Germany: Jekyll and Hyde

An eyewitness analysis of Nazi Germany

by Sebastian Haffner

Translated from the German

by Wilfrid David

W ith an introduction by Neal Ascherson

Published by Plunkett Lake Press, November 2012

www.plunkettlakepress.com

Estate of Sebastian Haffner

Introduction Neal Ascherson, 2005

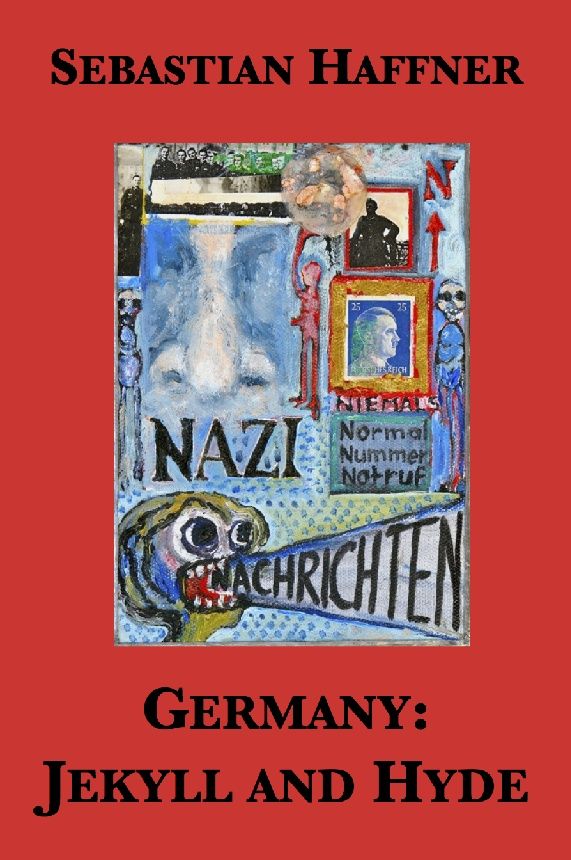

Cover: Susan Erony and Erika Marquardt; Have We Gone Too Far ; one of one-thousand paintings; mixed media on canvas framed in lead; 5 x 7; 1998-2008

First published in Great Britain in 1940 by Seeker and Warburg

Second edition, 2005 by Libris

Paperback edition , 2008 by Abacus

~ Other eBooks from Plunkett Lake Press ~

Also by Sebastian Haffner

The Ailing Empire: Germany from Bismarck to Hitler

The Meaning of Hitler

The Rise and Fall of Prussia

By Sholom Aleichem

From the Fair

By Helen Epstein

Children of the Holocaust

Joe Papp: An American Life

Music Talks: The Lives of Classical Musicians

Where She Came From: A Daughters Search for Her Mothers History

B y Anthony Heilbut

Exiled in Paradise: German Refugee Artists and Intellectuals in America from the 1930s to the Present

B y Eva Hoffman

Lost in Translation

By Peter Stephan Jungk

Franz Werfel: A Life in Prague, Vienna, and Hollywood

By Egon Erwin Kisch

Sensation Fair: Tales of Prague

By Heda Margolius Kovly

Under A Cruel Star: A Life in Prague, 1941-1968

By Peter Kurth

American Cassandra : The Life of Dorothy Thompson

By H illel Levine

In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked His Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews from the Holocaust

By H illel Levine and Lawrence Harmon

The Death of an American Jewish Community : A Tragedy of Good Intentions

By Jan Masaryk

Speaking to My Country

By Susan Quinn

A Mind of Her Own: The Life of Karen Horney

Marie Curie: A Life

B y Vlasta Schnov

Acting in Terezn

By Susan Rubin Suleiman

Budapest Diary: In Search of the Motherbook

By Joseph Wechsberg

The Vienna I Knew: Memories of a European Childhood

By Friderike Zweig

Married to Stefan Zweig

By Stefan Zweig

Adepts in Self-Portraiture: Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy

Amerigo: A Comedy of Errors in History

Balzac

Dostoevsky by Zweig

Freud by Zweig

Joseph Fouch: Portrait of a Politician

Mental Healers : Franz Anton Mesmer, Mary Baker Eddy, Sigmund Freud

The Struggle with the Daemon: Hlderlin, Kleist, Nietzsche

The World of Yesterday

Three Masters: Balzac, Dickens, Dostoevsky

For more information, visit www.plunkettlakepress.com

~ About the author ~

Sebastian Haffner (1907-99) was born in Berlin. He studied law and trained and qualified as a lawyer in Germany in 1933, where he took some divorce cases but mainly worked as a freelance writer until 1938 when he emigrated to England. After the publication of Germany: Jekyll and Hyde, his first book, in 1940, he edited Die Zeitung, the government-supported German-language newspaper in London. In 1942 he joined the Observer for which he wrote leaders and political articles. In 1950 he returned to Berlin as the Observers foreign correspondent, until 1961 when he became a distinguished contributor to the then influential German weekly Stern. Haffner was married and had three children. He died in Berlin.

