Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In memory of my mother, Betty, who had a certain flair

Objects have always been carried, sold, bartered, stolen, retrieved and lost. People have always given gifts. It is how you tell their stories that matters.

Edmund de Waal, The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Familys Century of Art and Loss

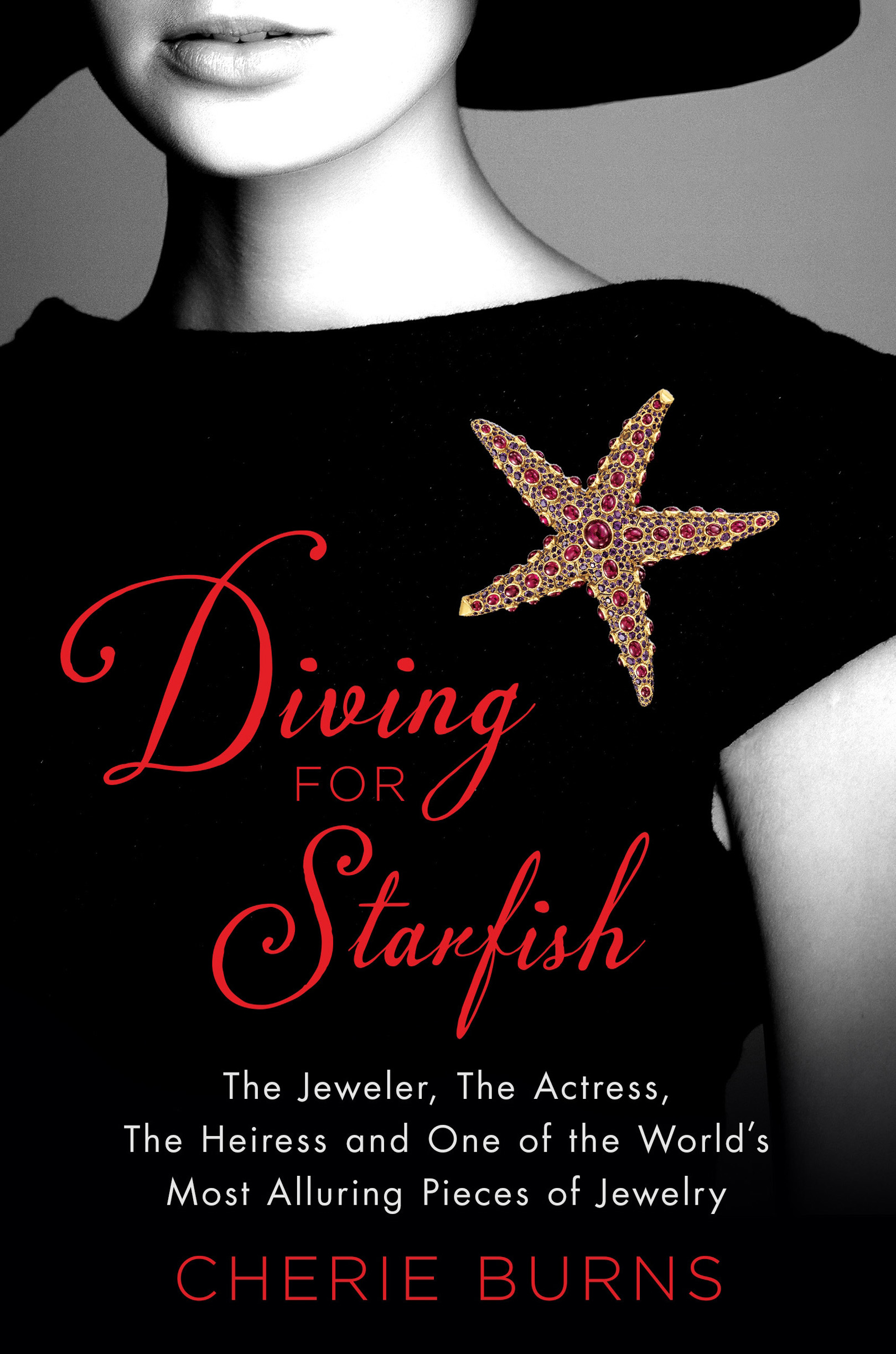

As I imagine it, a pearlescent moon rose over the mansard rooftops of Paris in the soft dusk as the streets of the First Arrondissement emptied below. Upstairs, inside a building festooned with wrought-iron balconies, sat a frail plain-faced woman sketching at her desk in a cramped atelier. Beside her sketchpad was a small collection of seashells. Some still held bits of dried seaweed and a few grains of sand in their bleached creases. Improbably (remember, I am imagining) a pungent whiff of salt spray, evoking the far-off beaches of Brittany, puffed through a window above her desk and swirled around the room. Filled with a sudden inspiration, Juliette Moutard drew a piece of jewelry in the form of a hand-sized starfish. It was a lush and throbbing likeness, rich and yet natural; an evocation of the primal sea bottom. With her paint set she colored in red rubies and purple amethysts along the ripples of its features. In my minds eye the rays undulated and the stones flung sparks into the moonlight.

