Daniel Halpern - An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern

Here you can read online Daniel Halpern - An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1970, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:1970

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Daniel Halpern

An Interview With Paul Bowles

DANIEL HALPERN: Why did you first come to Morocco?

PAUL BOWLES: Gertrude Stein suggested it. She had been here three separate summers, staying at the old Villa de France, and she thought I'd like it. She was right. And I still love it. Less, naturally. One loves everything at my age; also it's a little less lovable than it was forty years ago.

HALPERN: What is it that keeps you in Tangier?

BOWLES: It's changed less than the rest of the world, and continues to seem less a part of this particular era than most cities. It's a pocket outside the mainstream. You feel that, very definitely, for a few days or a few weeks, and you come back here, you immediately feel you've left the stream, that nothing is going to happen here.

HALPERN: You were eighteen when you first left America. What lured you to Europe?

BOWLES: Everyone wanted to come to Europe in those days. It was the intellectual and artistic center. Paris specifically seemed to be the center, not just Europe. After all, it was the end of the twenties and just about everybody was in Paris.

HALPERN: Did you know many writers and composers in Paris?

BOWLES: Practically no writers. I met a lot but I didn't know them. Composers? Naturally, Virgil Thomson, and Henri Sauguet and Francis Poulenc. . Not very many, no.

HALPERN: Did you see much of Gertrude Stein while you were there?

BOWLES: I did see a lot of her in 1931. She had read some of the poems I had published, and she didn't like them. I went around in 1931, and I remember she mentioned Bravig Imbs, a poet at that time who wrote for various magazines, and she said, "Yes, Bravig Imbs is a very bad poet, but you're not a poet at all." She also had things to say about my music. I played her my music in 1931 and she said, "It's interesting." And then I went back in 1932 to her country house in Belignin and played some newer music for her, and she said, "Ah, last year your music wasn't attenuated enough, and this year it's too attenuated." That's all she had to say. Except that she told me to go to Tangier. She was liking me at the time, which meant that I could trust her recommendation. The next year, when she was not liking me at all, she suggested I go to Mexico, adding after a pause, "You'd last about two days."

HALPERN: Was she in favor of your giving up writing and devoting more time to your music?

BOWLES: I suspect she thought I had no ability to write. I remember we were sitting in the garden at Bilignin and she said, "I told you last week what was the matter with your poetry. What have you done with it since then, with those particular poems? Have you rewritten them?" And I said, "No, of course not; they've already been published that way. How could I rewrite them?" And she said, "You see! I told you you were not a poet. A real poet would have gone up and worked on them and then brought them down and showed them to me a week later, and you've done nothing whatever."

HALPERN: What was it about writing that made you put composing aside?

BOWLES: I'm not sure. I think it had a lot to do with the fact that I couldn't make a living as a composer without remaining all the time in New York. I was very much fed up with being in New York.

HALPERN: When did you begin to write?

BOWLES: At four. I have a whole collection of stories about animals that I wrote then.

HALPERN: But it was as a poet that you first published, in transition?

BOWLES: I had written a lot of poetry (I was in high school) and had been buying transition regularly since it started publishing. It seemed to me that I could write for them as well as anyone else, so I sent them things and they accepted them. I was sixteen when I wrote the poem they first accepted, seventeen when they published it. I went on for several years as a so-called poet.

HALPERN: What ended your short career as a poet?

BOWLES: I think Gertrude Stein had a lot to do with it. She convinced me that I ought not to be writing poetry, since I wasn't a poet at all, as I just said. And I believed her thoroughly, and I still believe her. She was quite right. I would have stopped anyway, probably.

HALPERN: Were there any important early literary influences?

BOWLES: Well, I suppose everything influences you. I remember my mother used to read me Edgar Allan Poe's short stories before I went to sleep at night. After I got into bed she would read me Tales of Mystery and Imagination. It wasn't very good for sleepingthey gave me nightmares. Maybe that's what she wanted, who knows? Certainly what you read during your teens influences you enormously. During my early teens I was very fond of Arthur Machen and Walter de la Mare. The school of mystical whimsy. And then I found Thomas Mann, and fell into The Magic Mountain when I was sixteen, and that was certainly a big influence. Probably that was the book that influenced me more than any other before I went to Europe.

HALPERN: Before you actually begin writing a novel or story, what takes place in your mind? Do you outline the plot, say, in visual terms?

BOWLES: Every work suggests its own method. Each novel's been done differently, under different circumstances and using different methods. I got the idea for The Sheltering Sky riding on a Fifth Avenue bus one day going uptown from Tenth Street. I decided just which point of view I would take. It would be a work in which the narrator was omniscient. I would write it consciously up to a certain point, and after that let it take its own course. You remember there's a little Kafka quote at the beginning of the third section: "From a certain point onward there is no longer any turning back; that is the point that must be reached." This seemed important to me, and when I got to that point, beyond which there was no turning back, I decided to use a surrealistic techniquesimply writing without any thought of what I had already written, or awareness of what I was writing, or intention as to what I was going to write next, or how it was going to finish. And I did that.

HALPERN: What about your second novel, Let It Come Down?

BOWLES: That was altogether different. I began to write that on a freighter as I went past Tangier one night. I was on my way from Antwerp to Colombo, in Ceylon, and we went past Tangier and I felt very nostalgicI could see faint lights in the fog and I knew that was Tangier. I wanted very much to stop in and see it, but not being able to, since the boat went right on past, I created my own Tangier. I started by imagining that I was standing on the cliff looking out at the place where I was on the ship. I transported myself from the ship straight over to the cliffs and began there. That was the first part I wrote. I worked backward and forward, as it were, from that original scene.

HALPERN: Where Dyar and Hadija stand on the top of a cliff and see freighters going by.

BOWLES: That's right. Then on the ship, before I got to Colombo, I worked it outthe sequence of events, the patterns of motivations, the juxtapositions. Again I decided to use exactly the same writing technique I had used with The Sheltering Sky. To get it up to a place from which it could roll of its own momentum to a stationary point, and then let go and use the automatic process. It's quite clear where it happens. It's on the boat trip.

HALPERN: When you wrote the scene in which Dyar was high on majoun, the evening he had dinner with Daisy, were you yourself under the influence of kif?

BOWLES: No. The whole book was written in cold blood, up to that point. But for the last section of the book I went up to Xauen and stayed in the hotel there for about six weeks, writing only at night after dinner. After I had worked for half or three quarters of an hour, and it was going along, I would smoke. That made it possible for me to write four or five hours rather than only two, which is all I can usually do. The kif gave me a much longer breath.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

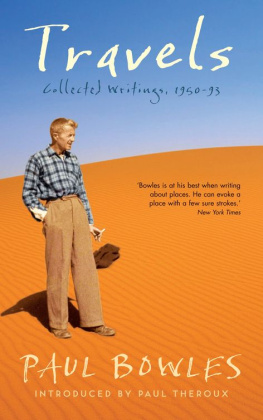

Similar books «An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern»

Look at similar books to An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book An Interview With Paul Bowles by Daniel Halpern and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.