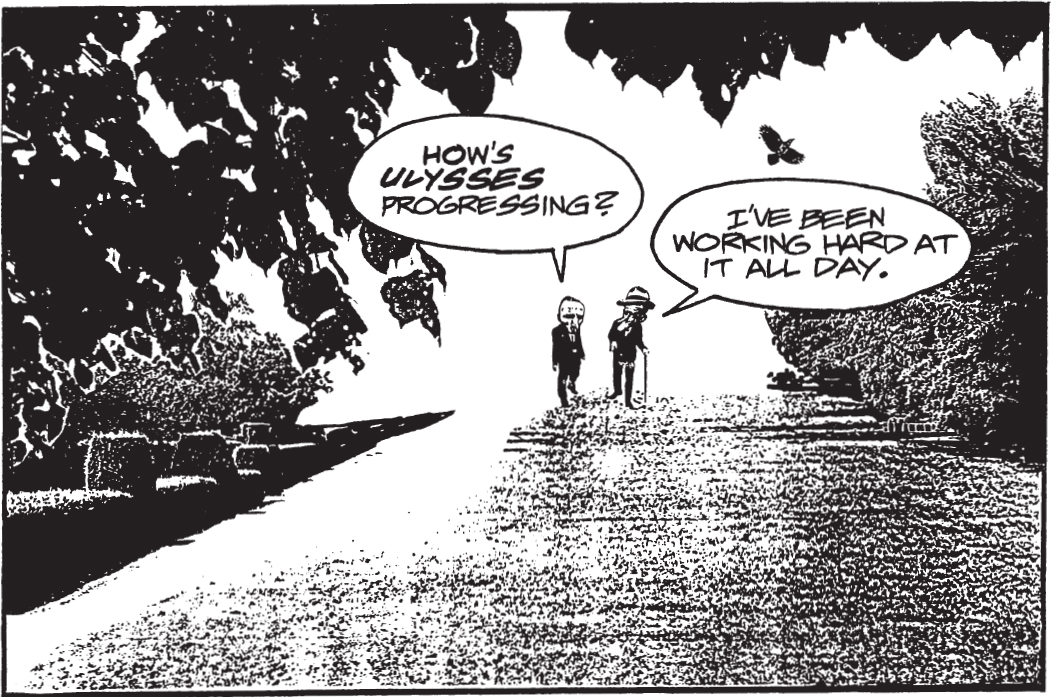

DOES THAT MEAN YOUVE WRITTEN A GREAT DEAL? TWO SENTENCES.

GAWD! TWO SENTENCES? YOU WERE SEEKING THE RIGHT WORDS? NO, I HAVE THE WORDS ALREADY. WHAT I AM SEEKING IS THE PERFECT ORDER OF WORDS IN THE SENTENCE. I THINK I HAVE IT.

Joyce had a musical ear and the sound of prose was always extremely important to him. A golden rule for the reader is when in doubt, read aloud. There is also in Joyce a rich vein of humour, even at the blackest moments. There are plenty of good old-fashioned belly laughs, but also some sly oblique smiles that reward only the careful reader.

