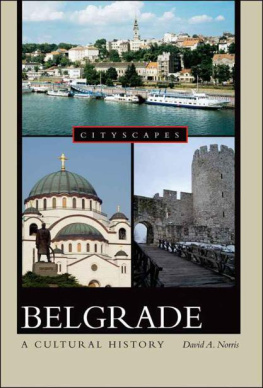

BELGRADE

BELGRADE

A CULTURAL HISTORY

David A. Norris

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2009 by David A. Norris

Foreword 2009 by Svetlana Velmar-Jankovi

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

Co-published in Great Britain by Signal Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Norris, David A.

Belgrade : a cultural history / David A. Norris.

p. cm.(Cityscapes)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780195376081; 9780195376098 (pbk.)

1. Belgrade (Serbia)History. 2. Belgrade (Serbia)Civilization.

3. Belgrade (Serbia)Description and travel. I. Title.

DR2118.N67 2008

949.71dc22 2008025118

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

Contents

Foreword

Belgrade is the gateway to the Balkans. It towers over the place where two great rivers meet, the Sava and the Danube. Over the centuries this meeting point has stood for the geographic and political border between the Balkans and the rest of Europe, between East and West. History tells us that this town, lying in the path of all armies who have tried to break in or out of the Balkans, has been destroyed and rebuilt some forty times in the 2,000 years since Christ.

It was bombed the last time in spring 1999, when the government was in the hands of Slobodan Miloevi, the only remaining communist leader in south-eastern Europe. NATOs air forces carried out the bombardment during a three-month war with the ruling regime, from which the Serbs freed themselves by a peaceful revolution in October of the following year. The foreign traveller visiting Belgrade in 2007 might not notice the traces of that dramatic campaign unless his attention is turned to the buildings waiting for renovationof which not many are left. But he may be interested in the narrative behind the buildings bombed by NATO, which now look like new and have become symbols of Belgrades survival in the period known as the time of transition.

One of these buildings is the slender, green-blue, glass skyscraper which the visitor cannot fail to see whether taking a bus or taxi from the centre of Belgrade, over Branko Bridge on the Sava toward New Belgrade, or from New Belgrade in the opposite direction toward the centre. It stands alone in apparent supremacy over its surroundings near the crossroads of the two boulevards named after the two scientists, Mihailo Pupin and Nikola Tesla. The skyscraper, now in private ownership, is called the Confluence Business Centre and houses the management boards of several large corporations. It used to be, before it was targeted in April 1999, the hub of Slobodan Miloevis political power and party organization, better known as the Building of the Central Committee.

From his windows facing south-east, the august master had a wonderful view over the junction of the two rivers, over the fortress in Kalemegdan Park on the opposite bank of the Sava, sitting on its rocky outcrop above the confluence as it has done for centuries, and over Belgrade, a modern conurbation astride the remains of ancient settlements put here by Celts, Romans, Bulgars, Magyars, Serbs, Turks and Austrians. From his offices looking north-west, he could watch the whole of New Belgrade, the citys most populous borough, where building began only after the Second World War when Josip Broz Tito began his 35year presidency of socialist Yugoslavia. This swarming district has been transformed into interwoven strips of modern architectural and urban structures, tall buildings and broad avenues, piled up without any particular order, attractive in their own way, on the level surface of what was once the low-lying Pannonian plains.

New Belgrade has also been witness to the many social and political changes that have occurred in the city during the last sixty years. It was built slowly, over decades, in the spirit of the anonymous architectural style of Socialist Realism, on land which was mostly sand and mire. It was considered a gloomy dormitory for the many thousands of people who came after the Second World War from the regions to the capital city of the new socialist state to be schooled here, to find work and to stay.

But for some time, and especially since October 2000 when Serbias democratic forces took control of government, those who live here no longer look upon New Belgrade as a dormitoryand with good reason. They now see it as a workshop in which a more modern way of life is being produced, circulated and exchanged in an ever increasing tempo. The transformation has been huge and obvious. Life here teems on the wide and long paths beside the Sava and Danube, on the floating restaurants moored one after the other, especially in the afternoons and evenings. The young and the not-soyoung, from New Belgrade and elsewhere, find their favourite meeting points and places for entertainment. The people of New Belgrade have again fallen in love with their rivers, whose banks were empty in the 1990s as they echoed to the sound of shooting, explosions and violent clashes between different political factions, particularly under the night sky. The cost of flats and commercial property in the area is now rising at a dizzy pace year on year. With its broad boulevards, hotels, Serbian and foreign banks, modern shopping centres, boutiques, restaurants, markets, greenbelt space and avenues of trees, sports halls, private universities and clinics, New Belgrade has suddenly become a very desirable place to work, live, mix and socialize.

In young Belgrade slang, you often hear as a mark of respect for a friends success, Hes living like a king over on New-side! The word Newside in this complimentary phrase means New Belgrade. And yet it also carries an ambiguous subtext about the part of town where money is quickly made and by means which are not always exactly honest. Your own money and your own flat represent an ideal goal for young people in todays Belgrade; not easy to achieve in a world where employment is difficult to find.

Not long ago, a taxi driver, a man in his early thirties, told me of his experience while driving me to the city centre from New Belgrade. He graduated in medicine over five years ago, he said, and then did the usual things: some voluntary work as a doctor and his military service. After a lot of looking around, replying to adverts and waiting, he finally managed to get a job as a doctor in a small town just over a hundred miles from Belgrade and he was very happy. But his happiness did not last long, for less than a year later he had to leave the job he loved. He was not bothered that he had a long daily commute to and from work, nor that he often worked tenor twelve-hour shifts. But he could not reconcile himself to his doctors salary not providing enough for his small family to live on for even ten days in the month. He was forced to make a crucial decision: he left the medical profession for which he had studied eight years, took financial help from his father to buy a new car, and became one of several thousand Belgrade taxi drivers. He was not dissatisfied with his lot, now earning three to four times more than when he was a doctor and with more free time to spend with his family.

Next page