Copyright 2014 by David L. Chappell

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chappell, David L.

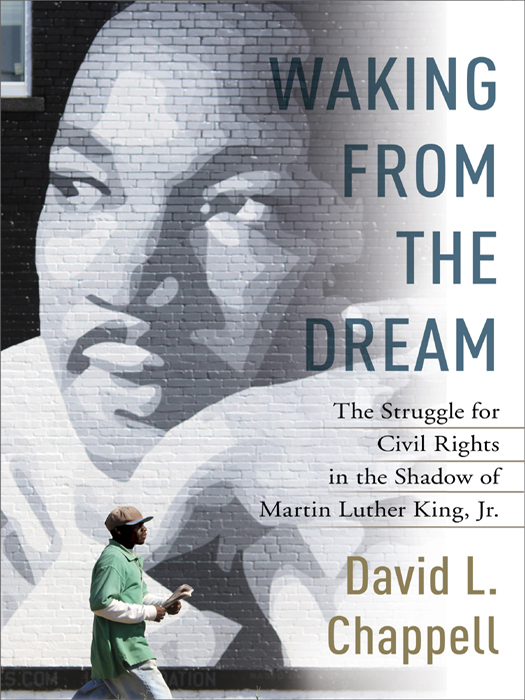

Waking from the dream : the struggle for civil rights in the shadow of Martin Luther King, Jr. / David L. Chappell.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4000-6546-2

eBook ISBN 978-0-8129-9466-7 1.

King, Martin Luther, Jr., 19291968Influence. 2. Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 3. African American political activistsBiography. 4. African American civil rights workersBiography. 5. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century. 6. United StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. I. Title.

E185.97.K5C455 2013

323.092dc23

[B]

2013009296

www.atrandom.com

Cover design: Anna Bauer

Cover photograph: AP Photo/Dan Henry, Chattanooga Times Free Press

v3.1

Introduction

Martin Luther Kings assassination marks a great turning point in American memory. In retrospect his death often appears to be the tragic, sudden end of the triumphal story of progress in civil rights, a story that Americans associate with Kings career. After the major victories of the civil rights movement in the mid-1960s, most Americans remember a dreary story from that point forward: a story of dire rhetoric over incremental bureaucratic and judicial changes in affirmative action and racial redistricting, punctuated by seemingly random flare-ups, such as the Atlanta riot of 1980, the Rodney King beating and subsequent Los Angeles riot of 1992, and the O. J. Simpson trial of 1995. There is no heroic narrative of those post-King years to match the narrative that unfolded in the King years: no tendency of the plot to run from dramatic showdown in the streets to redemptive national legislation. There is no pattern of exposing evils leading to crisis leading to remedial steps. In other words, there is no rhythm like the one that appeared to propel events from Montgomery to Selma in the 1950s and 1960s, a rhythm of long-unrequited hopes of freedom finally resolving in national recognition and substantial fulfillment. After the unraveling of the movement, the times have no trajectory, ever being corrected, toward redemption of the full promise of American lifeliberty and justice for all. The post-King years in the history of race, rights, and freedom appear rather to lurch aimlesslythe movement directionless, if not entirely stagnant.

As I attempted to take a fresh look at the post-King era, several episodes emerged as uniquely revealing, misunderstood, and undervalued in our history. These events added up to a richer, more fascinating, and more significant post-King era than has been previously recognized. The episodes in this book show that those years were full of ferment and vital experimentation in civil rights. Though some of the experiments failed, the failures proved as instructive and as important as foundations for future progress as the previous generations successes.

Many devoted and courageous Americans took up Martin Luther Kings unfinished business when he died. Over the next several years, they struggled to complete his workor the work his name symbolized to themin creative, often unexpected ways, in response to shifting circumstances. Again and again they invoked Kings name as they strove to continue and often to correct the course on which King had led a generally resistant America. Some of them succeeded in extending the principle of desegregation to the private housing market. Others attempted to consolidate and institutionalize the power of new black votes. Others attempted to remedy the economic deprivation of black neighborhoodsand to tap the creativity and energy of a long-suppressed underclasswith full-employment legislation. Others sought to make America recognize and honor Kings memory with a national holiday, a remarkable achievement that reflected a greatly weakened opposition to civil rights in an otherwise very conservative age. One of Kings most brilliant but most erratic and controversial disciples, Jesse Jackson, tried to parlay black voting power into a more active and independent voice within the Democratic Party in two quixotic presidential campaigns. Through all these episodes, Martin Luther Kings memory was put to the testand finally, when new, damaging evidence about his character was opened up for public discussion in the late 1980s and 1990s, it did not diminish his stature, or that of the cause he symbolized, in any appreciable way.

These episodes do not just lengthen the story of civil rights, but broaden and deepen it: The effort to free America from its historic legacy of slavery and institutionalized racism did not simply devolve into endless bureaucratic trench warfare over affirmative action policies, though it often looked that way, with interest groups and policy makers frozen into irreconcilable positions. Rather, it engaged the creative energies of a wide range of African-American activists, in many cases white allies, and a diverse assortment of the booming new class of black elected officials. In the years after 1968, they rediscovered some old truths and tactics. They tested the limits of equality and black power in modern America. Often, their efforts, even their successes, have been completely forgotten.

The story of the continuing struggle for rights and equality after 1968 is central to the meaning of freedom in America. The struggle of black Americans for full participation in and contribution to the full promise of American life brings to light the contradiction that haunted American history from the start: The degradation and deprivation of an entire race of people exaggerated the freedom of white Americans while exposing Americas hypocrisy to the world. Black Americans demand for their freedom raised the question whether a nation conceived in liberty, as Lincoln said at Gettysburg 150 years ago, and dedicated to human equality could endure. The story did not end with the Civil War and Emancipation or with Reconstruction and the granting of civil and political rights to the ex-slaves in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. It continued by creative, unpredictable fits and starts. It did not end again with the so-called Second Reconstruction, culminating in the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act of the mid-1960s. Nor could it be contained in the bureaucratic, partisan, and ideological channels that defined politics-as-usual after the 1960s.

Other books on the post-King years have conveyed parts of the story but, in many instances, present them in teleological and piecemeal terms. The story is, in some of these books, one of lawsuits to extend the reach of affirmative action policies, and the representation of black populations with black representatives. In other books it is a story of the undoing of school desegregation by white flight and Supreme Court retreat. What these accounts miss are the more ambitious efforts to claim large-scale public victories. They miss above all the energies expended to expand the reach of freedom and equality, rather than simply flesh out or secure rights already won, in principle and in law, in the 1950s and 1960s. The larger-scale public efforts covered in this bookeven when they failedtrace the now-flickering, now-flaring, now-fading-and-flaring-again spirit that persisted after the King years, the heyday of civil rights victories that he symbolizes in national memory.