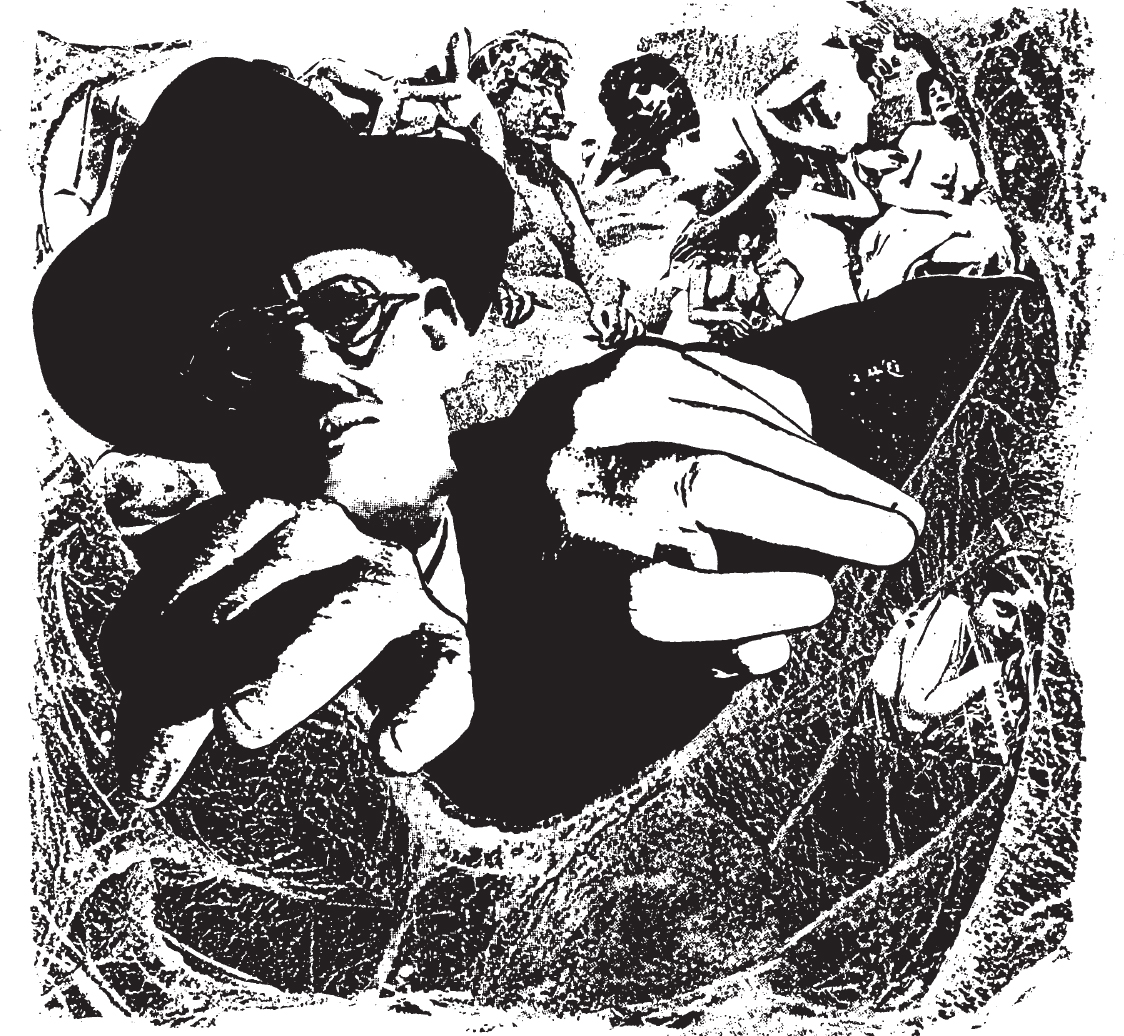

A Rigorous Realist

James Joyce was possessed by an unswerving devotion to his art throughout his life. Undeterred by poverty, illness, family problems or world wars, he never wavered in the service of his often misunderstood genius.

Language was his raw material, and he applied to it the kind of extreme tests and standards more usually expected of poetry. He displayed the same standards of integrity in dealing with his subject matter, an uncompromising realist writing of areas of human experience previously regarded as too mean, too personal, too intimate or too risque to be made the subject of art. In particular, he blew away the cobwebs surrounding the Victorian treatment of sexuality and presented it in an honest manner that was revolutionary. In so doing, he heroically expanded the frontiers of human spiritual development.

