I did not come to NASA to make history.

Sally Ride

Why do we, the solar sails,

fragile as a feathers frond,

silently seek to sail so far?

We walk the air from here to planet out beyond

Because were more than fond of life and what we are.

Ray Bradbury and Jonathan V. Post

To Sail Beyond the Sun

Lily? I suggested, pointing to a name Id scribbled on a damp cocktail napkin. My husband shook his head no. I pressed the pen to my lips and concentrated, trying to balance my pregnant belly while perched on the wobbly edge of a bar stool. It was the summer of 2010, and my husband and I were trying to come up with names for our daughters December arrival. Sitting in a bar in Cambridge, Massachusetts, we brainstormed names, each writing them down privately on a napkin before showing the other, as if we were on some bizarre game show: Name Your Baby! We werent having much luck. We both have unusual first namesNathalia and Larkinso we wanted to find one that wouldnt subject our daughter to a lifetime of odd nicknames. When Larkin wrote down Eleanor, I immediately rejected it. It sounded so old-fashioned. I couldnt imagine naming my daughter that. But as the months went by and my belly grew, the name grew on me too. We started coming up with middle names. I suggested Frances, a fitting tribute to Larkins mother, who had passed away seven years earlier.

Like any modern mother-to-be, I researched the names we were dreaming up on the Internet. When I plugged in Eleanor Frances, I was surprised to find, buried in history, an Eleanor Francis Helin, born November 12, 1932. She was a scientist at NASAs Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in charge of the program that tracked asteroids nearing Earth. Like the scientists we so often see personified in movies such as Armageddon, she hunted the asteroids that get a little too close to home. During her time at NASA, she discovered an impressive number of asteroids and cometsmore than eight hundred. This was the kind of woman I wanted my daughter to share her name with. My search came up with an old black-and-white photo of her, blond bouffant hair curling at her shoulders, a timid smile as she held up an astronomy award for her asteroid discoveries. Exactly how long had this woman worked at NASA? I wondered. Did women even work at NASA as scientists during the 1950s? Unfortunately it looked like I might never find out. Helin had passed away a year before, in 2009. When my daughter was born, in the last hours of December 14, 2010, we named her Eleanor Frances, in part for a woman I had never met but whose story I couldnt stop thinking about.

