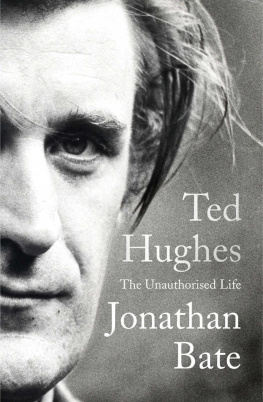

About the authors

Malcolm Knox is the cricket writer and former literary editor of The Sydney Morning Herald, and the winner of two Walkley Awards. His novels, which have been published internationally and translated into five languages, include A Private Man, winner of the Ned Kelly Award for Best First Novel; The Life; and most recently The Wonder Lover. His many non-fiction titles include The Greatest: The Players, the Moments, the Matches 19932008; The Captains: The Story Behind Australias Second Most Important Job; and Bradmans War, shortlisted in the 2013 Prime Ministers Literary Awards.

Peter Lalor is the senior cricket correspondent for The Australian and author of various books including Blood Stain, which won the Ned Kelly Award for True Crime Writing; The Bridge: The Epic Story of an Australian Icon; and Barassi: The Biography. A journalist for three decades, he has won a number of awards for his cricket writing and has worked for many publications in a wide range of roles. He covered Phillip Hughess debut Test in 2009 in South Africa and was at the SCG for his tragic last match in 2014.

Author acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their greatest appreciation to the Hughes family for their warmth, hospitality, energy, patience and kindness.

The authors would also like to thank the following, who generously gave their time to be interviewed for this book: Ashton Agar, Lloyd Andrews, George Bailey, Terry Baldwin, Sharnie Barabas, Darren Berry, Daniel Burns, Beau Casson, Steve Cazzulino, Greg Chappell, Michael Clarke, Kay Clews, Tom Cooper, Trent Copeland, David Cotton, Nathan Coulter-Nile, Ed Cowan, Jamie Cox, Brendan Cunningham, Joel Dallas, Matthew Day, Neil DCosta, Ian Dinham, Alex Doolan, Jason Ellsmore, Aaron Finch, Peter Forrest, Brett Forsyth, David Freedman, Brett Geeves, Stan Gilchrist, Darren Goodger, Mitchell Harvey, James Henderson, Michael Hill, Gregory Hughes, Helen Hughes, Ian Hughes, Jason Hughes, Megan Hughes, Virginia Hughes, David Hussey, Mike Hussey, Corey Ireland, Shariful Islam, Phil Jaques, Alan Jones, Brady Jones, Simon Katich, Simon Keen, Usman Khawaja, Virat Kohli, Justin Langer, Josh Lawrence, Warwick Lawrence, Barry Lockyer, Tim Ludeman, Mitch Lonergan, Morrie Lonergan, Nic Maddinson, Andrew Maggs, Tom Mann, Rod Marsh, Bryce McGain, Ken McNamara, Matthew Mott, Tim Nielsen, Steve OKeefe, David ONeil, Ricky Ponting, Nino Ramunno, Angela Ramunno, Steve Rhodes, Sam Robson, Ben Rohrer, Daniel Smith, Nathan Smith, Warren Smith, Ash Squire, Steve Tomlinson, Damian Toohey, Michael Townsend, Matthew Wade, David Warner, Shane Watson.

Thanks also for their assistance: Jason Bakker, Malcolm Conn, Tony Connelly, Matt Costello, Angus Fontaine, Jodie Hawkins, Phil Hillyard, Jim Kelly, Richard King, Foong Ling Kong, Jim Robson, Jonathan Rose, Danielle Walker, and especially James Henderson. Thank you to Michael Clarke for his foreword.