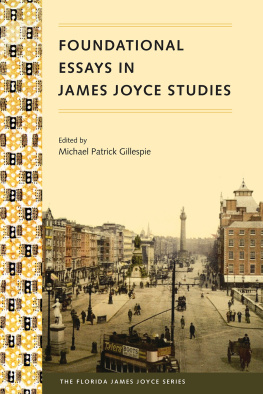

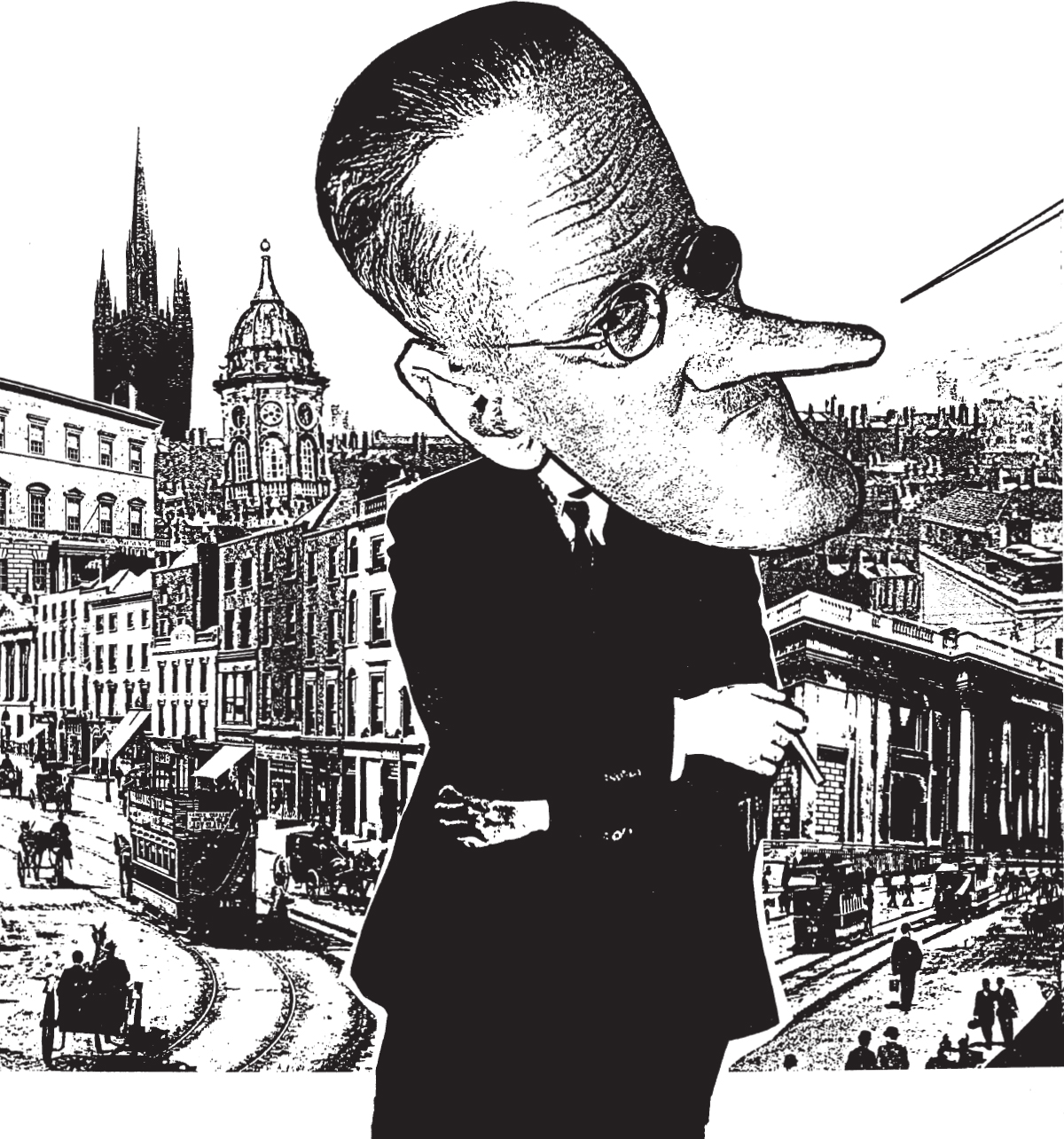

Dublin 1904

Joyce, above all else, is the quintessential modernist recorder of city life.

He first left Dublin in 1904 and did not visit again after 1912. Yet, for the remaining 28 years of his life in exile, he wrote about nothing else but Dublin.

It became for him a city frozen in time the Edwardian Dublin of 1904 with its horse-drawn cabs, gas lamps and British soldiers, a city of some 500,000 souls where respectability and the subversive went hand in hand.

