Copyright 2017 by Stephen Galloway and Orchid Hill, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Archetype, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Crown Archetype and colophon is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

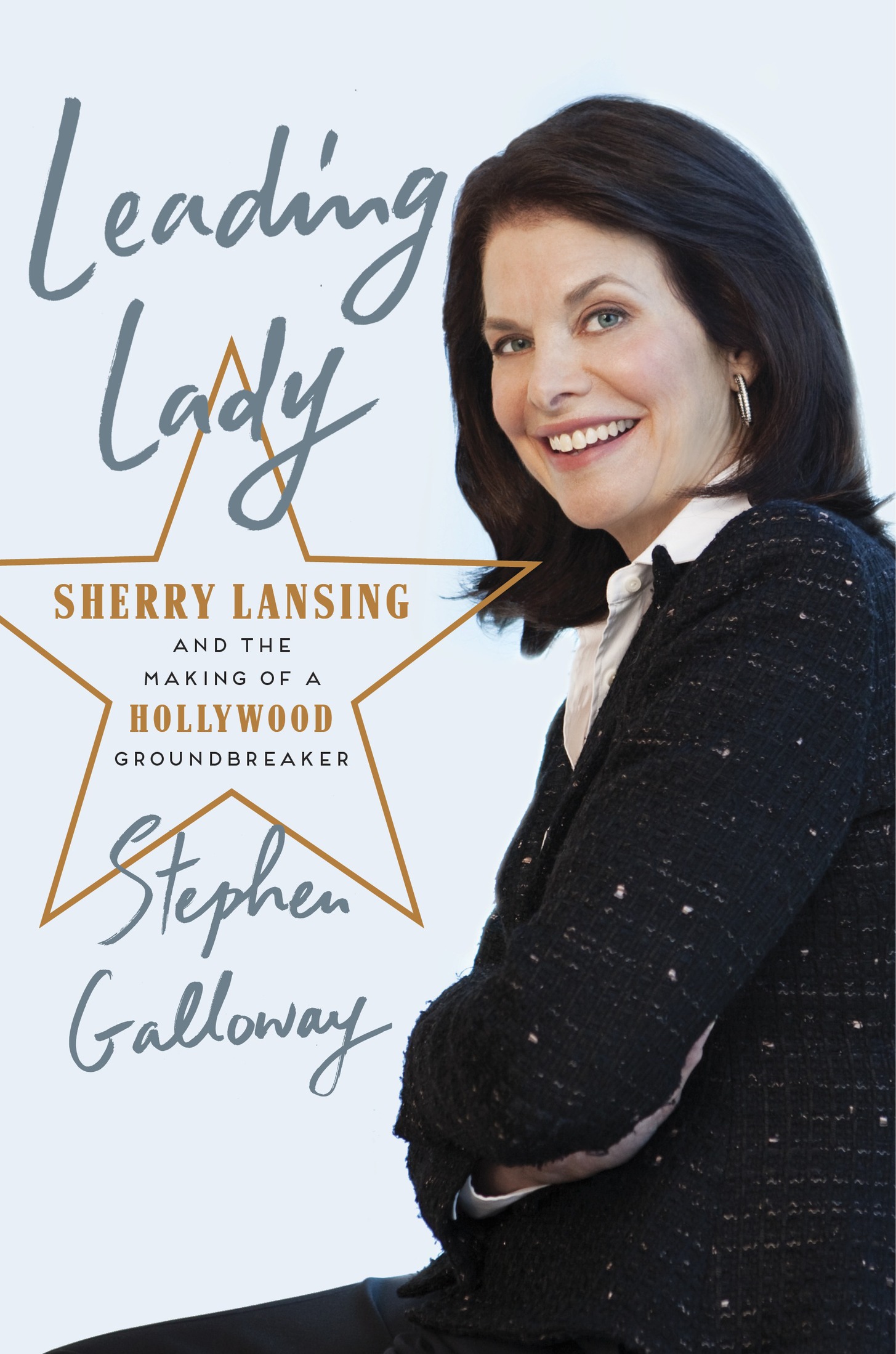

Names: Galloway, Stephen author.

Title: Leading Lady : Sherry Lansing and the Making of a Hollywood Groundbreaker / Stephen Galloway.

Description: First edition. | New York : Crown Archetype, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016035586| ISBN 9780307405937 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781101904770 (tradepaper : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Lansing, Sherry, 1944 | Women motion picture producers and directorsUnited StatesBiography. | Women executivesUnited StatesBiography. | Motion picture industryUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Motion picture industryUnited StatesHistory21st century. | Women philanthropistsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.L383 S35 2017 | DDC 791.4302/33092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016035586

O n January 23, 2003, a black sedan pulled out of Paramount Pictures historic sixty-five-acre lot at the southern edge of Hollywood and eased into the clogged traffic, heading toward Los Angeles International Airport.

