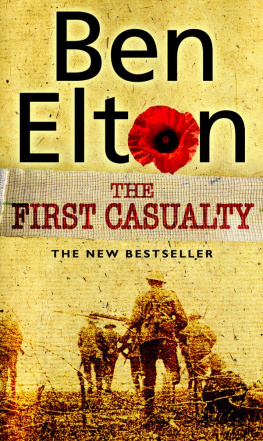

The First Casualty

by Ben Elton

(2005)

Flanders, June 1917: a British officer and celebrated poet, is shot dead, killed not by German fire, but while recuperating from shell shock well behind the lines. A young English soldier is arrested and, although he protests his innocence, charged with his murder. Douglas Kingsley is a conscientious objector, previously a detective with the London police, now imprisoned for his beliefs. He is released and sent to France in order to secure a conviction. Forced to conduct his investigations amidst the hell of The Third Battle of Ypres, Kingsley soon discovers that both the evidence and the witnesses he needs are quite literally disappearing into the mud that surrounds him. Ben Elton's tenth novel is a gut-wrenching historical drama which explores some fundamental questions. What is murder? What is justice in the face of unimaginable daily slaughter? And where is the honour in saving a man from the gallows if he is only to be returned to die in a suicidal battle? As the gap between legally-sanctioned and illegal murder becomes evermore blurred, Kingsley quickly learns that the first casualty when war comes is truth.

ONE

Ypres, Belgium, October 1917, before dawn

The soldier was laden like a pack mule.

Besides his knapsack and his water bottle, he carried on his back an iron bar around which was wound a mass of barbed wire that must have weighed a hundred pounds. Hanging from his belt and webbing were two Mills bombs, a hatchet, a bayonet, a pouch of ammunition and various entrenching tools. In his hands he carried his rifle. In addition, the man was wet through and through, every stitch of cloth and every inch of leather as sodden as if it had been deliberately immersed in water, so that it all weighed three times what a uniform, coat and boots ought to have weighed. Of course, every man in Flanders was as wet as that, but not every man carried a reel of wire on his back and so not all of them staggered as this man did or made such slow time.

You there, cried a voice, trying to make itself heard above the roar of artillery that thundered up from the guns at the rear. Military Police! Make way. I must get past. I simply must get past.

Perhaps the man heard, perhaps he didnt but if he did, he did not make way, but continued to plod steadily towards his goal. The officer could do no more than travel in his wake, cursing this ponderous beast of burden and hoping to find a point where the duckboard grew wide enough to let him pass safely. It was doubly frustrating for him to be so obstructed, for he knew enough about the nature of an attack to see that this fellow would not be advancing in the first wave. His job would be to follow on, using his wire and tools to help consolidate the gains made by the boys with the bayonets. The impatient officer did not expect any gains to be made. No gains of any significance anyway. There had not been any in the battle before this one, nor had there been in the one preceding that. Still, even gains of a few yards would need consolidation, new trenches to be dug and fresh wire laid. And so the pack mule plodded on.

Then the mule slipped. His heavily nailed boot skidded on the wet duckboard and with scarcely a cry he fell sideways into the mud and was gone, sucked instantly beneath the surface.

Man in the mud! the officer shouted, although he knew it was already too late. Bring a rope! A rope, I say, for Gods sake!

But there was no rope to hand. Even if there had been one, and time to slip it around the sinking man, it is doubtful whether four of his comrades pulling together would have had the strength to draw him forth from the swamp that sucked at him. And there was no room on the duckboard for four men to stand together, or even two, and so slippery were the wire-bound planks that any rescue attempt would have resulted in the rescuers sharing the same fate as the man they hoped to save.

And so the man drowned in mud. Dead and buried in a single moment.

TWO

Some time earlier

Douglas Kingsley was an unlikely candidate to join the ranks of conscientious objectors, in that he had killed more men than most soldiers were ever likely to do. Not directly, of course; he had not plunged in the knife or pulled the trigger but he had killed his quarry no less certainly for that. It was a point he readily conceded at his trial.

It is true that I have no small acquaintance with matters of life and death, sir, Kingsley said, addressing the judge, and have been forced to examine my conscience accordingly. I have, however, slept soundly in the knowledge that those men and the three women who were condemned to death as a result of my investigations were all heartily deserving of their fate.

It was a very public trial. Most conscientious objectors were court-martialled before military tribunals, but such was the notoriety of Kingsleys case that somehow the authorities had intrigued to bring him before a civil court. Kingsley cut an incongruous figure in the dock, not least because he was impeccably turned out in the dress uniform of an inspector of His Majestys Metropolitan Police. His buttons shone, his badges sparkled and the ribbons at his breast were an unlikely decoration for a man who stood accused of cowardice. Tall and proud, almost arrogant in his stance, Kingsley was steady and commanding in voice and manner. His tone clearly irritated the judge, who seemed to feel that some humility on his part would have been appropriate.

You think yourself a better arbiter of moral worth than His Majestys Government? he demanded.

In the circumstances under discussion, how could it possibly be otherwise?

Do not curl your lip at me, sir! the judge barked.

Kingsleys lip had indeed curled, but involuntarily. All his life those who knew and loved Douglas Kingsley had found themselves making excuses for what often seemed on first acquaintance to be an insufferably superior manner. Kingsley did not set out to patronize people but the truth was that every line on his face was wont to display evidence of his absolute conviction that he knew better than them. He was constantly surprised to discover that the fact that he usually did know better in no way mitigated peoples irritation at his all-encompassing assurance.

I will not be sneered at in my own courtroom! the judge added, raising his voice.

I do not mean to sneer, sir, and was not aware that I was doing so. I am sorry.

Explain yourself then! How is it that you imagine yourself so much more morally astute than those who govern us?

In general I would make no such claim, sir. I am merely seeking to point out that I have known every single person whom I have sent before the hanging judge and known them intimately. I have examined every available detail of their character and their actions. His Majestys Government knows none of those whom it kills, be they Germans, Turks, Austro-Hungarians or our own men.

This last comment drew cries of shame from the packed gallery of the courtroom.

Youre a traitor, Kingsley, an old man shouted, and a dirty German too!

This jibe was a reference to the fact that Kingsleys grandfather had been born in Frankfurt and his family name had been Knig.

Traitor or German, sir? Kingsley enquired. If I were German, which I am not, then I could hardly be called a traitor for refusing to fight them.

Kingsleys lip again curled, and a hail of abuse descended upon him from the gallery. Above the noise of it he could hear in his head his wifes voice scolding him for making patronizing comments. Comments she used to repeat to him angrily on their way home from dinner parties at which he had imagined himself to be the soul of reason and reserve. You think yourself so clever, she would chide, and Im sure you are, but you dont know everything and nobody likes a smart Alec.

Next page

![Le Carré - Single & single [inglés]](/uploads/posts/book/214102/thumbs/le-carr-single-single-ingl-s.jpg)