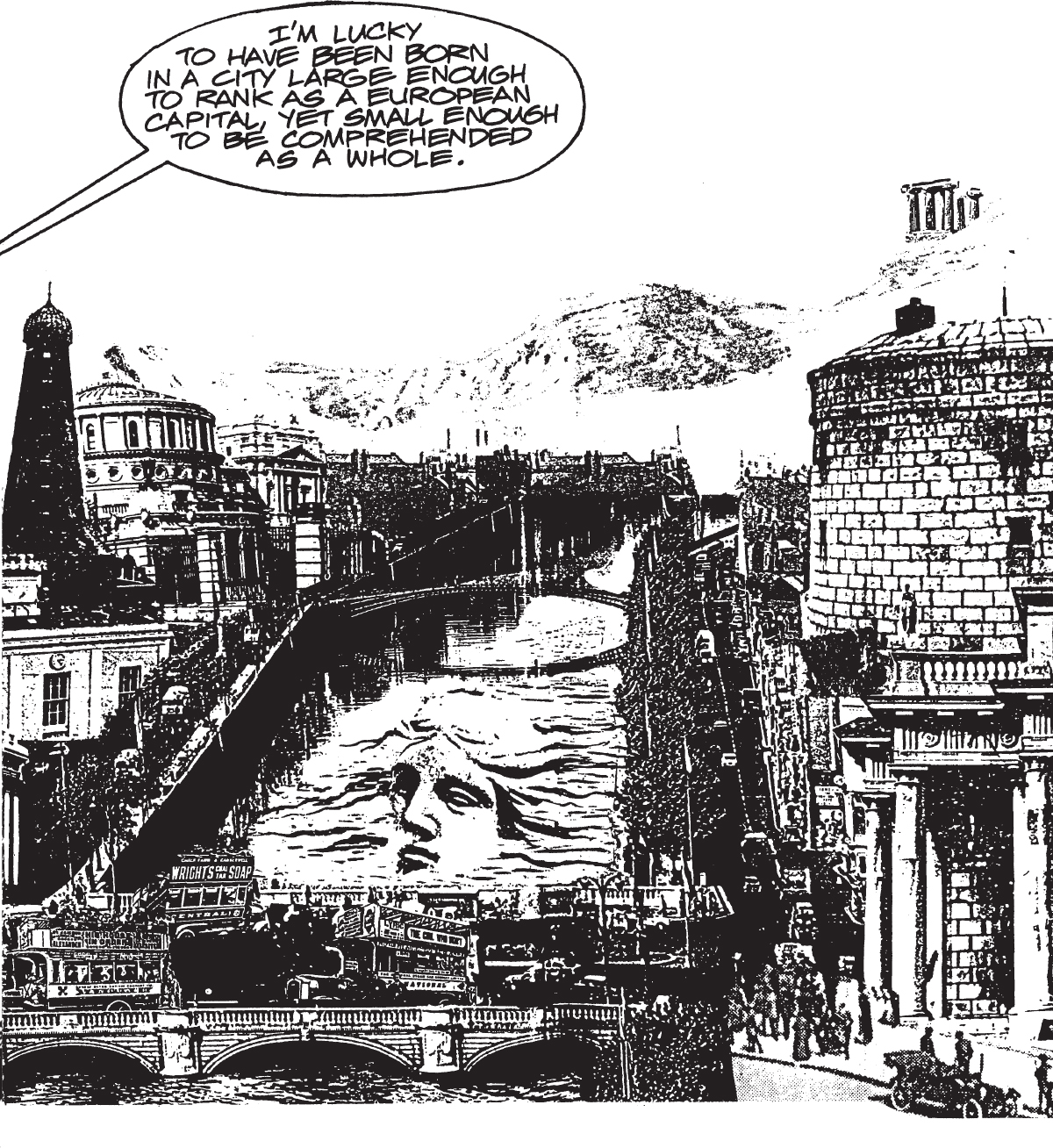

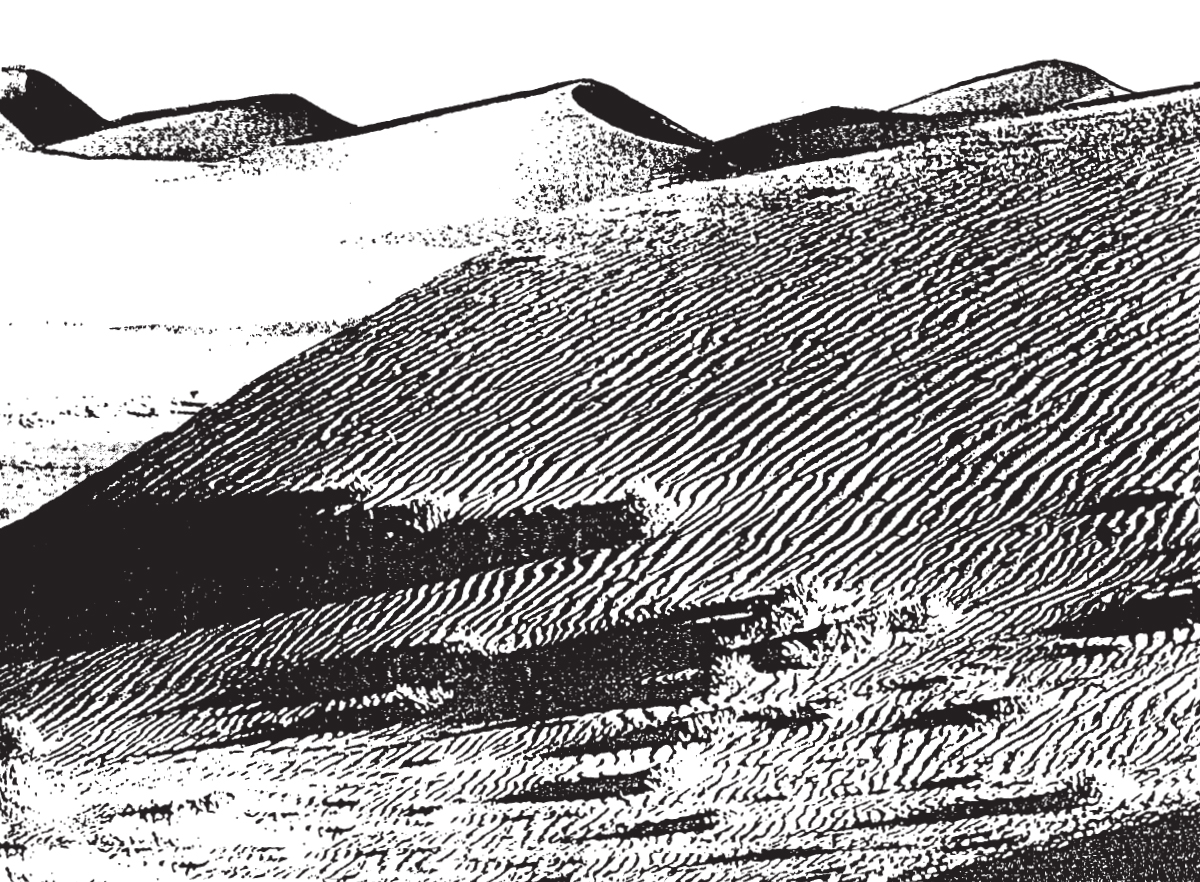

With the Dublin Mountains as a backdrop, the sweep of the bay half circles the metropolis like a sleepers arms, and the River Liffey Joyces Anna Livia rises in the foothills and meanders in a wide arc before flowing through the city to the sea. The Irish name for Dublin is Baile Atha Cliath or the town of the ford of the Hurdles, indicating a convenient place for crossing the river.

IM LUCKY TO HAVE BEEN BORN IN A CITY LARGE ENOUGH TO RANK AS A EUROPEAN CAPITAL, YET SMALL ENOUGH TO BE COMPREHENDED AS A WHOLE.

Dublin was founded by the Vikings over 1,000 years ago (although a settlement of some sort is indicated on Ptolemys map many centuries earlier).

Splendidly brilliant in the 18th century, when for a brief period an independent parliament was established in the capital, Dublins glory did not long survive the extinction of that parliament by the Act of Union in 1800.

