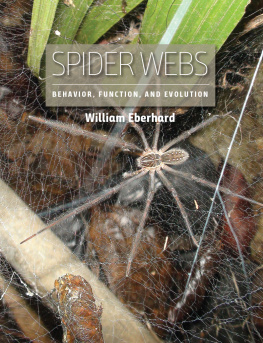

Spider Webs

Spider Webs

Behavior, Function, and Evolution

William Eberhard

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

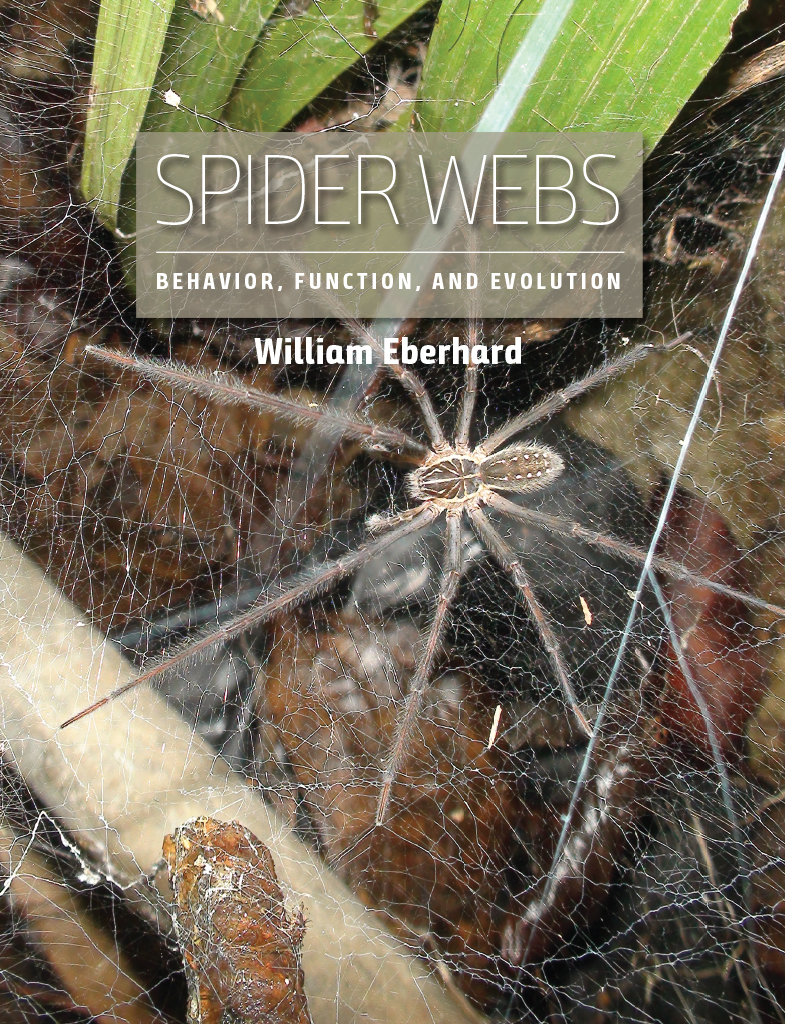

Frontispiece: The recently discovered pseudo-orb of the New Guinean psechrid Fecenia ochracea is a spectacular example of a major theme of this book, evolutionary convergence. Although the spider is not closely related to the true orb weavers (Orbiculariae) its web shares with orbs a planar, aerial array of non-sticky radial lines that converge on a hub, frame lines that support the radii, and a uniformly spaced array of more or less circular sticky lines laid on the radii. The recent nature of this discovery, and the mystery of the ribbon-like nature of the sticky lines in the inner portion of the web (such band-like cribellum lines have never been described in any other species) emphasize a second general theme: our knowledge of spider webs (especially non-orb webs) is still profoundly incomplete (from Agnarsson et al. 2012; courtesy Ingi Agnarsson)

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

Cover design and text design 2020 The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No copyright is claimed for the original text of Spider Webs: Behavior, Function, and Evolution, although some text and illustrations included in the book may be copyright protected.

For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-53460-2 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-53474-9 (e-book)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226534749.001.0001

Additional parts of this large project are archived online at press.uchicago.edu/sites/eberhard/; these portions are designated in the text with a capital O followed by the book chapter to which they refer (e.g., section O6.1; table O3.3; fig. O9.1).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Eberhard, William G., author.