~ Praise for Germany: Jekyll and Hyde ~

An alarm call trying to awaken the British to the unique nature of Hitler and the Nazi regime... Remarkably prescient J. G. Ballard

Haffners clear-sighted analysis, applied mainly to the dissection of his fellow Germans, annihilates any claim by his contemporaries not to have known about Nazi crimes... Apocryphally, Churchill told his cabinet to read this book so that they would understand the Nazi threat. We should do likewise to understand how close we came to ignoring it Rafael Behr, Observer

A powerful and sustained text... it explodes with rhetorical fireworks. Haffner produces a convincing picture of the Nazis, their numbers, their power and the destructive nihilism that united them Giles MacDonogh, BBC History

~ Contents ~

by Neal Ascherson

Hitler

The Nazi Leaders

The Nazis

The Loyal Population

The Disloyal Population

The Opposition

The migrs

Possibilities

~ Publishers note (2008) ~

This new edition, with an added introduction , reprints the original text, with punctuation lightly emended on some occasions where sense was otherwise obscured.

The subtitle has been added. The notes have been adapted and augmented, with grateful thanks to the staff of the German Historical Institute (London) for their help, from the German edition of the book (translated from the English, as the German original has never been found): Germany Jekyll und Hyde ( Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th. Knaur , Munich, 1996).

~ Introduction ~

by Neal Ascherson

Sebastian Haffner was the most famous German journalist of his generation. And the title of journalist gave him pride. He was not a belles-lettres man, being less fashion-conscious than Joseph Roth and much more worldly and practical than Karl Kraus. He was not a roving reporter whose scoops could undermine empires, like Egon Erwin Kisch, although while working for the Observer in the nineteen fifties he would from time to time leave London and write from some foreign place. He did so with a special blending of vast reflections with the echo of events unfolding around him; a technique known among his Observer colleagues as bombinating from the field.

I am not sure that Haffner ever wrote, in his countless columns, the sort of essay definable in Central Europe as a feuilleton. His pieces were too exclusively political for the classic feuilleton, and were often too deeply angry. Haffners articles were not read by old literati in fur collars, sitting in cafs. They were read by young women throwing back their hair as they smoothed out Stern on a school radiator, or by grave entrepreneurs in first-class compartments, or by bearded men in cellar bars so engrossed in Haffner that their cigarette burned out in the ashtray.

Neither did he, the author of unforgettable studies of Germanys recent past, claim to be a historian. He considered himself a journalist who wrote history. Everything that he wrote had a function, an aim, which was to press a point of view or to achieve some change. Everything that he wrote had a character of public urgency. This was true even of his first political work, Defying Hitler, the memoir which he wrote fresh in exile in 1939 and then abandoned (the manuscript was found by his son and published sixty-one years later, and became an instant best-seller).

In that book, he apostrophized the reader: I will not mind if, after reading the book, you forget all the adventures and incidents that I recount; but I would be pleased if you did not forget the underlying moral.

He never wrote another book about himself, and seems to have wished that he had not written that one. But the urgency, the habit of regarding his writing as didactic, never left him. It was that commanding tone, often witty but always fundamentally serious, which seized his readers and, much later on, his viewers. For some years in the nineteen sixties, Haffner had a weekly evening slot on the third TV channel in West Berlin. Nobody else could have got away with the format. Haffner, eyes twinkling under his huge forehead, would appear on screen and light a cigar. A cloud of smoke then hid everything, until eyes first he emerged and gave the viewers a small, unkind smile. Then, in his high-pitched voice, he began to speak about whatever mattered to him on the political scene. He spoke on until his cigar burned out, and then a final gush of smoke, another smile the screen went black. How often I watched this experience in crowded student cafs which fell silent, entranced, all cigar long!

Next page