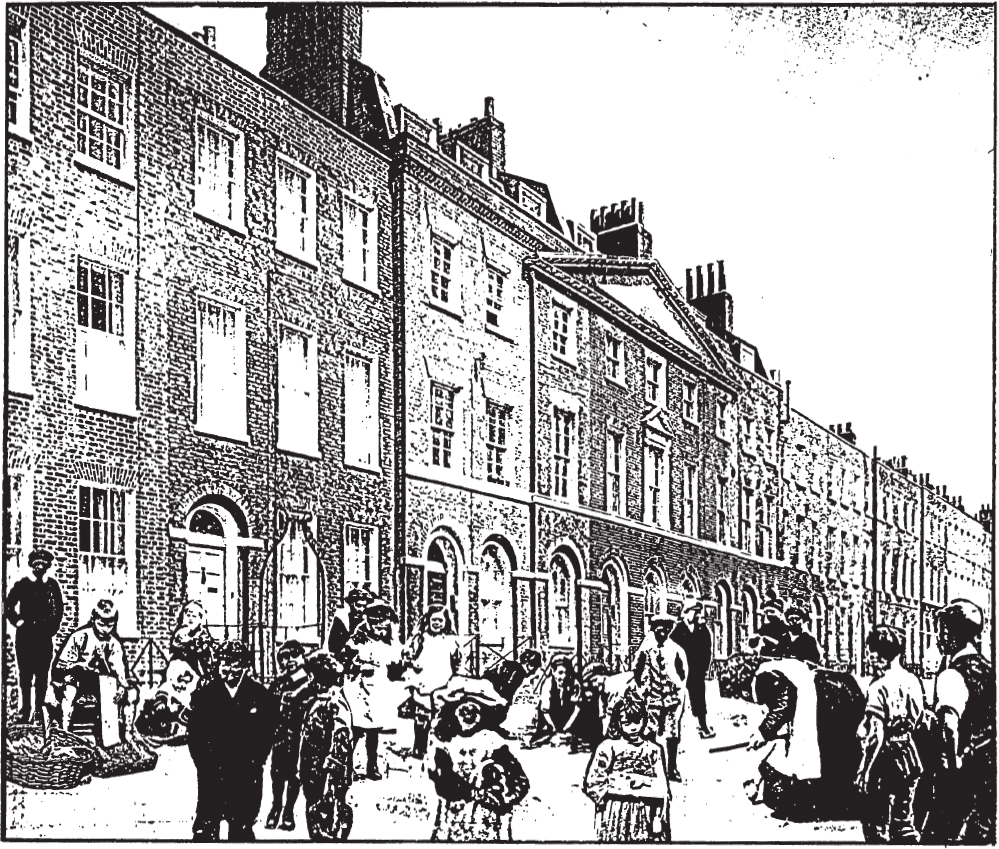

The great town houses of the aristocracy were abandoned, first to the rising Catholic bourgeoisie, and then to tenement occupation.

This is Joyces description of Henrietta Street, which had once been Dublins finest Georgian street.

a horde of grimy children populated the street. They stood or ran in the roadway or crawled up the steps before the gaping doors, or squatted like mice upon the threshold He picked his way deftly through all that minute vermin-like life and under the shadow of the gaunt spectral mansions in which the old nobility of Dublin had roistered.

Dublins old nobility was the arrogant and unrepresentative Protestant lite, far removed from the Gaelic and Catholic Ireland from which James Joyce sprang.

