Table of Contents

Guide

O ne of the small pleasures of writing this book has been talking to people all over the country about their passion. Almost everyone I spoke to caught the idea immediately; for those who didnt, all I had to do was ask, What exhibit makes people stop and say, Thats cool!? Then they got itand almost all shared my enthusiasm. So Id like to thank all those who keep Americas many wonderful small museums going and who have been so helpful to me. Ditto, of course, to the professional staffs at various halls of fame, sports organizations, and the Smithsonian.

Christopher Hunt was a helpful reader on an early version, and my brothers Cullen and Finn Murphy read the final draft. Brendan Murphy and Meg Murphy Nash read specific entries and improved them. My brother-in-law, Cary Sleeper, did brilliant photography for many items. My sister Cullene Murphy did the same with her image of Mike Eruziones stick. Another sister, Byrne Sleeper, helped keep me sane and reasonably cheerful throughout; yet another, Siobhan Grogan, helped me celebrate the end of it all with a weekend in Mexico City. My mother made a point of not asking about the book with such determination that I almost felt sorry for her, but I know she was always rooting for me, which is all that matters. And my late father, John Cullen Murphy, introduced me to the joy of sports.

My friends were wonderfully patient with how I could find a link between almost any topic of conversation and an item in the book. I consider this a neat party trick (and one, in fact, that I can keep playing). I suspect they might be less enthusiastic. Even so, their interest, even if some of it was feigned, kept me going.

For a variety of boring reasons, this book had to be written relatively quickly. I could never have finished if my colleagues at McKinsey had not supported me to a degree far above any reasonable expectation.

This is my third book. Each time, I have ventured to Thailand near the end of the ordeal for sun, sustenance, and friendship at the home of Gretchen Worth and her four-legged friends. Thanks, yet again.

Finally, thanks to my agent, Rafe Sagalyn, for selling the idea, and then for liking it, and to the staff at Perseus, who turned a jigsaw puzzle of words and pictures into a handsome book.

Also by Cait Murphy

Crazy 08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History

Scoundrels in Law: The Trials of Howe and Hummel, Lawyers to the Gangsters, Cops, Starlets, and Rakes Who Made the Gilded Age

Credit: Photo Courtesy of Dan Demetriad

Cait Murphy is an editor at McKinsey & Company, working most often on issues relating to energy and the environment. In addition, she has written freelance for publications including the Atlantic, American Heritage, Washington Post, and the Financial Times. Murphy previously worked for the Asian Wall Street Journal, the Economist, and Fortune. A lifelong sports fan and mediocre athlete, she lives in New York City.

O n a flat field that could be as short as 100 feet or as large as several hundred acres, two men start to run. Then one of them rolls The contestants maneuver their wooden spears, trying to place them through the ring. The winner is the one who comes closest.

The game was called chunkey, and it was a very big deal for hundreds of years. All the American Indians are much addicted to this game, one British observer wrote in 1775, which to us appears to be a task of stupid drudgery.

The game itself might have had a ritual purpose; some historians suggest that the rolling disc evoked the movement of the sun.

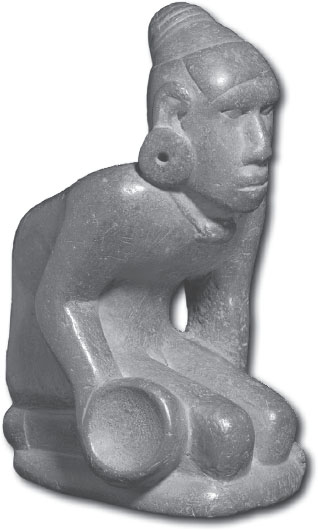

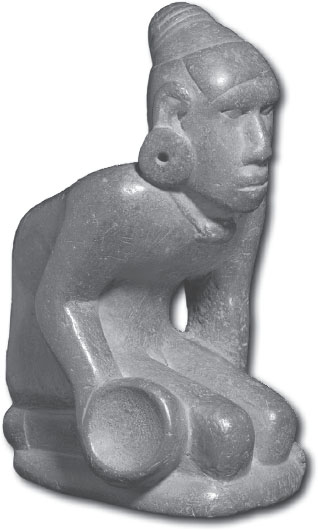

The 8.5-inch-high, red stone sculpture shown on the next page, was crafted near Cahokia, about five miles east of what is now St. Louis. Found in the early twentieth century, it shows a chunkey player with an oversized disc in his right hand; in his left he holds two somewhat undersized chunkey sticks. The figurine can also be used as a pipe.

Chunkey was played over much of the North American continent, but it was founded in Cahokia, a major urban center that used both sport and warfare to spread its culture. The largest city in North America outside Mexico, it had huge buildings, pyramids, and a grand plaza for ceremoniesand chunkey games.

So what happened to Cahokia? No one knows. One theory is that the city may have become too large to sustain itself. Another is conflict. In addition to the 120 mounds, some with entombed human remains suggestive of ritual deaths, the Cahokians also built an elaborate wall around their most important sites; this suggests fear.

Modernity played havoc with what was left. In the nineteenth century, some of the mounds were leveled to make railway beds. The biggest, known as Monks Mound, had a footprint twice the size of the Colosseum in Rome. Others were lost to farming.

The state of Illinois bought a large part of the area in the 1920s for a state park, but missed what had been the Grand Plaza (and probably the chief chunkey field); a housing development was planted there in the 1940s. In the mid-twentieth century, an interstate highway took another chunk. Since then the site has been treated better. The 2,200 acres are now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Excavations continue. Parts of about 80 mounds still exist, the most visible remnants of Americas first city.

T he Puritans have a well-earned reputation as historic killjoys. They liked rules and considered it their godly duty to keep people from the fires of hell by telling them exactly how to live. Building what Governor John Winthrop called a city upon a hill that the world would watch in awe was not a job for libertarians, and certainly not for libertines.

Naturally, then, they disdained fun and games. Except they didntat least not entirely. As early as 1622, eight years before the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, a sermon by a London-based Puritan clergyman advised that Puritans could perform their duties to God at all times, yea, even in our eating and drinking, lawful sports, and recreations. Winthrop noted that outward recreation, in the form of moderate exercise, lifted melancholy and refreshed his mind.

And that brings us to Katherine Naylors privyan outdoor toilet and rubbish pit. Naylor, a late seventeenth-century resident of Boston whose father had been banished to what became New Hampshire for nonconformity with Puritan theology, became a successful businesswoman after she divorced her abusive second husband. Naylor was also a relative by marriage of the poet Anne Hutchinson, whom the Puritans banished in 1638.

Naylor was a woman of uncommon ability and of some prosperity. That is the evidence from a 1994 excavation done in preparation for Bostons Big Dig, the mammoth infrastructure project that reconfigured the center of the city. When archaeologists uncovered Naylors centuries-old, three-seat toilet, they found a trove of artifacts, including silk, Venetian glass,

Next page