Title: Spider webs : behavior, function, and evolution / William Eberhard.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019050065 | ISBN 9780226534602 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226534749 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Spider webs. | SpidersBehavior.

Classification: LCC QL 458.4 . E 24 2020 | DDC 595.4/4156dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050065

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To the memory of three great naturalists of web-building spiders:

R EV. H . C . M C C OOK, M AJ. R . W . G . H INGSTON, and E . N IELSEN

A Noiseless patient spider

A noiseless, patient spider,

I markd, where, on a little promontory, it stood, isolated;

Markd how, to explore the vacant, vast surrounding,

It lauchd forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself;

Ever unreeling themever tirelessly speeding them.

And you, O my Soul, where you stand,

Surrounded, surrounded, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing,seeking spheres, to connect them;

Till the bridge you will need, be formdtill the ductile anchor hold;

Till the gossamer thread you fling, catch somewhere, O my Soul.

Walt Whitman

Contents

Introduction

This book is about how spider webs are built, and how and why they have evolved their many different forms. It was conceived during a field trip in a spider biology course, when a student asked me why I had not written a book on spider webs. She noted that such a book would have been useful for the course but did not exist. She was right on both counts, and also that I was well-placed to produce it. I am an evolutionary biologist particularly interested in behavior. I have had the great fortune of living most of my working life in the tropics, and have spent just over 50 years watching a diverse array of spiders and thinking about their webs. Writing this book represents a chance both to contribute general summaries of data and ideas that are currently lacking, and to organize and develop new ideas that grew out of producing these summaries.

Inevitably, the books coverage is idiosyncratic. I propose more new ideas, give more new data, and discuss more extensively those topics related to behavior and evolution; some discussions in other areas, like the biochemistry and mechanics of silk, are more standard and less original. I focus on behavior and evolution partly because spider webs have the potential to make especially important contributions to resolving central questions in behavior and evolution, just as they did in the past in understanding the characteristic and limits of innate behavior (Fabre 1912, Hingston 1929). An orb web can be easily photographed with perfect precision, and it constitutes an accurate record of a series of behavioral decisions made by a free-ranging animal under natural conditions. And because a web-building spiders sensory world is so centered on silk lines, the orb is also a precise record of some of the most important stimuli that the spider used to guide those decisions; in addition, these stimuli can be experimentally altered by making simple modifications of webs. These advantages offer unusual chances to study some basic questions in animal behavior with especially fine detail and precision.

I hope that this book may help future observers to see how web-building spiders can be exploited to investigate exciting new questions in animal behavior. It is a fragment of a larger project that originally included several additional topics: the role of behavioral canalization and errors in the evolution of behavior; the importance of scaling problems in the absolute and relative brain sizes of tiny animals and the limitations in behavioral capabilities that they may impose; the organization and evolution of independent behavior units in the nervous system; the implications of chemical manipulations performed by parasitoid wasps on their spider hosts and of additional experimental manipulations of webs for how behavioral subunits are organized and controlled in the spider; and the possibility that small invertebrates understand, at least to some limited degree, the physical consequences of their actions and the role that such understanding may play in the evolution of new behavior patterns. Other fragments of this larger project are archived online at the University of Chicago Press at press.uchicago.edu/sites/eberhard/; these portions are designated in the text with a capital O followed by the book chapter to which they refer (e.g., section O6.1; table O3.3; fig. O9.1). My hope is that this book will help to project the study of spider webs back onto the forefront of studies of animal behavior.

Spiders are ecologically extremely important: for instance, a recent estimate suggests that they capture 400800 million metric tons of prey each year, or about 1% of global terrestrial net primary production (Nyffeler and Birkhofer 2017). Web spiders live in a world that is ruled by their silk lines. This world is so different from ours, with respect both to their sensory impressions and to the basic facts of what is and what is not feasible for them to do, and they have such exquisite adaptations to this world, that it is useful to briefly describe these differences here, anticipating more detailed descriptions in later chapters (references documenting these statements will be given later). My aim is to help give the reader the kinds of intuition that are needed to understand their behavior.

Next page