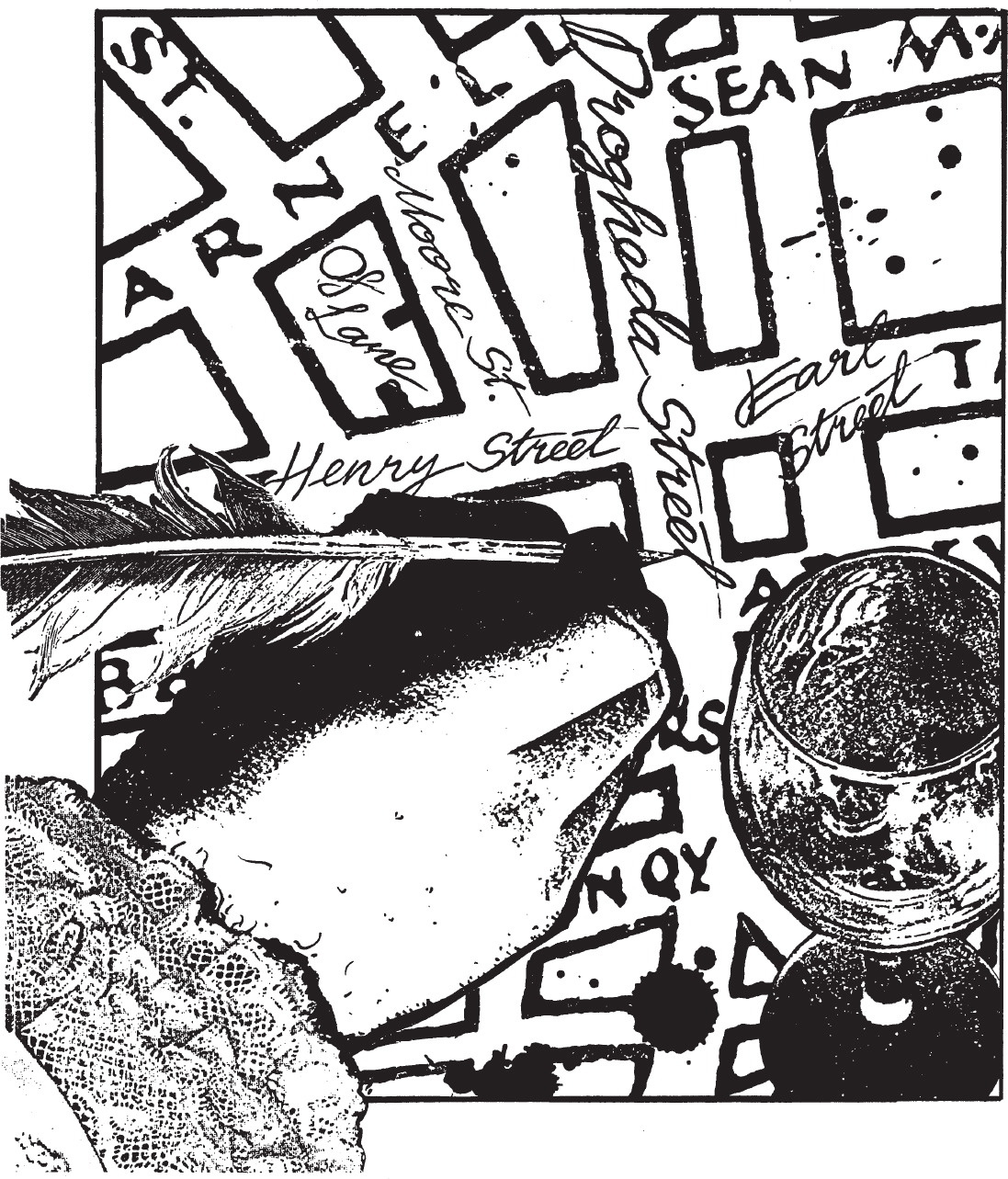

Some idea of the grandiose notions of these past grandees (or so-called Ascendancy) can be seen on the city map. One of the great 18th century landowners, Henry Moore, Earl of Drogheda, literally built his name across the centre of Dublin.

