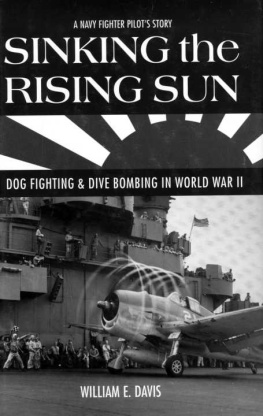

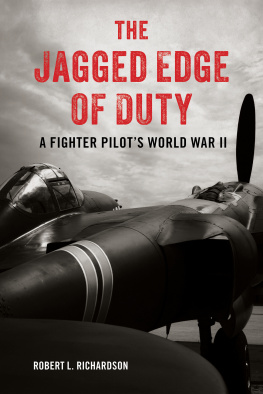

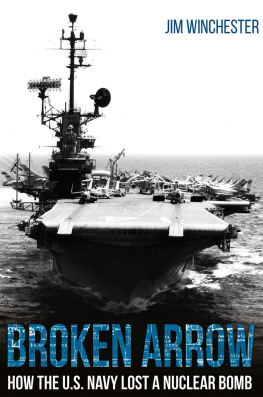

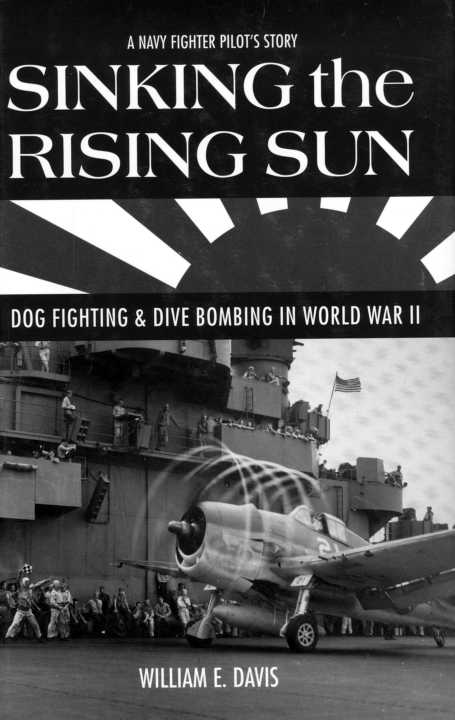

Bill Davis in an F6F on the deck of the Lexington.

.............. 8

.......... 118

.................... 134

............... 148

...................... 162

............................ 166

..... 170

...................... 176

.......................... 188

............................... 198

........................... 234

.................... 246

...... 254

....................... 266

...................... 272

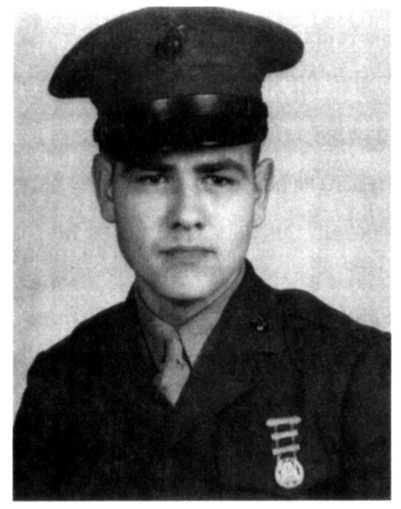

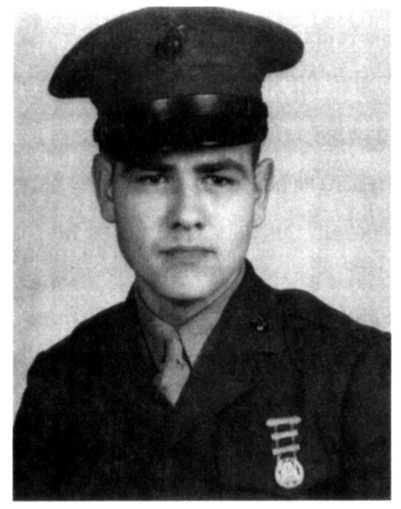

Jonathan H. Winters, III, in Marine uniform at age 18 in 1944.

efore I tell you about my friend "Bill," better known as William E. Davis, III, let me tell you briefly about my feelings about flying and wanting to be a pilot. I was born over eighty years ago in Dayton, Ohio. My grandfather, Valentine Winters, owned the Winters National Bank. He attended school with the Wright Brothers and helped finance their development of the first airplane. I was just a very young boy when my grandfather introduced me to Orville Wright. His brother Wilbur had died many years before. Along about that time I wanted to be a pilot-a fighter pilot.

efore I tell you about my friend "Bill," better known as William E. Davis, III, let me tell you briefly about my feelings about flying and wanting to be a pilot. I was born over eighty years ago in Dayton, Ohio. My grandfather, Valentine Winters, owned the Winters National Bank. He attended school with the Wright Brothers and helped finance their development of the first airplane. I was just a very young boy when my grandfather introduced me to Orville Wright. His brother Wilbur had died many years before. Along about that time I wanted to be a pilot-a fighter pilot.

But from the first grade on I struggled with math! I was tutored, failed, and finally folded completely with Plain Geometry. I knew I would never be a pilot. And so in 1943, I enlisted in the marines, and of all places to end up, I was admiral's orderly and a gunner on the USS Bon Homme Richard (CV-31). I never got to land on or take off from a carrier, but I sure saw a lot of planes.

