PAUL THEROUX

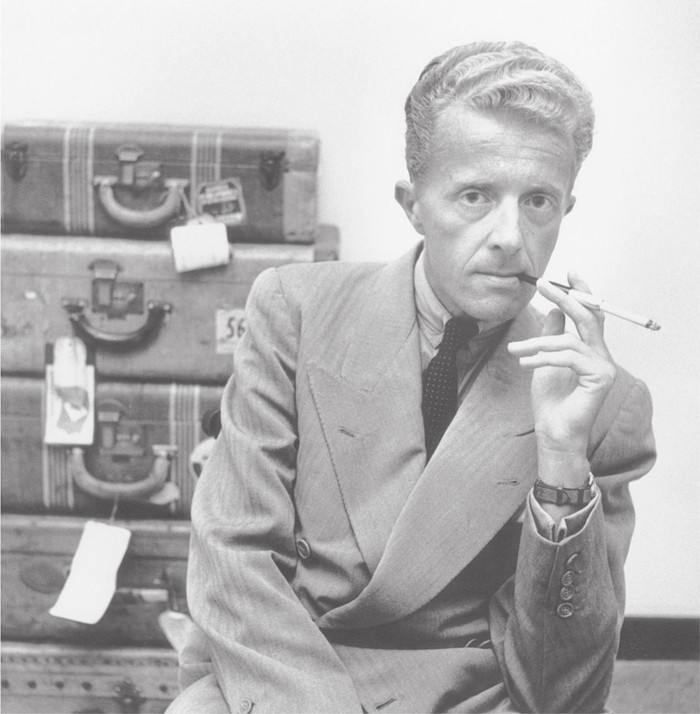

P aul Bowles of the stereotype is the golden man, the enigmatic exile, elegantly dressed, a cigarette holder between his fingers, luxuriating in the Moroccan sunshine, living on remittances, occasionally offering his alarming and highly polished fictions to the wider world. This portrait has a grain of truth, but there is much more to know. Certainly, Bowles had style, and a success with one book. But a single book, even a popular one, seldom guarantees a regular income. And, quite apart from money, Bowles life was complicated emotionally, sexually, geographically, and without a doubt creatively.

A resourceful man as the exile or expatriate tends to be Bowles had many outlets for his imagination. He made a name for himself as a composer, writing the music for a number of films and stage-plays. He was a music ethnologist, an early recorder of traditional songs and melodies in remote villages in Morocco and Mexico. He wrote novels and short-stories. He wrote poems. He translated novels and poems from Spanish, French and Arabic, and created more than a dozen books with the Moroccan storyteller Mohammed Mrabet. So the louche languid soul of the stereotype turns out to have been a very busy man, highly productive, verging on a drudge.

He wrote travel essays, too, a whole book of them, which appeared as Their Heads are Green and Their Hands are Blue (1963). And as this new and valuable collection shows, he wrote vastly more travel pieces than are represented there, more than 30 of them that have never been collected before or reprinted. These range from journal entries and near prose-poems, a long autobiographical poem (Paul Bowles, His Life), polemical essays, political commentaries, and magazine pieces for glossy travel magazines, as well as magisterial introductions to books, such as I am attempting to do now.

He was handsome and hard to impress, watchful, solitary, and knew his own mind, his mood of acceptance, even of fatalism, made him an ideal traveler. He was not much of a gastronome as his fiction shows, the disgusting meal (fur in the rabbit stew) interested him much more than haute cuisine. He was passionate about landscape and its effects on the traveler, as The Baptism of Solitude demonstrated, he was fascinated by the moods of the sky; and he was animated by the grotesque, wherever its misshapen form can be found. (He would have loved this observation by Augustus Hare in The Story of My Life: It used to be said that the reason why Mrs. Barbara had only one arm and part of another was that Aunt Caroline had eaten the rest.) Contemptuous of what passes for progress or technology, he speaks in one of these pieces about Colombo being afflicted with the Twentieth Centurys gangrene , by which he means modernity.

As these newly disinterred pieces show over and over, Bowles was far from the dandy-dilettante that he is sometimes perceived to be. In the 62 years they represent, from 1931 to 1993, Bowles was a serious and extremely hard-working writer, trying to make a living; for, after the success of The Sheltering Sky (1948), his books were not brisk sellers. This is a salutary as well as an enlightening collection, demonstrating that the prudent writer, if he or she wishes to be spared the indignities of a real job, and the oppressions of a tetchy boss, has to keep writing. Bowles was fortunate in writing at a time (not long ago, but now gone) when travel magazines still welcomed long thoughtful essays. He wrote for the American Holiday magazine. The frivolous name masked a serious literary mission. The English fiction writers, V S Pritchett and Lawrence Durrell also traveled for this magazine; so did John Steinbeck after he won the Nobel Prize for literature, when he crisscrossed the United States with his dog. Bowles wrote for The Nation and Harpers too, and contributed to essay collections. As we see here, Bowles wrote a piece for Holiday about hashish, another of his enthusiasms, since he was a life-long stoner.

He knew what he enjoyed in travel, and what bored him: If I am faced with the decision of choosing between visiting a circus and a cathedral, a caf and a public monument, or a fiesta and a museum, I am afraid I shall normally take the circus, the caf, and the fiesta.

No matter who he is writing for travel magazine or pompous quarterly he is never less than felicitous, and often funny. Of the Algerian hinterland: When you come upon a town in such regions, lying like the remains of a picnic lunch in the middle of an endless parking lot, you know it was the French who put it there. Or in the desert, drinking piping hot Pepsi Cola, or seeing locust ravaged date palms whose branches look like the ribs of a broken umbrella, or the unforgettable Monsieur Omar, lying in his bed smoking, clad in only his shorts, a delighted and indestructible Humpty Dumpty.