, even though average life expectancies have substantially lengthened in modern times, writers do not seem to have benefited from the improvement. The average age at death of the classical Greek and Roman subjects in this book was about seventy. Oddly enough, for the authors of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, it was earlierabout sixty-five. Ages at death range from Sophocles at ninety-one and George Bernard Shaw at ninety-four, to Percy Bysshe Shelley at twenty-nine and John Keats at only twenty-five.

This book explores not only the individual causes of death and the circumstances surrounding it, but also what each author might have thought about the end of life. Being writers, most have left at least some clues, if not specific exposition, about their attitudes toward death in their poems, plays, novels, diaries, letters, and interviews. They exhibit a wide range of opinions.

Few if any of these famous authors have had the kind of near-death experiences that have spawned many recent sensational books that often climb to the top of bestseller lists. The array of such alluring titles is dizzying: Proof of Heaven, Return from Tomorrow, My Descent into Death, 90 Minutes in Heaven, Life on the Other Side, Waking Up in Heaven, and Heaven Is For Real are a few of them. One classic author who stands out as an anomaly for his unwavering certainty about the existence of an afterlife is Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmess creator, who insisted that he was able to converse with folks who had passed over to the other side.

For the most part, however, the creators of our literature, from the classical era to modern times, have expressed the same kind of uncertainty the rest of us feel about what to expect from a visit by the Grim Reaper. Like anyone elses, the authors views about death are shaped by their religious and philosophical beliefs, which span the gamut from polytheism and Stoicism in the classical Greco-Roman period; to Christianity, prevalent in the European Middle Ages and Renaissance; to Deist and Transcendental thought, developed in France and America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; to the questioning agnosticism or blatant atheism that pervades the contemporary Age of Anxiety. Attitudes toward death differ widely, ranging from fear to acceptance to indifference.