C ONTENTS

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

I NTRODUCTION

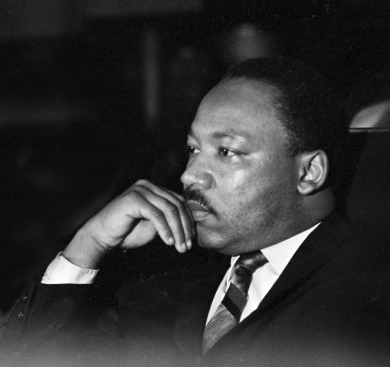

H aving shared a precious friendship with Martin King during the last ten years of his life, I was very pleased to learn that Beacon Press was returning to its important role as a publisher of his book-length works. Then, when I was asked to write the introduction for this new edition of Kings fourth book, many powerful memories flooded my being. First and most important was my recollection of how determined Martin was to be fully and creatively engaged with the living history of his time, a history he did so much to help create but also a dangerous and tumultuous history that shaped and transformed his own amazingly brief yet momentous searching life.

From this position of radical engagement it would have been relatively easy for King, if he chose, to confine his published writing to telling the powerful stories of the experiences he shared almost daily with the magnificent band of women, men, and children who worked in the black-led Southern freedom movement, recounting how they struggled to transform themselves, their communities, this nation, and our world. Instead, going beyond the stories, King insisted on constantly raising and reflecting on the basic questions he posed in the first chapter of this workWhere Are We? and in the overall title of the book itself, Where do we go from Here: Chaos or Community? (Always present, of course, were the deepest questions of all: Who are we? Who are we meant to be?)

These are the recognizable queries that mature human beings persistently pose to themselvesand to their communitiesas they explore the way toward their best possibilities. Not surprisingly, such constant probing toward self-understanding was a central element of Kings practice when he was at his best.

Indeed, it was the urgent need for such self-examination and deep reflection on the new American world that he and the freedom movement helped create that literally drove King to wrestle publicly and boldly with the profound issues of this book. Ironically, it was almost immediately after the extraordinary success of the heroic Alabama voter-registration campaignwhich led to the Selma-to-Montgomery march, and the follow-up congressional passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Actthat King realized he had to confront a very difficult set of emerging American realities that demanded his best prophetic interpretation and his most creative proposals for action.

Perhaps the most immediate and symbolic energizing event came just days after President Lyndon Johnson signed the hard-won historic Voting Rights Act, when the black community of Watts, in Los Angeles, exploded in fire, frustration, and rage. When King and several of his coworkers rushed to Watts to engage some of the young men who were most deeply involved in the uprising, they heard the youth say, We won. Looking at the still smoldering embers of the local community, the visitors asked what winning meant, and one of the young men declared, We won because we made them pay attention to us.

Building on all of the deep resources of empathy and compassion that seemed so richly and naturally a part of his life, King appeared determined not only to pay attention but to insist that his organization and his nation focus themselves and their resources on dozens of poor, exploited black communitiesand especially their desperate young men, whose broken lives were crying out for new, humane possibilities in the midst of the wealthiest nation in the world. Speaking later at a staff retreat of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, King expressed a conviction that had long been a crucial part of what he saw when he paid attention to the nations poorest people. He said, Something is wrong with the economic system of our nation. Something is wrong with capitalism. Always careful (perhaps too careful) to announce that he was not a Marxist in any sense of the word, King told the staff he believed there must be a better distribution of wealth, and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism. This seemed a natural direction for someone whose ultimate societal goal was the achievement of a nonviolent beloved community. But a major part of the white American community and its mass media seemed only able to condemn Negro violence and to justify a white backlash against the continuing attempts of the freedom movement to move northward toward a more perfect union. (King wisely indentified the fashionable backlash as a continuing expression of an antidemocratic white racism that was as old as the nation itself.)

Meanwhile, even before Watts, King and the SCLC staff had begun to explore creative ways in which they could expand their effort to develop a just and beloved national community by establishing projects in northern black urban neighborhoods. (The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, the other major Southern movement organizing force, was involved in similar Northern explorations by the mid-1960s, but both organizations were hampered by severe financial difficulties.) Partly because of some earlier contacts with Chicago-based community organizers, King and SCLC decided to focus on that deeply segregated city as the center of their expansion into the anguish of the North. By the winter of 1966, SCLC staff members had begun organizing in Chicago. At that point King decided to try to spend at least three days a week actually living in one of the citys poorest black communities, a west-side area named Lawndale. From that vantage point, working (sometimes uncomfortably) with their Chicago colleagues, King and SCLC decided to concentrate their attention on a continuing struggle against the segregated, deteriorating, and educationally dysfunctional schools; the often dilapidated housing; and the disheartening lack of job opportunities.

This book must be read in the urgent context of Kings difficult experiences in Watts and Chicago, which seemed more representative of the nations deeper racial dilemma than were the Southern battlegrounds of Selma and Montgomery. For instance, Chicago was the setting for Kings fierce reminders that the economic plight of the masses of Negroes has worsened since the beginnings of the Southern freedom movement, because slum conditions had worsened and Negroes attend more thoroughly segregated schools than in 1954.

In the face of such hard facts, King insisted on pressing two other realities into the nations conscience. One was his continuing plea for a coalition of Negroes and liberal whites that will work to make both major parties truly responsive to the needs of the poor. At the same time he insisted that we must not be oblivious to the fact that the larger economic problems confronting the Negro community will only be solved by federal programs involving billions of dollars.