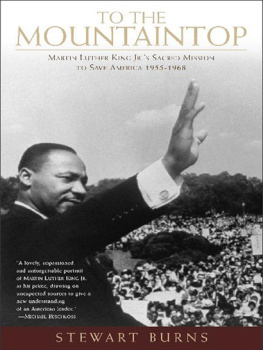

Martin Luther King Jr.s

Sacred Mission to

Save America: 19551968

To the Mountaintop

Stewart Burns

Dedicated to Rev. Dr. Robert McAfee Brown (19202001), friend, mentor, saint

Contents

(19551957)

(19631966)

(19671968)

I met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., when I was twelve and he was thirty-two, in a house of worship in my hometown. It was April 1961, a month before the freedom rides that desegregated southern bus terminals. Dr. King was spending a week in residence at Williams College in western Massachusetts. That Sunday evening he was preaching at the tall Gothic chapel up the street from my home. His sermon was called Three Dimensions of a Complete Life. As I marched down the left-hand aisle to find a seat, I found myself walking right next to the heroic preacher, awash in brightly colored robes. He looked holy. His chocolate face was glowing.

Two summers later, during the Negro Revolution of 1963, I took a month-long train trip around my country. In cosmopolitan Chicago, my first stop, a middle-aged man tripped over my feet and fell into the busy street, breaking his glasses. Despite my earnest apology, he screamed at me: Id expect that from a nigger, but not from a boy like you! Shaken, I forged on. On my return from the West Coast, I tested desegregation of Atlantas train station, quietly sitting in the colored waiting room.

In late August, I rode a chartered bus all night from New England down to the March on Washington. Standing under a shady elm tree by the reflecting pool below the Lincoln Memorial, I encountered King again, this time from a distance. His voice boomed into history on that hot afternoon.

As a civil rights historian years later, I was privileged to serve as an editor of Dr. Kings papers at Stanford University. Learning about his life and leadership has transformed my own.

...

O N THE EVE OF THAT HISTORIC March on Washington, the great African-American scholar and activist W. E. B. Du Bois died in his adopted country of Ghana. One ever feels his twoness, Du Bois wrote a hundred years ago at the height of Jim Crow repression and brutality, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.

To the Mountaintop explores how on his climb toward freedom, a divided Martin King battled for his soul, struggled to make peace between his unreconciled strivings. There was King the black man, the American, the global citizen; the fighter for black emancipation alongside the fighter for American renewal and redemption, for the redemption and salvation of humanity. There was King the lofty idealist at odds with King the rooted realist; the rock of faith beset by the sands of doubt.

Even more consequential, for his time, our time, and times to come, stood King the fiery warrior for justice and right striving to reconcile with the increasingly devout apostle of nonviolence or soul force. Like his spiritual mentor Saint Paul, he fought his way to the revelation that militant faith, however essential, would remain blind without the morning light of compassion.

Though I have the gift of prophecy, Paul confessed to the Corinthians, in words King took to heart, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing.

And now abide faith, hope, love, these three; but the greatest of these is love.

19551957

Lamb of God

Strange fruit.

Jeremiah Reeves, seventeen years old, was a popular student at Booker T. Washington High School in Montgomery, Alabama. He played drums in a rhythm-and-blues band. Like his father he drove a delivery truck. One of his stops was a house in a white neighborhood. The housewife, attracted to the handsome, dark-skinned boy, invited him in one day. They began having an affair. Neighbors took notice. Someone peeked in the window, saw them undressing, called the police. Reeves was accused of rape. He spent the rest of his short life behind bars.

Despite diligent efforts by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Reeves was convicted of sexual assault and sentenced to death. Upon turning twenty-one, he was electrocuted. Reeves was one of countless black men murdered by law or lynching for the most grievous sin against white supremacy: sex with a white woman.

During his trial a young friend of his, ninth-grader Claudette Colvin, took up collections and showed movies to raise money for his defense. His conviction made her bitter. She grieved about his wasting away on death row. I knew I had to do something, she recalled. I just didnt know where or when. She wanted to become a lawyer to help her people who were being railroaded in the racist courts.

The smart young girl lived in the rundown King Hill neighborhood surrounded by railroad yard, stockyard, and junkyards. Her mother worked as a maid. Her father mowed lawns. She had hated segregation for as long as she could remember. Her first memory of anger, when she was nine or ten, was when I wanted to go to the rodeo. Daddy bought my sister boots and bought us both cowboy hats. Thats as much of the rodeo as we got. The show was at the Coliseum, and it was only for white kids.

Her mind got pricked by a ninth-grade history teacher, Geraldine Nesbitt, who impressed on her the importance of self-worth, and to think for ourselves about what rights they had. Colvin tried to get her classmates to talk about how they could change things, but they looked at me like I was from another planet.

Nesbitt, tall and the color of dark chocolate, took pride in her blackness. Do you feel good about yourselves? she asked her students. You feel good inside? She insisted that you wont let anything stop you, regardless of your complexion.

She assigned essays about how her students felt about being black. Colvin wrote about the indignities of segregation. I felt clean, she wrote, and I didnt see why we couldnt try on clothes in the store. Furthermore, why do we have to press our hair and straighten our hair to look good?

Nesbitt read her essay to the class. Oh, Claudette! Youre crazy, her friends said. Showing the courage of her convictions, she refused to straighten her hair from that day on and wore kinky braids. Friends taunted her. Her boyfriend broke up with her. She felt it important to set an example.

Two years later, on March 2, 1955, Colvins yen for simple justice caused Montgomerys racial cauldron to overflow. As usual, the fifteen-year-old eleventh-grader rode city buses home from school. Carrying a heavy load of schoolbooks to prepare for tests, the straight-A student waited for her transfer on Dexter Avenue. Before it came she did something out of the ordinary. While her friends were shopping, she walked into Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where her teachers worshiped, and prayed.

She boarded the bus. It stopped at Court Square, where during slave auctions girls as young as she had been shown off bare breasted to rapacious buyers. Several white passengers got on, filling up the bus. The driver demanded that Colvin and her schoolmates give up their seats. They were sitting in the unreserved middle section near the back door. Her friends got up. Colvin did not move. A black girl said, She knows she has to get up. Another said, She doesnt have to. Only one thing you have to do is stay black and die.

The driver walked back to her seat. If you are not going to get up I will get a policeman. He came back with a traffic cop.

Why are you not going to get up? the cop asked her. It is against the law here. Still she did not move.

I didnt know, she replied, that it was a law that a colored person had to get up and give a white person a seat when there were not any more vacant seats and colored people were standing up. I said I was just as good as any white person and I wasnt going to get up. The cop left to get reinforcements to deal with the skinny schoolgirl weighing under a hundred pounds.

Next page