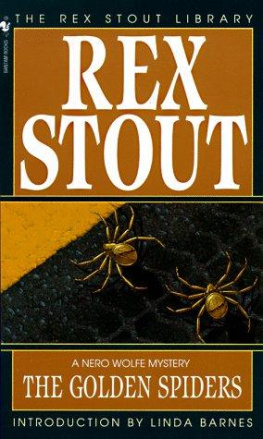

The likeness of those who choose other patrons than Allah is as the likeness of the spider when she taketh unto herself a house, and lo! the frailest of all houses is the spiders house, if they but knew.

Ten or twelve years ago there came to live in Tangier a man who would have done better to stay away. This wickedly portentous sentence, which begins Paul Bowless story The Eye, couldwith the medieval city of Fez substituted for the cosmopolitan port of Tangierjust as easily serve as the opening of The Spiders House and for most of Bowless novels and stories, especially if we expand the list of ill-advised travel destinations to include nearly all of Morocco and a virtual Baedeker of hellish jungle outposts in Latin America and Asia. For Bowless obsessive subject, to which he returned again and again, and which he wrote about brilliantly, was the tragic and even fatal mistakes that Westerners so commonly make in their misguided and often presumptuous encounters with the mysteries of a foreign culture.

One can hardly imagine a more timely theme, one more perfectly suited to the perilous new world in which we find ourselves. Yet, strangely, Paul Bowless name never (as far as I know) appeared on those rosters of writers one saw mentioned in the aftermath of September 11, classic authors whose work appears to speak across centuries and decades, directly and helpfully addressing the crises and drastically altered realities of the present moment: terrorism, violence, neocolonialist warfare, revolution, and our dawning awareness of the hidden costs of colonialism and globalization. Perhaps its because the books that were commonly cited (War and Peace, The Possessed, The Secret Agent, and so forth) seemed, even at their most pessimistic, to offer some hope of redemption, some persuasive evidence of human resilience and nobility; whereas Bowless fiction is the last place you would go for hope, or for even faint reassurance that the world is anything but a horror show, a barbaric Darwinian battlefield.

Frequently, Bowles begins his fiction in ways that seem to promise (or threaten) the sort of narrative we might expect from other writers who have focused on the confrontation between East and West, from novelists as dissimilar as Conrad, Naipaul, and Forster, from works in which a naive colonial sightsees his way into one heart of darkness or anotherand lives to regret it.

So The Spiders House starts off with a prologue that could almost (but not quite) pass for the introduction to an unusually well written political thriller. John Stenham, a writer who has been living in Fez for a very long time, an American who speaks Arabic, who loves the culture with a passion bordering on the delusional, and who understands the locals as well as any Westerner canwhich is to say, not at allis being escorted home from a dinner party. His Moroccan hosts have insisted that the streets are unsafe for him to walk alone, and though Stenham resists with the insulted bravado of the foreigner who has proudly gone native, he accedes because the mood of the city has lately seemed restive and strange. Ever since that day a year ago when the French, more irresponsible than usual, had deposed the Sultan, the tension had been there, and he had known it was there. But it was a political thing, and politics exist only on paper; certainly the politics of 1954 had no true connection with the mysterious medieval city he knew and loved. Already, the sentient reader will have predicted that this political thing will affect Stenham more than he could have predicted or imagined, and that the shock of his highly unpleasant awakening will give the novel the sort of arc we might find in a book by, say, Graham Greene.

But almost immediately we can watch Bowles part company with his fellow authors and enter territory that he has claimed as uniquely his own, a universe that few, if any, of us would willingly choose to inhabitwhich is not to say that Bowless lifelong residence in that bleak and harsh (though often grimly hilarious) landscape seems voluntary, exactly.

The next long section is written from the point of view of a Moroccan boy named Amar, a complex, intelligent, and intuitive kid from a poor and pious family who, despite his own sharp instincts and good judgment, gets pulled into the very heart of the political thing that Stenham would so love to avoid and ignore. Its a convincing and daring portraitnotably few European or American writers have had the courage to write from the perspective of a North African Muslim boyand one that is absolutely necessary for Bowless narrative strategy. Because Amars experience and his view of politics, of religion, of the nature of human existence, and of the way in which the universe operates could hardly be more unlike Stenhams ideas or those of Stenhams chic, decadent American and British friends. This profound and unbridgeable difference creates a tension that underliesand spikesthe pressure created by the thickening web of conspiracy, and by the growing discord and bloody violence erupting in the souks and streets of Fez.

In his characteristically distanced, clinical, quietly confident and authoritative tone, employing a rigorously unadorned, quasi-journalistic prose style, Bowles approaches his material and his characters in a way that seems relentlessly anthropological, scientific, distanced, unbiased by either contempt and derision on the one hand or sympathy and affection on the otheror by any powerful or particular tribal loyalties of his own. Writing about expatriates and Moroccans warily coexisting in the crowded cities and desert encampments of North Africa, he depicts all these groups acting badly. Even the unusually appealing Amar turns out to be capable of committing murder (manslaughter, really) without suffering much remorse. Every community seems capable of carrying out any crime, no matter how mindless or vilewilling and able to do anything except understand one another.

What mostly (if not entirely) exempts Bowles from the charges of racism that his portrayals of brutal Moroccans have, at times, occasioned is the fact that his dispatches from the various frontiers of savagery are so evenhanded and inclusive. Its not at all clear that the vengeful merchants in his story The Delicate Prey or the sadistic bandit tribe in A Distant Episode are any worse than the Frenchmen in The Spiders House, who round up all the young males in the medina of Fez and bring them into the police station to be tortured and perhaps killed. As far as I can see, said Bowles in a 1981 Paris Review interview, People from all corners of the earth have an unlimited potential for violence.

Readers accustomed to parsing literature for clues to the personal history of a writer, or for instruction on how to live, may be puzzled by the discrepancies between a body of work that seems to advise against ever leaving home and the facts of Bowless peripatetic existence. An avid and intrepid traveler, Paul (a dentists son from Queens) abandoned a promising career as a composer and spent much of his early adulthood in Paris and Germany, North Africa, Mexico, Guatemala, Ceylon, and Thailand. From the 1940s until his death in 1999, he was a more or less permanent resident of Tangier, where he lived with his famously eccentric and fascinating wife, Jane, author of the dazzlingly original novel