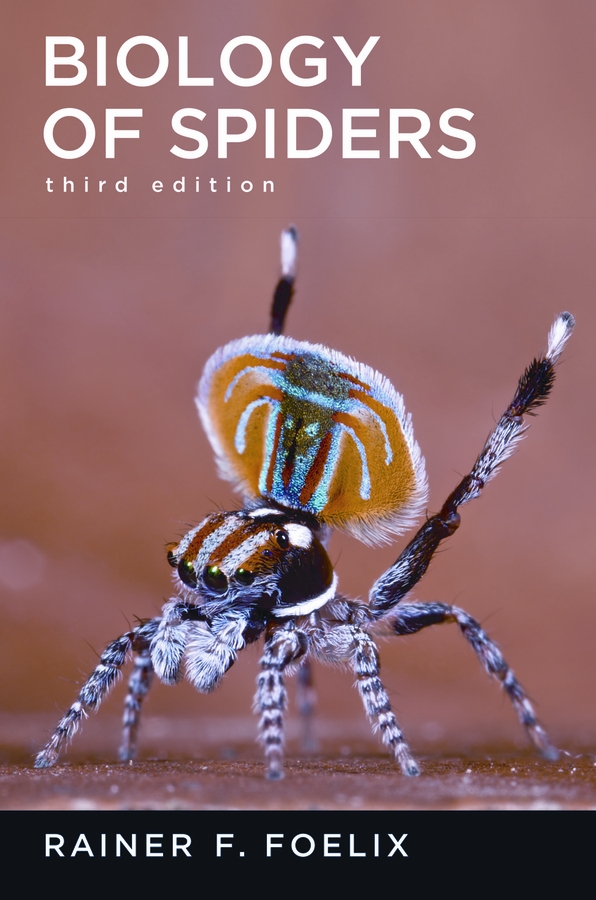

Biology of

SPIDERS

It is hoped that the reader approaches the subject of spiders with as much curiosity as this cat in this Japanese silk painting. Curiosity does not necessarily kill the catnor the spider. (Cat and Spider by Oide Makoto, 18361905; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.)

RAINER F. FOELIX

Biology of

SPIDERS

Third Edition

2011

Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2011 by Oxford University Press

The copyrights for the first and second editions of Biology of Spiders have been

with Georg Thieme Verlag KG, Stuttgart, Germany 1979, 1992, and were

transferred to the author in 2009.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Foelix, Rainer F., 1943

[Biologie der Spinnen. English]

Biology of spiders / Rainer F. Foelix. 3rd ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-19-973482-5 (pbk.) 1. Spiders. I. Title.

QL458.4.F6313 2010

595.44dc22 2010009511

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

It is now exactly 30 years that Biology of Spiders was first published, and I never expected nor planned to follow up with any further editions. When the science editor of Oxford University Press asked me last year whether I would prepare a third edition, I had at first strong reservations because I knew vaguely how much work would be in stock for me: 12 years had passed since the second edition, and literally thousands of articles about spiders had been published during that time. I took up the challenge anyway and subsequently spent an entire year working exclusively on this new edition. Going through the enormous amount of spider literature was only possible through the internet, rapid information exchange by e-mail, and the support of kind colleagues who sent me with their latest spider publications. Including the major results of arachnological research of the past decade, it was thus possible to update all ten chapters. This is not to say that it is a complete revisionof course, there will be omissions, deliberate and unconscious ones. My goal was always to provide a readable book on the biology of spiders, not an encyclopedia. The fact that this new edition nevertheless contains more than 500 new references gives some idea of how much of the recent literature has been incorporated.

Particular attention was paid to the illustrations. Since all the former drawings and photographs had to be scanned anew, this provided a good opportunity to improve and to correct any flaws in the 200 illustrations of the last edition. Almost 100 new pictures have been added to the present edition, often originals that were taken specifically for this book. Many unique photographs were contributed by fellow arachnologists, to whom I am most grateful.

My thanks go to the following colleagues for their help and support: Friedrich Barth, Jon Coddington, Paula Cushing, Bill Eberhard, Bruno Erb, Cheryl Hayashi, David Hill, Martin Huber, Yael Lubin, Peter Michalik, Wolfgang Nentwig, Martin Nyffeler, Brent Opell, Bastian Rast, Robert Raven, Jerome Rovner, David Schrch, Karin Schtt, Paul Selden, Robert Suter, Rolf Thieleczek, George Uetz, Benno Wullschleger, and Samuel Zschokke. I also wish to express my gratitude to the following institutions: The Naturama Aargau for use of their computer and graphics facilities, the Neue Kantonsschule Aarau for letting me work on their electron microscopes, and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, for allowing access to the scientific literature. Finally, Id like to thank my editor Phyllis Cohen and her colleagues Lisa Stallings, Karla Pace, and Jennifer Kowing at Oxford University Press and Anindita Sengupta at Glyph International for transforming my manuscript into an attractive book.

R. F. F.

Aarau

January 2010

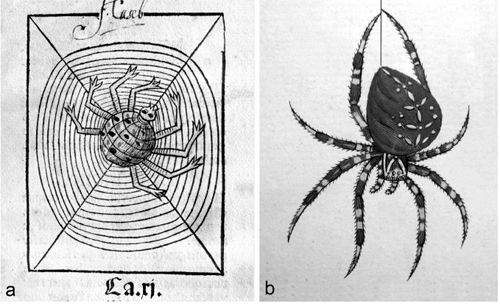

Most people dislike spiders. And, usually, they know very little about them. This lack of knowledge is also apparent when it comes to illustrations of spiders, which commonly look more like caricatures than real spiders. For instance, if we look at early illustrations, the only feature that is depicted correctly is the number of legs (). What is typical for spiders, what makes them different from other arthropods, and why are they actually quite interesting? This first chapter provides a brief but concise introduction to spiders and their biology.

Spiders are distributed all over the world and have conquered all ecological environments, with perhaps the exception of the air and the open sea. Most spiders are relatively small (210 mm body length), yet some large tarantulas may reach a body length of 8090 mm. Male spiders are almost always smaller and have a shorter life span than females.

All spiders are carnivorous. Many are specialized as snare builders (web spiders), whereas others hunt their victims (ground spiders or wandering spiders). Insects constitute the major source of prey for spiders, but certain other arthropods are often consumed as well.

A spiders body consists of ). The prosomas functions are mainly for locomotion, food uptake, and nervous integration (as the site of the central nervous system). In contrast, the opisthosoma fulfills chiefly vegetative tasks: digestion, circulation, respiration, excretion, reproduction, and silk production.

Figure 1.1

(a) In medieval times spiders were depicted rather crudely and anthropomorphic. Of all the typical spider features only the number of legs is correctly shown in this wood-cut from 1491 (Hortis Sanitatis; Mainz, Germany). (b) In contrast, all main characters of a spider are correctly pictured in this copperplate engraving of a garden spider: eight legs, eight eyes, two body parts, and most important, silk producing spinnerets (Rsel von Rosenhof, ).

The prosoma is covered by a dorsal and a ventral plate, the carapace and the sternum, respectively. It serves as the place of attachment for six pairs of extremities: one pair of biting chelicerae and one pair of leglike pedipalps are situated in front of four pairs of walking legs. In mature male spiders the pedipalps are modified into copulatory organsa quite extraordinary feature, not found in any other arthropod. The opisthosoma is usually unsegmented, except in some spiders considered to have evolved from ancient species (Mesothelae). In contrast to the firm prosoma, the abdomen is rather soft and sacklike; it carries the spinnerets on its posterior end.