* * *

Moments of real inspiration are hard to know and often more pedestrian than we imagine, but this starfish deserves a fairy-tale introduction. I cant bear thinking it had been drawn on a cocktail napkin. The unembellished fact is that in one electrifying stroke, a design that would haunt and charm jewelry aficionados for the next eighty years took shape on Moutards sketchpad. Her employer, the exacting Paris jewelry salon owner Jeanne Boivin, had urged Moutard to consider sea creatures in her designs. Europe was full of rich women, many of them Americans with newfound fortunes, flaunting their wealth and looking for innovative jewelry that would make a bold statement. Madame Boivin often brought seashells and crustaceans from the beaches of Brittany, which she knew from her childhood, and left them in the workshop of the Boivin salon.

* * *

One of the most captivating and enduring pieces of jewelry would emerge from Moutards drawing and crawl into the world of collectors and jewelers to enchant and confound them for the next eighty years. The untraditional pairing of lush purple and red stones, the miraculous articulation that mimicked life, and the legend of the Paris salon where it took form were part of its intrigue. That toile de mer, with its 71 cabochon rubies and 241 small amethysts, had five rays, two of them flipped slightly at the ends, flowing out from a center mound adorned with one large ruby. Astonishingly, its rays were articulated so they could curl and conform to the bustline or shoulders of the women who wore it. It moved. A sigh, a breath, a burst of laughter would cause small shifts of its bejeweled form.

Moutard, and Boivin, as well as the movie star and the beautiful heiress who bought the first two versions of Juliettes creation have long since vanished into eternity. But the Boivin starfish live on, casting their red and purple glow on a string of rarefied owners. The older they become, the more they are sought after. Moutard could not have known how long these brooches would continue to bewitch jewelry aficionados in Europe and America, or how many hands they would pass through from 1936 until the present. She could not have known the lives and stories they would intersect or the drama, intrigue, and deception that would sometimes surround them. All that was for me to discover.

I knew none of this, and wouldnt have cared much if I had, when I strolled down Fifth Avenue one gentle September evening eight decades later. The leaves on the trees in Central Park hadnt fallen yet and the buzz of Fashion Week, ongoing in the city, filled the streets. Fall, when the dusk drags on until the lights in the hotels and department store windows begin to glow, is always my favorite season in Manhattan. I walked slowly in high heels in the twilight, savoring the moment.

I was headed to a party for a book I had written, hosted by the exclusive jeweler Verdura. The guest list was an impressive mix of social and celebrated names. I entered the airy marble lobby of the building on Fifth Avenue off the corner of Fifty-sixth Street and walked past the black grand piano in front of the reception desk. On the eleventh floor a silver-carpeted hallway led toward Verduras door. I had been there before while reporting on my subject, the heiress Millicent Rogers. She had bought jewels from Verdura.

* * *

That night the salon was even more magical than usual. I had never been in Verdura after dark. The showrooms fill a corner looking down into Central Park. The lights of Bergdorf Goodman across the street had begun to sparkle. Large photos of Coco Chanel and the elegant Italian Count Fulco di Verdura, the salons founder and namesake, hung in their places on the espresso-brown reception room walls. Other photos, of Liz Taylor and Richard Burton, Greta Garbo, and Babe Paley, all Verdura clients, were arranged around the rooms, enveloped in a golden glow as the sun finally set.

Verdura is one of those jewelry salons too exclusive to have an entrance on the street, as Tiffany and Cartier do down below. It does not cater to passing trade. Rather, its clientele shops mostly by appointment. That night a refined calm filled the minutes before the party began. The plush off-white carpet muffled most sounds and two small but opulent front salons stood nearly empty, patrolled by two square-jawed men in tweed sports jackets. In my party mood, I spoke cheerily to them, thinking they were early guests or Verdura staff until I realized from their awkward reserve and reluctance to take their eyes off the doorway that they were security, there to protect the jewelry that was displayed in glass showcases. Diamond cluster ear clips, curb-link gold bracelets, Verduras signature Maltese crosses, hinged stone cuffs, and an array of original designs once sported by Diana Vreeland, Marlene Dietrich, and Greta Garbo, to name a fewthey all needed watching during the party.

Ward Landrigan, the owner of Verdura, greeted me. He is a well-dressed man of medium height with a shock of silver hair and an open smile. Associates who admire his sales skills say he can talk a suicide jumper off a ledge. His assured hand gestures give him an air of insouciance when he is speaking. On an earlier visit he had told me how in his salad days in the jewelry business he had been required by an insurer to keep Richard Burton, and the Krupp diamond he was delivering to him for Elizabeth Taylor, in sight until Burtons insurance coverage went into effect. For nearly a week he stayed in the Dorchester Hotel in London where Burton and Taylor slept while Burton was filming Where Eagles Dare. Hed had many tales to tell and a fine appreciation for people and jewelry. Now, he enthusiastically steered me toward the back salon, where a treat was in store.