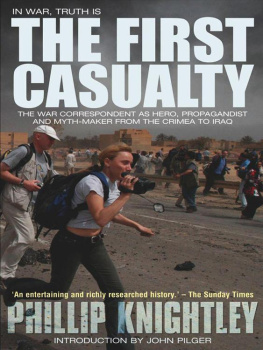

Phillip Knightley - The First Casualty

Here you can read online Phillip Knightley - The First Casualty full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2003, publisher: Gardners Books, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The First Casualty

- Author:

- Publisher:Gardners Books

- Genre:

- Year:2003

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The First Casualty: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The First Casualty" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The First Casualty — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The First Casualty" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

TO YVONNE

The first casualty when war comes, is truth.

Senator Hiram Johnson, 1917

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the following people: Caroline Gathorne Hardy, Nelson Mews, Jeremy Wilson, and Harry Roberts (in Britain); Kathlee McLaughlin, Margaret McGaughey, Susan E. Bidel, William Shawcross, and Maria Pilar Santocchia (in the United States); Julie Weston (in Canada); Antony Terry (in Germany); Desmond OGrady (in Italy); Adam Hopkins (for help on chapter 9); and James Bellini (chapter 15).

I have received valuable advice from John Swettenham, of the Canadian War Museum; Dr. G. St. J. Barclay, of the University of Queensland, Australia; Professor W. Prange, of the University of Maryland; and Dr. Peter Gifford, of Murdoch University, Australia. (My conclusions are, of course, my own.)

The late Frederick Brazier, chief librarian of the Sunday Times, and his staff gave me access to their collection of some 2 million newspaper clippings. Gordon Phillips, archivist of The Times , helped me with his historical records. The London Library provided many books that were elsewhere unobtainable.

Anne Hunt, Sue Dakin, and Lavender da Costa Fernandes typed the manuscript. Ed Barber, Sonny Mehta, and Bruce Page gave me encouragement and help. Richard Hughes steered me in rewarding directions. Hugh Atkinson set me on the road. My publishers in the United States and Britain were remarkably patient. Finally, my deepest thanks go to Ronald Whiting, for the idea, and to Tony Godwin, who took a manuscript and turned it into a book.

Introduction by JOHN PILGER

W hen I read the first edition of this remarkable book twenty-five years ago, I was struck by the following quotations. During the First World War, Prime Minister David Lloyd George told C. P Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian : If people really knew [the truth] the war would be stopped tomorrow. But of course they dont know and cant know. The truth was reported, insisted The Times correspondent, Sir Philip Gibbs, (knighted for his services), apart from the naked realism of horrors and losses, and criticism of the facts.

Robert C. Miller, a United Press correspondent covering the Korean War in 1952, was less subtle. There are certain facts and stories from Korea, he said, that editors and publishers have printed which were pure fabricationMany of us who sent the stories knew they were false, but we had to write them because they were official releases from responsible military headquarters and were released for publication even though the people responsible knew they were untrue.

Almost every word of these testimonies could apply to the wars of our time, especially the Gulf War of 1991 and the Nato bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999. Chapters covering these have been added to this new edition, making Knightleys work the most comprehensive faccuse of journalism as propaganda in the English language. It is the authors lament that, for all the dazzling advances in media technology, the media has little or no memory, as the same bogus truth is served up again and again. Reading the new material, I wondered when journalisms modern breeding grounds, the media studies courses, would begin to address the most important issue raised in this book: the virulence of an unrecognised censorship, often concealed behind false principles of objectivity, whose effect is to minimise and deny the culpability of Western power in acts of great violence and terrorism, such as the Gulf and Kosovo.

Thus The Independent could praise the miraculously few casualties in the Gulf War (meaning the few British and American casualties, most of them the result of American friendly fire), while the horror of up to a quarter of a million Iraqis slaughtered by the US-led forces was consigned to oblivion. Had this been the headline news, rather than the dubious technological triumph of the West, the public would have really known the truth, as Lloyd George said in 1917, and the pattern might not have been repeated in the Balkans. At the very least, journalists might have raised the questions that distinguish their duty to keep the record straight.

Instead, and with honourable exceptions, they were managed more efficiently than ever before. Editors were called to the Ministry of Defence and handed their guidelines. The BBC and ITV told their correspondents to fall into line. It was right, said The Economist , to suspend the normal play of democratic argument. The truth about the Gulf War must await the end of the fighting. Reporters were pressured to wear uniforms and corralled in a pool system. When the great maverick reporter, Robert Fisk, tried to slip the leash, he was told by another correspondent: Get out of here, you arsehole. Youll prevent the rest of us from working. When American bombs incinerated hundreds of women and children in a bomb shelter in a residential part of Baghdad, and several British correspondents reported that there were no strategic or military targets nearby, their patriotism was called into question and their reporting was pilloried in the tabloid press as truly disgusting and a disgrace to their country.

At the time of writing this, there is virtually no news of Kosovo, scene of Natos humanitarian war and Tony Blairs moral crusade. The expulsion and terrorising of 240,000 Serbs and Roma Gypsies from the province, now ruled by Nato, is of little interest. Who cares about Gypsies, let alone demonised Serbs? Like the Iraqis, they are the medias unpeople. The most important non-news is the unravelling of Natos justification for killing and maiming several thousand civilians, both Serbs and Kosovars, and for devastating the environment and economic life of the region. This epic destruction, according to British Defence Secretary George Robertson last March, was to stop a regime which is bent on genocide. President Clinton referred to deliberate, systematic efforts atgenocide.

The British press took its cue and the Nazis, World War Two and the holocaust were invoked. The U.S. Defence Secretary, William Cohen, said: weve now seen about 100,000 military-aged men missingThey may have been murdered. Since Nato took over Kosovo, no place on earth has been as scrutinised by forensic investigators, not to mention 2,700 media people, yet the head of the Spanish forensic team attached to the International Criminal Tribunal, Emilio Perez Pujol, has complained angrily that his colleagues have become part of a semantic pirouette by the war propaganda machines, because we did not find onenot onemass grave. Several thousand bodies have been found across the province: a gruesome toll, but a far cry from the second European holocaust. To my knowledge, the forbidden question has been asked just once. Could it turn out to be, wrote Andrew Alexander in the Daily Mail , that we killed more innocent people than the Serbs did? To that I would add: Did Natos bombs fall on innocent people partly in response to the drum beat of journalists?

One of my prized possessions is a first edition of the diaries of William Howard Russell, who was sent by The Times to cover the war in the Crimea nearly 150 years ago, a war described by Queen Victoria as popular beyond belief. In fact, as Phillip Knightley describes, it was like all wars: a catalogue of blunders, needless killing and official lies. So independent-minded was Russell that his life on the battlefield was made a misery. No satellite phone for that reporter, no e-mail, no fax. His despatches took a week to get to London by horse and steamer. Am I to tell these things? Russell wrote to his editor, or am I to hold my tongue? To which Delane replied, Continue to tell as much truth as you can. Both of them were accused of treason, until the truth of Russells courageous reporting forced the government to resign.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The First Casualty»

Look at similar books to The First Casualty. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The First Casualty and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.