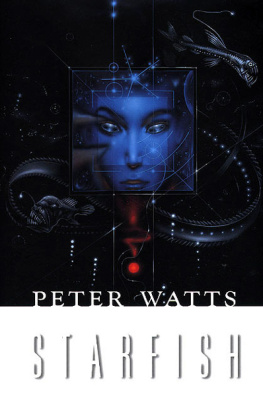

The Starfish and the Spider

The Unstoppable Power of

Leaderless Organizations

Ori Brafman and Rod A. Beckstrom

PORTFOLIO

PORTFOLIO

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2006 by Portfolio, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Decentralized Revolution, LLC, 2006

All rights reserved

Publishers Note

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. If you require legal advice or other expert assistance, you should seek the services of a competent professional.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Brafman, Ori.

The starfish and the spider: the unstoppable power of leaderless organizations / Ori Brafman and Rod A. Beckstrom.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN: 978-1-1012-1640-8

1. Decentralization in management. 2. Organizational behavior. 3. Success in business. I. Beckstrom, Rod A. II. Title.

HD50.B73 2006

302.3'5dc22 2006046262

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

To Arif, who insisted that we write,

and to our families and friends for their support

INTRODUCTION

It was like a game of Wheres Waldo. But instead of kids playing the game, the players were the worlds leading neuroscientists. And instead of Waldo, they were looking for a curly-haired, sweater-wearing grandma. Anyones grandma.

The neuroscientists were trying to answer what at first appeared to be a simple question. We all have memorieswhether of our first day at school or of our grandmother. But where, the scientists asked, do these memories reside? Little did they know that they were about to arrive at a conclusion that would have surprising implications, not only for biology but also for every industry in the world, for international terrorism, and for a host of far-flung communities.

Scientists had long assumed that our brains, like other complex machines, had a top-down structure. Surely, in order to store and manage a lifetime of memories, our brains needed a chain of command. The hippocampus is in charge, and neurons, which store specific memories, report up to it. When we recall a memory, our hippocampus, acting like a high-speed computer, retrieves it from a specific neuron. Want to access a memory of your first love? Go to neuron number 18,416. Want to access a memory of your fourth-grade teacher? Go to neuron number 46,124,394.

In order to prove this theory, the scientists needed to show that certain neurons are activated when we attempt to retrieve a particular memory. Beginning in the 1960s, scientists wired up subjects with electrodes and sensors and showed them pictures of familiar objects. The hope was that each time a subject was presented with a picture, a specific neuron would be triggered. Subjects spent hours staring at photos. The scientists watched and waited for specific neurons to fire. And they waited. And they waited.

Instead of a neat correlation between particular memories and particular neurons, they found a mess. Each time subjects were presented with a picture, many different neurons lit up. Whats more, sometimes the same group of neurons would light up in response to more than one picture.

At first, the scientists figured that it was a technological problemmaybe the sensors werent precise enough. For decades afterward, neuroscientists conducted variations on this experiment. Their equipment became more sensitive, but still they produced no meaningful results. What was going on? Surely, memories had to reside somewhere in the brain.

An MIT scientist by the name of Jerry Lettvin proposed a solution: the notion that a given memory lives within one cell was just plain wrong. As much as scientists wanted to find hierarchy in the brain, Lettvin argued, it just wasnt there. Lettvins theory was that rather than being housed in particular neurons that report to the hippocampus, memory is distributed across various parts of the brain. He coined the term grandmother cell to represent the mythical neuron that houses the memory of grandma. The picture Lettvin painted of the brain at first appears primitive and disorganized. Why would such a complex thinking machine evolve in such an odd way?