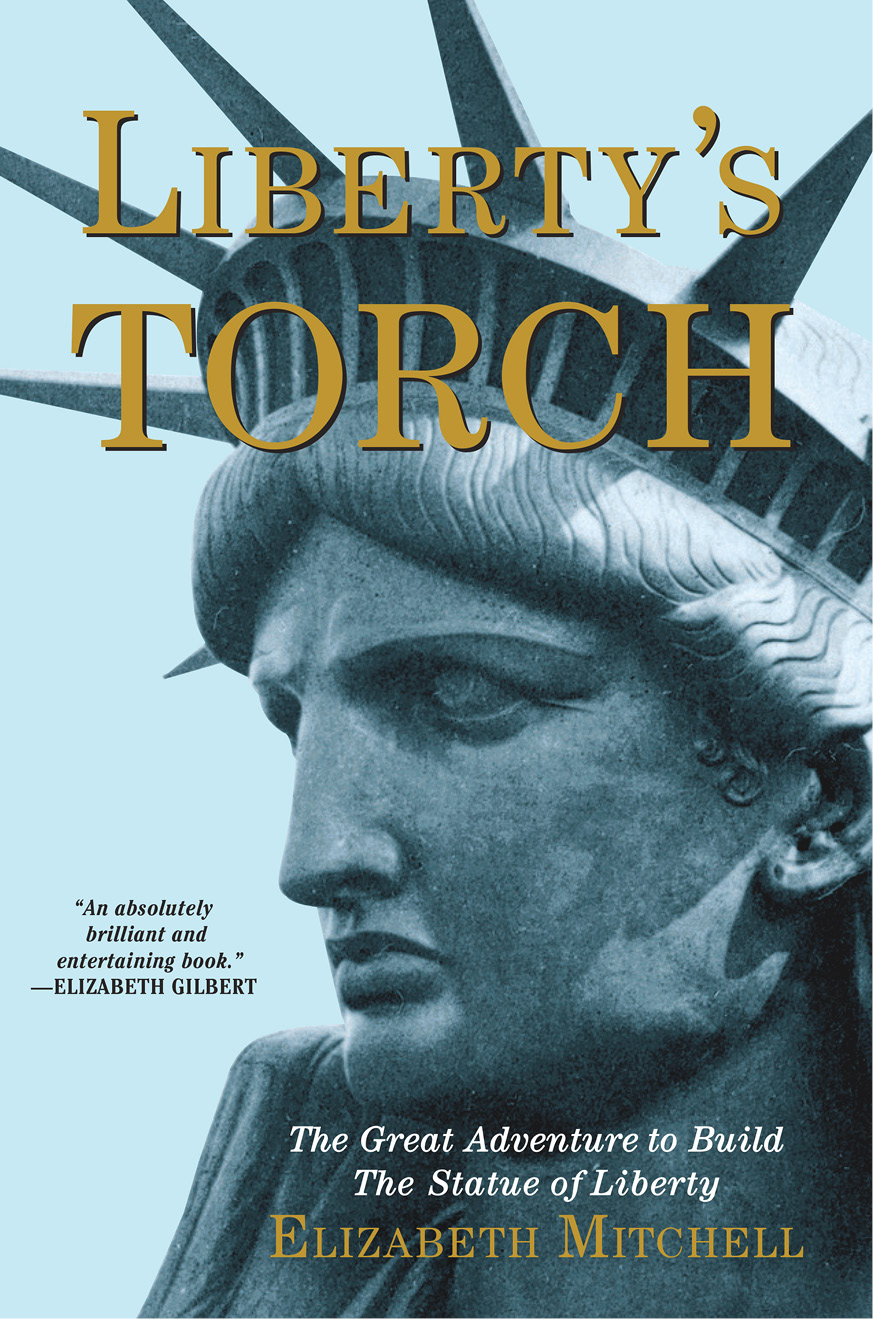

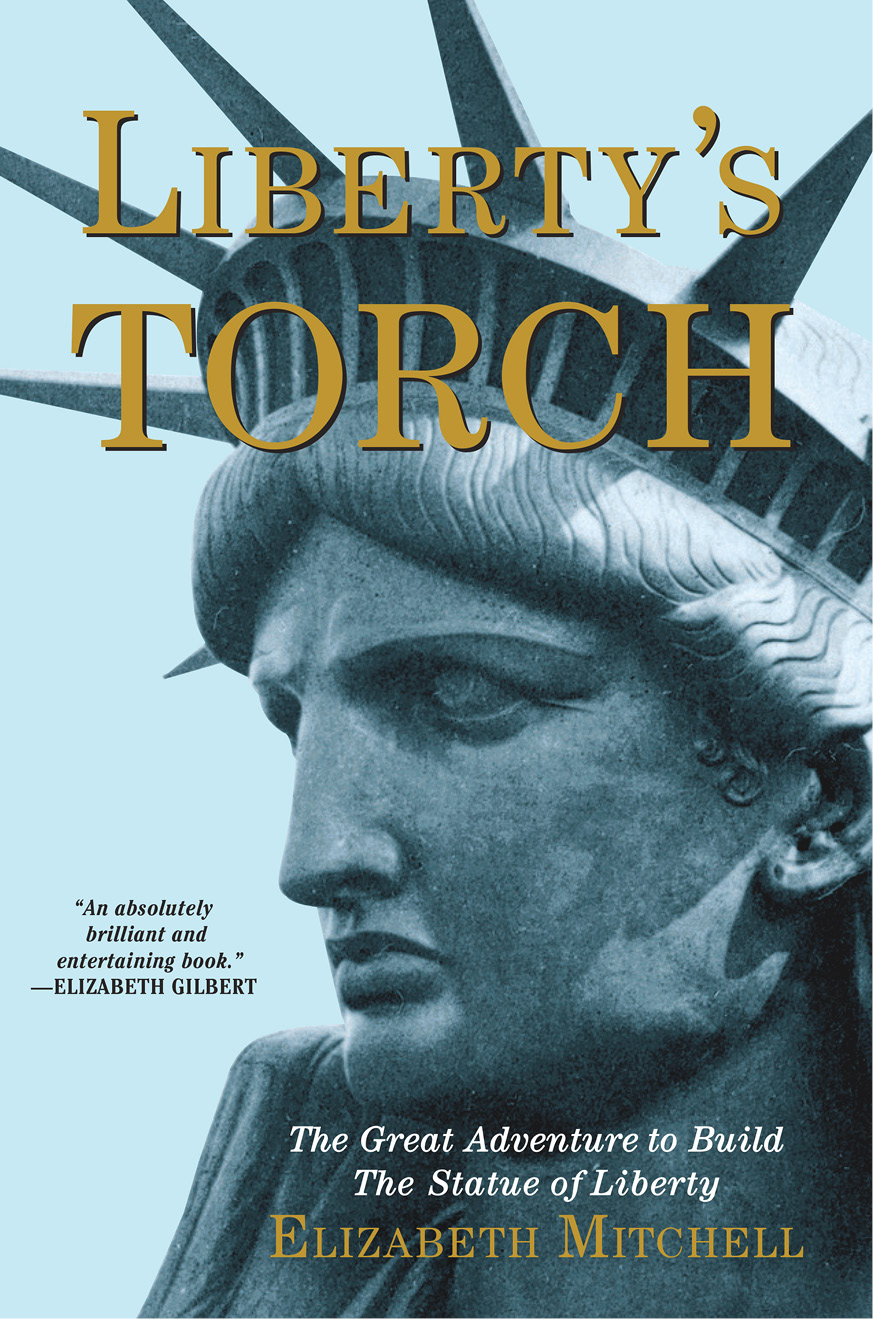

LIBERTYS

TORCH

Also by Elizabeth Mitchell

Three Strides Before the Wire: The Dark and

Beautiful World of Horse Racing

W: Revenge of the Bush Dynasty

LIBERTYS

TORCH

The Great Adventure to Build the Statue of Liberty

Elizabeth Mitchell

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2014 by Elizabeth Mitchell

Jacket design by Christopher Moisan

Jacket photographs: front The Granger Collection, NYC.

All rights reserved. Back Muse Bartholdi, Colmer, reprod. C. Kempf

Portions of this work previously appeared in the Byliner digital single Lady with a Past: A Petulant French Sculptor, His Quest for Immortality, and the Real Story of the Statue of Liberty.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8021-2257-5

eISBN 978-0-8021-9255-4

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

To Lucy and Gigi

Contents

The Idea

The Gamble

The Triumph

Prologue

At three in the morning on Wednesday, June 21, 1871, Frdric Auguste Bartholdi made his way up to the deck of the Pereire, hoping to catch his first glimpse of America. The weather had favored the sculptors voyage from France, and this night proved no exception. A gentle mist covered the ocean as he tried in vain to spot the beam of a lighthouse glowing from the new world.