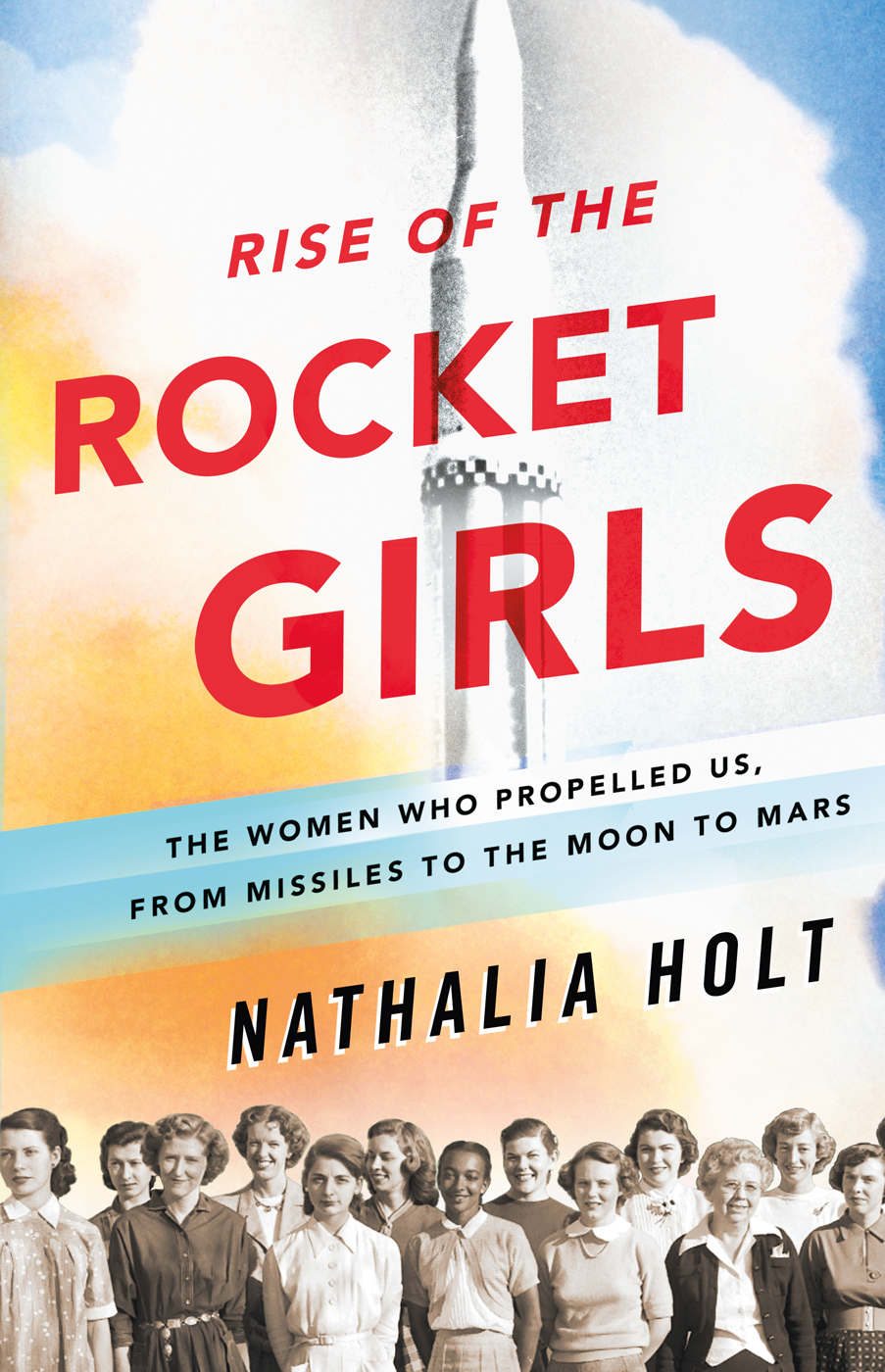

My continued obsession with Eleanor Francis Helin (Glo to her friends) led me to uncover the stories of a group of women intriguingly known as the human computers at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California. These women, recruited in the 1940s and 1950s, were responsible for all the critical calculations at JPL that powered early missiles, rocketed heavy bombers over the Pacific, launched Americas first satellite, guided lunar missions and planetary explorations, and even navigate Mars rovers today. My search unearthed a 1950s picture of the group, the women working at their desks. The image was crisp, yet the archivists at NASA knew only a few of the womens names and werent sure what had become of them. It seemed their stories had been lost in the shuffle of history.

While we tend to think of the role women played during the early years at NASA as secretarial, these women were the antithesis of that assumption. These young female engineers shaped much of our history and the technology we have today. They became the earliest computer programmers at NASA. One of them still works there, the longest-serving woman of the American space program. Their stories give us an inside look at pivotal moments in American history, from a perspective never before told.

Since the cold night my Eleanor Frances was born, Ive thought of these women oftenparticularly when the mood is intense. In my years as a microbiologist, Ive tinkered with broken breast pumps in remote research stations in South Africa, watched my toddler run down darkened laboratory halls, and held in my hands raw data that shimmered with beauty. At each moment, Im brought back to the women who dealt with similar struggles and triumphs a half century ago. How did they handle the sometimes awkward, sometimes wonderful challenges of being a woman, a mother, and a scientist all at once? There was only one way to find out: Id have to ask them.

The young womans heart was pounding. Her palms were sweaty as she gripped the pencil. She quickly scribbled down the numbers coming across the Teletype. She had been awake for more than sixteen hours but felt no fatigue. Instead, the experience seemed to be heightening her senses. Behind her she could sense Richard Feynman, the famous physicist, peeking at her graph paper. He stood looking over her shoulder, occasionally sighing. She knew that her every move was being carefully watched, her calculations closely studied. Her work would inform mission control if the first American satellite would be a success or a crushing failure.

Hours earlier, before the satellite had been launched, her boyfriend had wished her luck. He hadnt quite gotten used to the fact that his girlfriend worked late nights as an integral part of the American space program. Before leaving, he gave her a quick kiss. I love you even if the dang thing falls in the ocean, he said with a smile.