AFTERWORD

C RICKET GOES ON, AND it looks much as it had, but for the community that knew Phillip Hughes, it would not and could not be the same. Many tears were shed in the dozens of interviews that went into the making of this book. One cricketer confesses that he can no longer go past St Vincents Hospital. Others say the game, their lifes passion, lost its savour on the November day Phillip Hughes fell. Some would be implacably angry at Cricket Australia for cancelling only two weeks of first-class cricket in the early summer of 201415. Others accept that there was no manual to guide the handling of this situation, and that everybody managed the best they could. Some cricketers found, when they resumed, that they could not play the game the same way. All would find that they were emotionally spent by the end of the season.

From 27 November, the tributes ranged from the local to global. Paul Taylor, a 48-year-old father and former Mosman grade cricketer from Sydneys northern suburbs, put a cricket bat outside his front door at 4.08 pm that day. By the time of the funeral in Macksville on 3 December, tributes had come from around the world. Premier League football teams in England paid their respects, public figures from all walks of life recognised Phillip, and when Test cricket resumed, with New Zealand playing Pakistan in the United Arab Emirates, where Phillip had last represented his country, the sombreness of the moment drained the match of all feeling. The summers cricket in Australia, once it resumed, was played in shadow.

Virat Kohli, who had taken over the captaincy of the touring Indian team in M.S. Dhonis absence, reflects: We had to go [to his funeral] because at the end of the day we play one sport... The one thing that we have in common is the sport of cricket and that bonds us in a way; we do have rivalries and fights and arguments but the one thing that we have is cricket. We felt that we needed to be there not to show anyone that we are concerned, but because we want to be there as fellow sportsmen. It is important for the world to know that we are united as one sport.

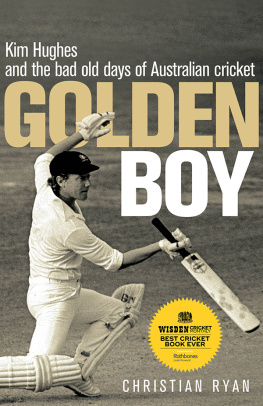

The Four O Eight farm. Away from cricket, Phillip was happiest here.

For interpretations of why Phillip Hughess death affected so many, there can be general statements about the place of sport in peoples lives and the loss of innocence to which only the hardest hearts could be immune. There was a recognition, in public grief, of the ties that bind. Hughess death was a unifying moment for cricket and for communities cross-cutting the borders of sport and nations. Life is fragile for everyone, regardless of their connection with Hughes or the sport of cricket.

But if anything has been clarified by those who have contributed to this book, it is to explain why such a reaction attended the death of this one cricketer, why so many were asking, in their grief, like Mike Hussey was, Why him?

That clarification is not in Phillip Hughess death, but in his life. The love that radiated from the sporting world in late 2014 was no fluke; it was an appreciation not only of all the general things that hold sports and peoples together, but of the unique and irreplaceable qualities of this young man. There would simply not have been the same mourning for just any cricketer. Phillip Hughes was a prodigy, a fallen idol who kept rising again, and his loss was not only of those 100 Test matches that so many believed he would play, not only a common loss of a future, but the loss of a beloved human being. For those who knew him, the loss was not having him in their lives anymore.

At the time of his passing, it seemed that millions knew Phillip Hughes. As time goes on, the circle of grief narrows back to the circle of those who really did know him. The grief remains palpable. In its presence, no words are possible. But over time, words and images and the great collection of talisman, the signed bats and shirts and the caps and the trophies, will encode memories, which are no substitute for the real thing, but will be the best we can do.

About Phillip Hughes: The Official Biography

Phillip Hughes gave his life to cricket.

And cricket gave Phillip Hughes his life.

When Hughes scored twin centuries in his second Test the youngest man in crickets 135-year history to achieve the feat the world hailed the arrival of a brilliant new star. Here was a batting prodigy from a tiny country town with a twinkle in his eye and a wizardry with the willow to fill the dreams of a generation. But those dreams were lost in November 2014 when Hughes was felled, playing the game he loved.

Told through the voices of those who knew him best,