It was when I moved to Montecito, California, that I met and worked with Bill. In my fifty years in show business, like many of us, I've met some fascinating people from all walks of life. I've met Orville Wright; Jimmy Stewart, Army Air Corps; Jimmy Doolittle, Army Air Corps; Eddie Rickenbacker, World War I ace; and Neil Armstrong. But I must stop here and mention after reading this book and knowing Bill for a number of years: if you're in need of a role model, this man ranks to me with the men I've mentioned. So put the canopy forward; you're about to take off on a wild and wonderful adventure.

-Jonathan Winters

IN 1953, JONATHAN WINTERS HEADED TO NEW YORK for the "big time" with $56.46 in his pocket. Then came The Jack Paar Show, The Steve Allen Show, and The Tonight Show, where Jonathan was able to demonstrate his comic genius. He became a top name in American comedy. Jonathan and his wife Eileen have two children and five grandchildren. They live in Santa Barbara, where Jonathan paints and writes when he is not performing.

ONE

DAY of INFAMY

ecember 5, 1941, was going to be the most important day of my life. I wanted to look good, and I wanted to be sharp. Trying to remain calm, I sat through what seemed like endless classes, nine till twelve, then ate a light lunch. I didn't want to be dull or sleepy as I had been so many afternoons as I slept through metallurgy class. The study of how to harden metals was boring, and the eutectoid diagrams involved were unfathomable.

ecember 5, 1941, was going to be the most important day of my life. I wanted to look good, and I wanted to be sharp. Trying to remain calm, I sat through what seemed like endless classes, nine till twelve, then ate a light lunch. I didn't want to be dull or sleepy as I had been so many afternoons as I slept through metallurgy class. The study of how to harden metals was boring, and the eutectoid diagrams involved were unfathomable.

This was going to be different. I brought an extra white shirt with me that morning, and went down to my locker to change for the interview. I looked at the grungy clothes in the locker that I normally changed into for foundry class, but nothing like that would suffice now. Today I had to be Mister Ivy League. I had a job interview with RCA, Radio Corporation of America, one of the largest companies in the United States. They were going to hire several engineers right out of college, and I sure as hell wanted to be one of them.

Things had changed a lot since I entered college in September of 1938. The engineering graduates the previous June were receiving few job offers, and those that were hired were getting only about ninety dollars a month. What would RCA offer, if they offered? The Depression had finally started to ease with the start of the war in Europe. In addition, the United States had started to rearm, and England would take all the armaments they could beg, borrow, or steal.

Cashing in on the good times the previous summer, I had gotten a job as a final inspector of aircraft instruments in a plant newly set up in the Philadelphia area. In the late 1920s, this plant had been the largest manufacturer of radios in the world, and Atwater Kent owned and managed it. Kent took a dim view of the candidacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 and announced to his employees that if Roosevelt won the election, he would close the plant and go out of business. The day after the election, he did exactly that, retaining only two secretaries out of thirteen thousand employees, to handle the paper work until he closed the doors permanently. The plant had remained idle until the government took it over and leased it to Eclipse Pioneer, manufacturer of aircraft instruments.

The work was tedious, but the pay was exceptional, sixty-five cents an hour. With the work days alternating from twelve to sixteen hours, I was soon at time and a half, then double time, and the last half of the week, triple time. Sunday being a day of rest, I only worked eight hours. By the end of the summer I had over one thousand dollars in the bank and the prospect of an actual job.

Climbing the steps from the locker room, I entered the marble halls of the engineering building at the University of Pennsylvania, and proceeded to the interview room. I sensed that this was a critical moment in my life. I stopped at the door and looked at my watch: one thirty exactly, engineering students are nothing if not precise. I straightened my tie one last time and knocked. A very faint voice answered, "Come in." I was on my way.

efore I tell you about my friend "Bill," better known as William E. Davis, III, let me tell you briefly about my feelings about flying and wanting to be a pilot. I was born over eighty years ago in Dayton, Ohio. My grandfather, Valentine Winters, owned the Winters National Bank. He attended school with the Wright Brothers and helped finance their development of the first airplane. I was just a very young boy when my grandfather introduced me to Orville Wright. His brother Wilbur had died many years before. Along about that time I wanted to be a pilot-a fighter pilot.

efore I tell you about my friend "Bill," better known as William E. Davis, III, let me tell you briefly about my feelings about flying and wanting to be a pilot. I was born over eighty years ago in Dayton, Ohio. My grandfather, Valentine Winters, owned the Winters National Bank. He attended school with the Wright Brothers and helped finance their development of the first airplane. I was just a very young boy when my grandfather introduced me to Orville Wright. His brother Wilbur had died many years before. Along about that time I wanted to be a pilot-a fighter pilot.

ecember 5, 1941, was going to be the most important day of my life. I wanted to look good, and I wanted to be sharp. Trying to remain calm, I sat through what seemed like endless classes, nine till twelve, then ate a light lunch. I didn't want to be dull or sleepy as I had been so many afternoons as I slept through metallurgy class. The study of how to harden metals was boring, and the eutectoid diagrams involved were unfathomable.

ecember 5, 1941, was going to be the most important day of my life. I wanted to look good, and I wanted to be sharp. Trying to remain calm, I sat through what seemed like endless classes, nine till twelve, then ate a light lunch. I didn't want to be dull or sleepy as I had been so many afternoons as I slept through metallurgy class. The study of how to harden metals was boring, and the eutectoid diagrams involved were unfathomable.