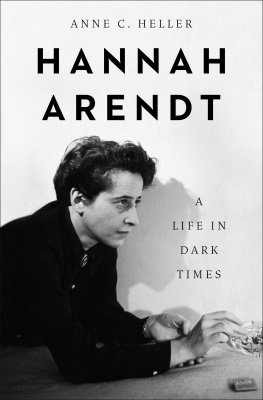

ALSO BY ANNE C. HELLER

Ayn Rand and the World She Made

Text copyright 2015 by Anne C. Heller

All rights reserved.

No part of this work may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher.

Published by Amazon Publishing, New York.

www.apub.com

Amazon, the Amazon logo and Amazon Publishing are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

eISBN: 9781477878347

Author photograph Nancy Pindrus

Cover design by Emily Weigel, Faceout Studio

Cover illustration by Antar Dayal

For David H. de Weese

Contents

Indeed I live in the dark ages!

A guileless word is an absurdity. A smooth forehead betokens

A hard heart. He who laughs

Has not yet heard

The terrible tidings.

BERTOLD BRECHT, To Posterity, cited in the introduction to Men in Dark Times by Hannah Arendt

A

Eichmann in Jerusalem

19611963

Going along with the rest and wanting to say we were quite enough to make the greatest of all crimes possible.HANNAH ARENDT, interview with Joachim Fest, 1964.

A FTERWARD, WHEN HANNAH Arendt published her book-length account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the fugitive Nazi SS officer who had helped to implement Adolf Hitlers Final Solution, the tumult the book created deeply shocked her. People are resorting to any means to destroy my reputation, she wrote to her friend Karl Jaspers soon after the book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, appeared in 1963. They have spent weeks trying to find something in my past that they can hang on me. But the trouble with her book was its theory namely, that ordinary men and women, driven not by personal hatred or by extreme ideology but merely by middle-class ambitions and an inability to empathize, voluntarily ran the machinery of the Nazi death factories, and that the victims, when pushed, would lie to themselves and comply. The book launched a pitched battle among intellectuals in the United States. It blunted Arendts reputation at its height and has cast a shadow on her legend ever since.

Hannah Arendt was seated in the press benches when the Eichmann trial opened to a tidal wave of publicity on April 11, 1961, in a makeshift courtroom in west Jerusalem. The State of Israel was only thirteen years old. and transcripts were distributed daily. Later, Arendts critics would claim that she attended too few courtroom sessions and depended too heavily on tapes and transcripts, and in fact she was on hand in Jerusalem for a total of only five or six weeks of the five-month trial. But others also came and went, while the world watched on television.

The indictment against Eichmann was read by the chief judge on the first day of the trial; it ran to fifteen counts. These enumerated crimes against the Jewish people and against humanity that had been committed or caused by Eichmann between 1938 and 1945, beginning with his alleged participation in the murderous Kristallnacht pogroms of November 1938 and encompassing the forced transportation and extermination of the majority of Jews then living in Germany, the Axis countries, and the nations occupied by the German army during the war years. The indictment listed the concentration and death camps to which Eichmann and others knowingly sent Jews for the purpose of mass murder, the approximate number of Jews sent to the camps, and the dates during which the camps operated. At the end of the reading, Eichmann, asked if he understood the indictment, spoke for the first time. Yes, certainly, he said in German. Asked how he pleaded, he answered, Not guilty in the sense of the indictment.

There were a number of reasons for the almost hysterical interest in the Eichmann trial the international equivalent of the O. J. Simpson trial in its day. At the end of World War II, hundreds of fugitive Nazi officers were rumored to be hiding and thus escaped prosecution and sentencing during the historic war crimes trials at Nuremberg in 1945 and 1946. Partly as a result, the destruction of as many as six million Jewish men, women, and children murder on a scale previously unknown in history had not been thoroughly adjudicated or even acknowledged at Nuremberg or in the successor tribunals of the late 1940s, which had focused on Germanys illegal actions against other sovereign states in Europe. With Eichmann now in the seat of judgment in Jerusalem, the full story of the Jewish Holocaust, including, for the first time, the testimony of concentration camp survivors, would finally be heard. Or so the young State of Israel expected.

Another reason was that a year earlier, in May 1960, Israeli secret service agents had extracted Eichmann from his hiding place in Argentina, sedated him, kidnapped him, and brought him to Jerusalem in a dramatic, extralegal maneuver that had been cheered, criticized, and generally debated around the world for months before the trial.

The compelling attraction for most observers and for Arendt, however, was the mysterious figure of Eichmann himself, who, for his own protection, sat sealed in a bulletproof glass cage at the foot of the judges raised platform for the duration of the trial. Slight, balding, bespectacled, with a runny nose and a compulsive twist of his thin and bitter mouth, he looked more like a ghost who has a cold on top of that, as Arendt aptly described him in a letter to Karl Jaspers, This last characterization of Eichmann turned out not to be entirely credible, as Arendt and others made clear at the time.

Everyone agreed at the outset that Eichmann was a strangely anemic-appearing exemplar of demonic evil. A high school dropout and a failed traveling vacuum-oil salesman, he was the dclass son of a solid middle-class family, Arendt recorded in Eichmann in Jerusalem, although a German historian named Bettina Stangneth has recently cast doubt on his black sheep status and painted his whole family in a darker light. He told Israeli interrogators that he had joined the Nazi Party in 1932, a year before Hitler seized power, for no particular reason except that a party official who was also a socially prominent family friend had suggested it. Soon thereafter, he was fired from his sales job, and the friend, one Ernst Kaltenbrunner, offered him a paid position in the elite SS corps of the Reich security police. By Eichmanns own account, in the following years he discovered in himself a gift for navigating large bureaucracies and orchestrating complex administrative tasks, and by the late 1930s he had caught the eye of Reinhard Heydrich and Heinrich Himmler and had been promoted from the position of a minor SS functionary to become the chief operational officer and supervisor of the transportation network that carried Jews from Germany and central Europe to concentration and extermination camps in Poland, while also establishing cooperative relations with Nazi-appointed local Jewish leadership councils and cataloging and sending to Berlin huge caches of money It was a question that Arendt was particularly well equipped to answer.

She was fifty-four years old that spring, a short, chain-smoking intellectual celebrity with an impeccable pedigree and an enormous capacity for work. Born and raised in Germany, she was the child of middle-class, assimilated German Jewish parents. She had been exquisitely well educated in German literature, classical Greek, and ancient and modern philosophy by the great thinkers of the Weimar age, including her friend Karl Jaspers and the charismatic Martin Heidegger. She had recognized and escaped the Nazi peril early, fleeing first to Paris in 1933 and later to New York City, where she lived with her husband, a German gentile called Heinrich Blcher, and spent her leisure hours joyfully cogitating with a tribe of distinguished intellectual friends that included Hans Morgenthau, Hans Jonas, Paul Tillich, Lionel and Diana Trilling, Alfred Kazin, Robert Lowell, and Mary McCarthy. She had collected prizes for her books and essays ranging from a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1952 to the prestigious Lessing Prize of the Free City of Hamburg, Germany, in 1959. But she was best known and most deeply respected for her great and difficult work of political history,

Next page