For the security guards who manned the studios Melrose Avenue gate, this was nothing new: taxis and limousines went back and forth dozens of times each hour, ferrying everyone who was anyone, from Tom Cruise to Mel Gibson to Angelina Jolie. The guards knew them well, and all their follies and foibles. Some were liked, some loathed; few were as revered as the woman sitting inside the car now, her blue eyes brilliant against her raven hair.

At fifty-eight years old, Sherry Lansing was Hollywood royalty. Tall and elegant in one of her trademark Armani suits, she had been chairman of Paramounts movie division since 1992 and had ruled it with an iron fist hidden inside the most velvet of gloves. With her regal presence and commanding five-foot-ten frame, she would have intimidated the guards if not for her palpable warmth; she liked to be liked, needed it even, and unsheathed the steel within only when absolutely necessary.

For a quarter century she had reigned as the most powerful woman in film, overseeing two separate studios at different stages of her career and producing such high-profile pictures as Fatal Attraction and Indecent Proposal in between. She had weathered hits and misses, victories and defeats, enemies who masqueraded as friends, and friends who might as well have been enemies. She was as much a part of the entertainment landscape as the Hollywood sign, one of a rare breed of executives known by their first names alone. To almost everybody, she was simply Sherry.

In her present role, she oversaw a billion dollars in annual production and marketing expenses, and was responsible for green-lighting hundreds of movies, from Mission: Impossible to Saving Private Ryan to Forrest Gump. Some of these had become part of the cultural lexicon; others, less widely seen, had nonetheless filled Paramounts coffers, thanks to shrewd deals Lansing had hammered out with her business partner, Jonathan Dolgen, the blunt executive who played bad cop to her good, yin to her yang. Both were careful not to repeat the errors of the past, most famously those of 20th Century Fox, whose bloated 1963 epic Cleopatra had left the studio so broke it was forced to sell off much of its land, allowing developers to swoop in and create the labyrinthine office complex now known as Century City.

Lansings unusual ability to pick winners and avoid too many losers had given Paramount a unique stability in a town where there was next to none, where writers, directors, producers and stars lived in dread that todays success was merely a prelude to tomorrows failure. And that stability benefited not just the names that lit up the screen but also the thousands of workers, from secretaries to screenwriters, from accountants to attorneys, all linked in a golden chain leading to Lansing herself.

Because of this, she was rarely plagued by the fears that ravaged her peers, who at any moment could be toppled from their posts, losing assistants, expense accounts, fine tables at finer restaurants, trips on the corporate jet, seven-figure bonuses and above all the deference that was de rigueur in this most feudal of ecosystems, where everyone knew his place, where rich was rich and poor was poor and neer the twain did meet. Wealthy beyond her dreams thanks to a clever deal that had brought her millions of dollars when Paramount was sold to Viacom in 1994, she floated in a zone of her own, thirty thousand feet above the turbulence that buffeted almost everyone beneath her.

That, at least, was in normal circumstances. But over the past year, what had begun as a faint notion had gathered steam: that she would turn her back on Hollywood altogether.

At various moments in her long and storied career, she had contemplated weaning herself from the industry that had fed her. In her younger and less burdened days she had peeled herself free for weeks, voyaging down the Amazon, trekking across India and even living with the Maasai and Samburu tribes in rural Kenya. During those trips she had treasured life away from the rapacious rituals of Hollywood, but each time she had returned, ready to lock horns again.

Lately, however, the urge to escape had become overwhelming. Just three years earlier, she had declined to renew her contract, at a potential cost of millions in salary and bonuses, until her lawyer dissuaded her, promising there was nothing she could sign that he could not get her out of.

The past two years had been particularly taxing. Movies for which she cared passionately had stumbled at the box officeeven one of her favorites, K-19: The Widowmaker, a rare Hollywood action-adventure film directed by a woman, Kathryn Bigelow. Others had succeeded almost in spite of themselves, such as Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, the picture that made Jolie a household name, whose troubled shoot proceeded amid allegations of drug use and sexual harassment, hardly the stuff to make Lansing proud.

Nor were most star vehicles any easier. Edward Norton, whose career she had helped launch with 1996s Primal Fear, had given her endless grief, turning down roles for years even though he owed Paramount two pictures according to his original deal. When Lansing tried to book him for The Italian Job,