Mihail Sebastian

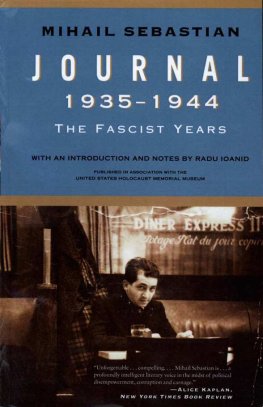

Journal 19351944: The Fascist Years

INTRODUCTION by Radu Ioanid

Forgive me, but I dont believe you, said Woland. That cannot be. Manuscripts dont burn.

Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita

On 29 May 1945, as he rushed to cross a street in downtown Bucharest, thirty-eight-year-old Mihail Sebastian, a press officer at the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was hit and killed by a truck. As it happened, Sebastian was late to an appointment at Dalles Hall where he was to teach a class about Honor de Balzac.

The deceased had been born Iosif Hechter, in 1907, in Brila on the Danube. At the time of his death he was well known in Bucharest literary and political circles as a writer of fiction and of literary criticism, and as the author of several successful plays. His sudden demise left his mother and brothers in a state of shock, while members of Bucharest high society shook their heads in disbelief. As time passed, a few former girlfriends thought fondly of him every now and then; here and there a literary critic mentioned his name; a theatre director occasionally staged one of his plays.

Eventually Sebastians name came to be associated chiefly with his plays, less so with his novels. A far lesser-known contribution to Sebastians legacy, however, was the diary he had written during the period 19351944, and which remained among his possessions when he died. In 1961, as Sebastians brother Benu emigrated from Romania to Israel, he shipped the diary out of the country via the diplomatic pouch of the Israeli embassy. Benu was right to be cautious; many manuscripts before (and since) had been confiscated by the Securitate, the Romanian secret police, only to disappear for many years if not forever.

Sebastians extraordinary diary was published for the first time in full in 1996 in Romanian, followed by a French edition in 1998. The diary was nothing short of a time bomb, its publication generating an explosive debate about the nature of Romanian anti-Semitism in general and about Romanias role in the Holocaust in particular. Vasile Popovici, a literary critic, wrote upon reading the diary, . . You cannot possibly remain the same. The Jewish problem becomes your problem. A huge sense of shame spreads over a whole period of national culture and history, and its shadow covers you, too.

Sebastians diary spans a period that saw the rise of three successive anti-Semitic dictatorships in Romania, each more devastating for the countrys 759,000 Jews than its predecessor. This triad began with the regime of King Carol II (February 1938-September 1940), which was followed by the rule of Ion Antonescu in alliance with the fascist Iron Guard (September 1940-January 1941), and ended with Ion Antonescu as Conductor (Leader), ruling alone after having violently suppressed his erstwhile Iron Guard allies (19411944).

Sebastians diary is not the sole or even the first literary account of the Nazification of European society to emerge from the postwar years. Victor Klemperers diary, published under the title I Will Bear Witness: A Diary of the Nazi Years, 19331945, also recounts the brutal and merciless way in which he was rejected by his native society simply because he was born Jewish. Also like Sebastian, Klemperer recorded and noted the systematic shrinking of the physical and intellectual freedom allowed to him as a consequence of Nazism. Still, while Klemperer wrote as a Jew in the heart of the Nazi Reich in Berlin, he was protected by his wifes Aryan status and his own conversion. Sebastian wrote under Romanian fascism (which was characteristically different from German Nazism) and enjoyed no protection from the onslaught, having no Aryan relatives and refusing to convert. It is worth noting that this seems to have been a matter of principle for Sebastian. Although he felt few religious ties to Judaism, he scorned the reaction of his fellow Jews who saw baptism as the only possible solution to escape deportation: Go over to Catholicism! Convert as quickly as you can! The Pope will defend you! Hes the only one who can still save you. . Even if it were not so grotesque, even if it were not so stupid and pointless, I would still need no arguments. Somewhere on an island with sun and shade, in the midst of peace, security and happiness, I would in the end be indifferent to whether I was or was not Jewish. But here and now, I cannot be anything else. Nor do I think I want to be. At the height of the anti-Jewish persecution in September 1941, Sebastian went to the synagogue because he wanted to be with his fellow Jews: Rosh Hashanah. I spent the morning at the Temple. I heard afran [chief rabbi of Romania] who was nearing the end of his address. Stupid, pretentious, essayistic, journalistic, shallow and unserious. But people were crying and I myself had tears in my eyes.

It is not only in terms of their Jewishness that Klemperer and Sebastian are distinct (and thus too the perspective they brought to their diaries). Perhaps more important was their differing surroundings and the very nature of the fascist movements they endured. If Klemperer survived because of the legalistic technicalities of Nazi definitions of Jewry, Sebastian survived due to the particularly opportunistic nature of the Romanian fascist regime. For like almost half of Romanian Jewry, Sebastian remained alive until 1944 only because in the eleventh hour the Romanian authorities changed their tactics, and even their position, on the so-called Jewish problem. When Marshal Antonescu, and others whose voices counted at the time, realized that Romania, which was allied with Nazi Germany, might not be on the winning side in the war, he and his minions ceased deporting and killing Romanian Jews. Thus Romanian Jewry, which had been targeted for extermination between the years 1941 and 1942, abruptly became a bargaining chip, a means by which the Romanian authorities could hope to buy the goodwill of the Allies and soften the postwar repercussions of defeat. Sebastians diary is, among its many other attributes, a compelling chronicle of the years during which the collective fate of Romanian Jews hung by a thread.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Bucharest, where Sebastian lived and died, was affectionately referred to as little Paris. Filled with charm and personality, Bucharest was also a modern city, electric lighting having been introduced in 1899, one year after the French architect Albert Galleron built the impressive Ateneu Roman concert hall. Beautiful boulevards such as the Calea Victoriei were lined with private palaces and sumptuous hotels, among them the famous Athene Palace. On the same street a New York-style skyscraper owned by ITT faced the popular restaurant Capa. Electric streetcars provided public transportation throughout the city, and elegant automobiles carried their owners to meetings for business or pleasure. Bucharest was cosmopolitan, and its upper classes traveled to Paris and Vienna, dressing in the fashions of the West. An aristocracy in decline and a rising bourgeoisie competed with each other for wealth and prestige, and the symbols of their fortunes and status were very much on display. Modern villas dotted the northern part of the city, near the beautiful Herstru Park. Bucharest had many other wonderful green spaces too, among them Cimigiu Park, copied from New Yorks Central Park, and Parcul Lib-ertapi, designed by the French architect Eduard Redont. Winters were quite cold and summers too hot in Bucharest, but resorts in the Carpathian Mountains and on the Black Sea were only a few hours ride by train or car. Like any other capital city, Bucharest had its share of museums, art galleries, universities, newspapers, public and private schools, and, of course, intellectuals.

Ever a city of contrasts, however, Bucharests high society mingled in the streets with their less fortunate neighbors from the middle class, with barefoot peasants from Oltenia who delivered milk and cheese, and with Bulgarian gardeners who sold fresh vegetables. Quite unlike the city precincts of elegant villas and hotels, Bucharests suburbs contained ugly industrial enterprises and neighborhoods where the lower middle class and poor lived in cheap houses, often situated on unpaved streets. Here and there Eastern markets and a certain way of dealing reminded foreign visitors that little Paris was in fact closer to the Levant than many Romanians wished to acknowledge.