After eleven days at sea, Bartholdi had grown weary of what he called in a letter to his mother his long sojourn in the world of fish. The Pereire had been eerily empty, with only forty passengers on a ship meant to carry three hundred. He passed his days playing chess and watching the heaving log that measured the ships speed. I practice my English on several Americans who are on board. I learn phrases and walk the deck alone mumbling them, as a parish priest recites his breviary.

These onboard incantations were meant to prepare Bartholdi for the greatest challenge of his career. The thirty-six-year-old artist intended to convince a nation he had never visited before to build a colossus. This was his singular vision, conceived in his own imagination, and designed by his own hand. The largest statue ever built.

The sky turned pink, the Pereire cut farther west through the waves, and before long Bartholdi and his fellow passengers caught the first sight of land and a vast harbor. He described the moment in his letter: A multitude of little sails seemed to skim the water, our fellow travelers pointed out a cloud of smoke at the farther end of a bayand it was New York!

New York was not merely Bartholdis destination; it was his escape. Paris was smoldering. The army had just seized control of the government buildings from the leftist revolutionaries, the Communards. Parisians were upending the streets flagstones, digging into the walkways of the manicured parks to bury an estimated ten thousand corpses from a terrifying rampage dubbed the Bloody Week. A month before that, Bartholdi had left his birthplace in the northeast of France, which had just been turned over to the Prussians after an ill-fated war. He was now officially an exile.

Even in his despair, Bartholdi had been scheming to create an immortal work. His design resuscitated the centerpiece of a deal he almost struck with Egypt three years earlier. He had pitched to Egypts ruler the idea of a colossal statue of a woman, holding up a lantern, to stand in the harbor of the new Suez Canal. The khedive, Ismail Pasha, had turned him down. Bartholdi had been bitterly disappointed but now he intended to build essentially the same figure on Americas shores.

He was not particularly hopeful of success. Each site presents some difficulty, he wrote to his mother. But the greatest difficulty, I believe, will be the American character which is hardly open to things of the imagination.... I believe that the realization of my project will be a matter of luck. I do not intend to attach myself to the project absolutely if its realization is too difficult.

In his belongings Bartholdi carried letters of introduction from prominent intellectuals he socialized with back home. Those letters would earn him entre into the salons, parlors, and offices of powerful people in New York; Washington, D.C.; and other cities. After seventeen years as a professional artist, he knew how to woo such individuals. He cut an appealing figureof moderate height but strong build with intense brown eyes, a Frenchman with the dark coloring of his Italian ancestry. He could be cantankerous but that pique was confined mostly to the pagein his letters to his mother, to whom he was deeply attached; and occasionally in his small leather diaries, which he wrote in a tiny script, using an attached pencil with an ivory head.

The Pereire entered the Narrows and Bartholdi sketched a map of the landforms. He noted the flat shorelines, with only the hills of Staten Island and Long Island to offer variation. Ferryboats two stories tall steamed by, emitting deep-toned blasts... like huge flies. Elegant sailboats glide along the surface of the water like marquises dressed in garments with long trains. He also described the little steamboats, no bigger than ones handbusy, meddling, inquisitive.

His boat landed at Pier 52, just below West Fourteenth Street. The city has a strange appearance, he wrote to his mother. You find yourself forthwith in the midst of a confusion of railroad baggage cars, omnibuses, heavily laden drays, delicate vehicles with wheels like circular spider-webs, the sound of hurrying crowds, neglected cobbled streets, the pavement scarred with railroad tracks, roadways out of repair, telegraph poles on each side of the street, lampposts that are not uniform, signs, wires, halyards of flags hanging down sidewalks encumbered with merchandise, buildings of varying size as in a suburb.

The main avenues he found elegant, cutting north through the tight settlements of lower Manhattan. Broadway extends about eight kilometers in the inhabited part of the city; after that it continues into the country among scattered dwellings.

Coming from Paris, a city recently renovated and beautified by Georges-Eugne Haussmann, Bartholdi found New Yorks chaos shocking. The city had not been planned but rather was cobbled together, with eight-story buildings next to shacks, and trees pushing their roots into the cellars. All of this in a style that is hard to describeAnglo-Marseillais-Gothico-Dorico-Badensis.

He then added pointedly: I shall come back to this in discussing the American character in general.

Bartholdi hastened in his very first days to pitch groups about his proposal, emphasizing the idea that the French and Americans would embark on his colossus project in unison. Those proposals went so badly that six days after his arrival, he reassessed them: Decidedly, I am going to change my tactics.

Next page