The Dublin Obsession

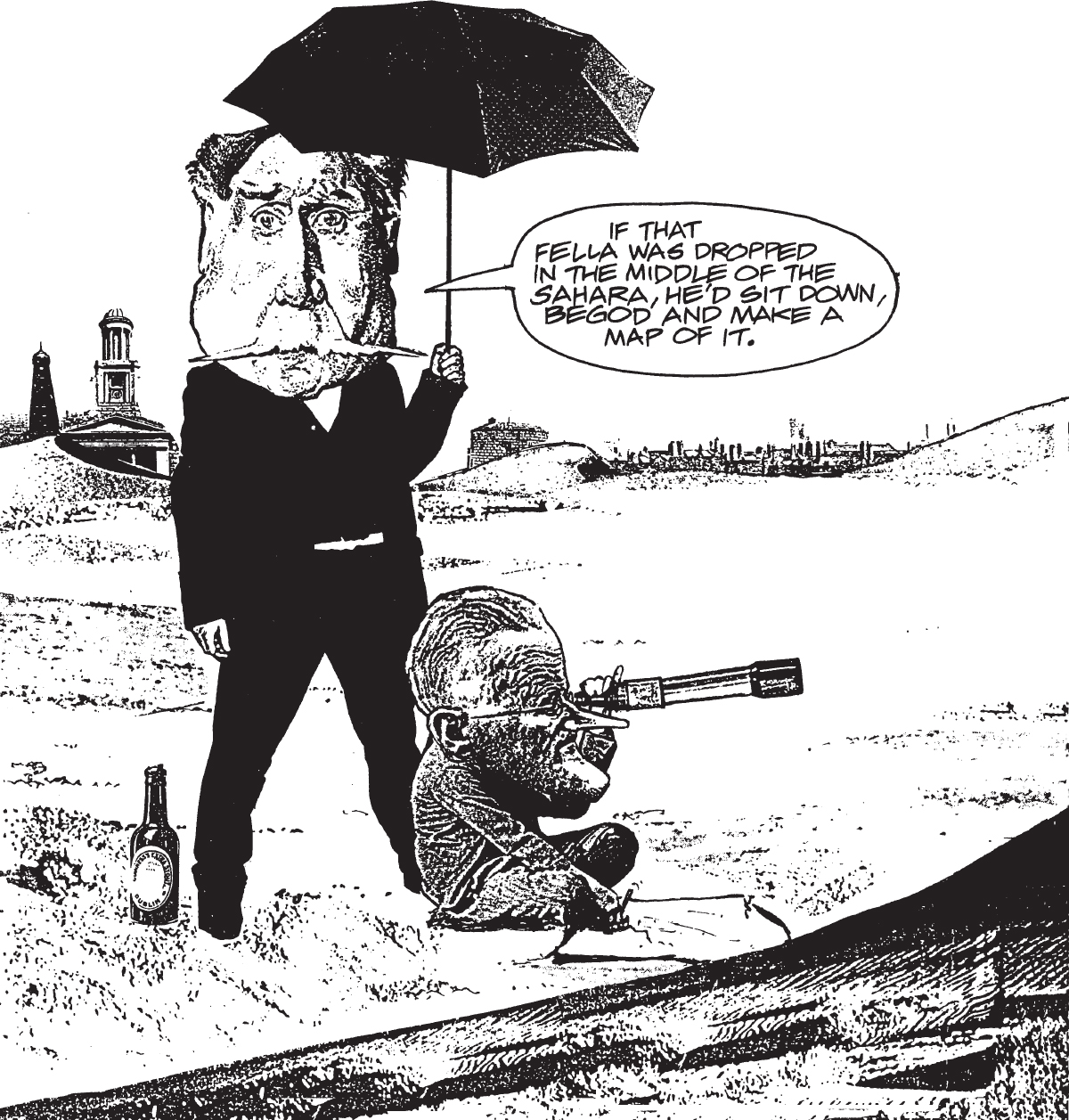

Joyce absorbed much anecdotal information on walks round Dublin with his father John Stanislaus Joyce. There was Buck Whaley the 18th century rake who walked to Jerusalem and played handball on its walls for a bet, and Skin the Goat, accomplice in a sensational political assassination, and Francy Higgins the sham squire These colourful eccentrics were later to flit though the pages of Joyces works.

Even as a child, Joyce had a prodigiously retentive memory and an enquiring mind, as his father remarked.

IF THAT FELLA WAS DROPPED IN THE MIDDLE OF THE SAHARA, HED SIT DOWN, BEGOD AND MAKE A MAP OF IT.

When in middle age Joyce was asked, would he ever return to Dublin? Have I ever left it? he replied. When I die, Dublin will be found engraved upon my heart.

Despite his love for the city, Joyce was ruthlessly unsentimental about it. He told a bemused audience in Trieste before the First World War: Dubliners strictly speaking are my fellow countrymen, but I dont care to speak of our dear dirty Dublin as they do. Dubliners are the most hopeless, useless and inconsistent race of characters I have ever come across on the island or on the continent. This is why this English Parliament is full of the greatest windbags in the world.

Dublins Archivist