Diana Souhami - Gluck: Her Biography

Here you can read online Diana Souhami - Gluck: Her Biography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Quercus Publishing Plc, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Gluck: Her Biography

- Author:

- Publisher:Quercus Publishing Plc

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gluck: Her Biography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Gluck: Her Biography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Gluck: Her Biography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Gluck: Her Biography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Gluck

Her Biography

Diana Souhami

CONTENTS

I really do want to do some good and lovely work before I die

Gluck in a letter to Nesta Obermer, 1936.

ONE

GLUCK: NO PREFIX, NO QUOTES

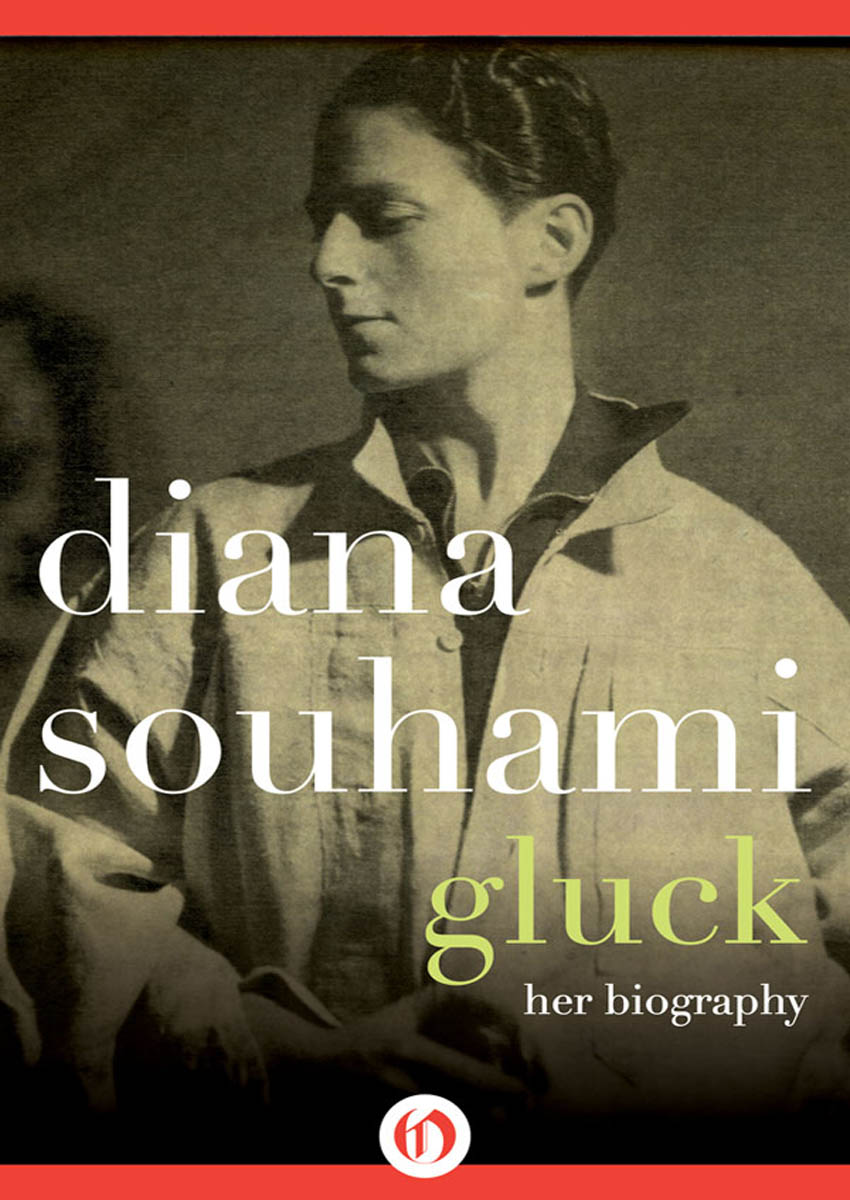

On the backs of photographic prints of her paintings, sent out for publicity purposes, she always wrote in her elegant handwriting: Please return in good condition to Gluck, no prefix, suffix, or quotes. She pronounced her chosen name with a short vowel sound to rhyme with, say, cluck, or duck. She was born Hannah Gluckstein in 1895, into the family that founded the J. Lyons & Co. catering empire, but seldom wanted her wealthy family connections or hated patronymic known.

To Nesta Obermer, her blonde alter ego in Medallion, a painting of their merged profiles, she was Darling Tim, or My bestest darling Timothy Alf, or My Black Brat. Romaine Brooks, twenty years her senior, did a portrait of her in 1924 called Peter a Young English Girl. To one at least of her admirers she was Dearest Rabbitskinsnootchbunsnoo. To Edith Shackleton Heald, the journalist with whom she lived for close on forty years, she was Dearest Grub. To her family she was Hig. To her servants and the tradespeople she was Miss Gluck and to the art world and in her heart she was simply Gluck.

The reason she gave for choosing to be known by this austere monosyllable was that the paintings mattered, not the sex of the painter. She said she thought it sensible to follow the example of artists like Whistler and use a symbol by way of identification. More fundamentally, she had no inclination to conform to societys expectations of womanly behaviour and she wanted to sever herself, but not entirely, from her family.

Gluck she was, and could and did become high-handed and litigious in so being. Many were confused and bewildered as to how to address her with courtesy. She had an irritated exchange with her bank when an unwitting clerk fed her name into the computer as Miss H. Gluck. A graphic designer, faced with the uncomfortable visual dilemma of trying to make GLUCK look comprehensible on the letterhead of stationery for an art society which featured her, along with the Bishop of Chichester and Duncan Grant as its Vice Presidents, stuck in an ameliorating Miss. Gluck resigned and insisted on the inking out of her name. When Weidenfeld & Nicolson published a minor novel which featured an eccentric fictional vagabond called Glck with an umlaut, who lived in a lodging house and painted pictures of defunct clocks and bus tickets, they found themselves besieged with solicitors letters. Gluck regarded any encroachment on her chosen name as trespass liable for prosecution.

Throughout her adult life she dressed in mens clothes, pulled the wine corks and held the door for true ladies to pass first. An acquaintance, seeing her dining alone, remarked that she looked like the ninth Earl, a description which she liked. She had a last for her shoes at John Lobbs the Royal bootmakers, got her shirts from Jermyn Street, had her hair cut at Truefitt gentlemens hairdressers in Old Bond Street, and blew her nose on large linen handkerchiefs monogrammed with a G. In the early decades of this century, when men alone wore the trousers, her appearance made heads turn. Her father, a conservative and conventional man, was utterly dismayed by her outr clobber, her mother referred to a kink in the brain which she hoped would pass, and both were uneasy at going to the theatre in 1918 with Gluck wearing a wide Homburg hat and long blue coat, her hair cut short and a dagger hanging at her belt.

In 1916 when Gluck was breaking from her family home and staying with the Newlyn School of painters in Lamorna, Cornwall, Alfred Munnings sketched her smoking her pipe and dressed as a gypsy. The society photographer E. O. Hopp, who encouraged her to stage her first exhibition in 1924, featured a series of photographs of her, along with Mussolini, Ellen Terry and Bernard Shaw, in The Royal Magazine in December 1926:

I am often asked what I see in the face of my sitters. My answer is: I see what Iseek beauty. Glucks facial contour indicates the qualities expressed in her paintings, combining force and decision with the sensitiveness of the visionary. To look at her face is to understand both her success as an artist and the fact that she dresses as a man. Originality, determination, strength of character and artistic insight are expressed in every line.

He seemed to imply that such qualities are quintessentially masculine. And Gluck regarded peacefulness and mystery as female attributes and strength and genius as male.

In company her appearance and manner were riveting. She was authoritative, had a quality of stillness, a clear voice and no social embarrassment. She liked the discomfort her cross-dressing caused and enjoyed recounting examples of it, like the occasion in the 1930s when she arrived with a theatre party at the Trocadero Restaurant, owned by J. Lyons & Co., to be told no table was free. She pulled rank and gave her family name. Ere, the doorman said, e says shes Miss Gluckstein. Influenced by Constance Spry, with whom she had a close relationship from 19326, she for a time turned androgyny into high fashion. Constance took her to the couturiers Elsa Schiaparelli, Victor Stiebel and Madame Karinska in Paris. They dressed her in pleated culotte, long velvet tunics and Edwardian suits. On holidays with Constance in Tunisia Gluck dressed in a burnous with a geranium behind her ear. In later years, when disappointed in love and at odds with the world, she lost her sartorial flair, bought her pyjamas and jumpers at Marks & Spencer and wore a duffel coat. She was always fastidious though. If she found a crease in her laundered linen painting-smock she sent it back to the kitchen for a maid to iron again.

She did several self-portraits, all of them mannish. There was a jaunty and defiant one in beret and braces stolen in 1981 and another, now in the National Portrait Gallery, which shows her as arrogant and disdainful. She painted it when suffering acutely from the tribulations of love. A couple of others she destroyed when depressed about her life.

She dressed as she did not simply to make her sexual orientation public, though that of course she achieved. By her appearance she set herself apart from society, alone with what she called the ghost of her artistic ambition. And at a stroke she distanced herself from her familys expectations, which were that she should be educated and cultured but pledged to hearth and home. They would have liked her to marry well, which meant a man from a similar Jewish background to hers preferably one of her cousins and to live, as wife and mother, a normal, happy life. By her outr clobber Gluck said no to all that, for who in his right mind would court a woman in a mans suit? Her rebelliousness cut her father to the quick and he thought it a pose. But however provocative her behaviour there was no way he would cease to provide for her, his concept of family loyalty and obligation was too strong.

Courtesy of her private income, she lived in style with staff a housekeeper, cook and maids to look after her. She always kept a studio in Cornwall. In the 1920s and 30s she lived in Bolton House, a large Georgian house in Hampstead village. After the war she settled in Sussex in the Chantry House, Steyning, with Edith Shackleton Heald, journalist, essayist and lover of the poet W. B. Yeats in his twilight years. Both residences had elegantly designed detached studios.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Gluck: Her Biography»

Look at similar books to Gluck: Her Biography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Gluck: Her Biography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.