Case ():

Soldiers Tower Memorial Screen, University of Toronto

Endpaper ():

David Milne, Courcelette from the Cemetery, July, 1919.

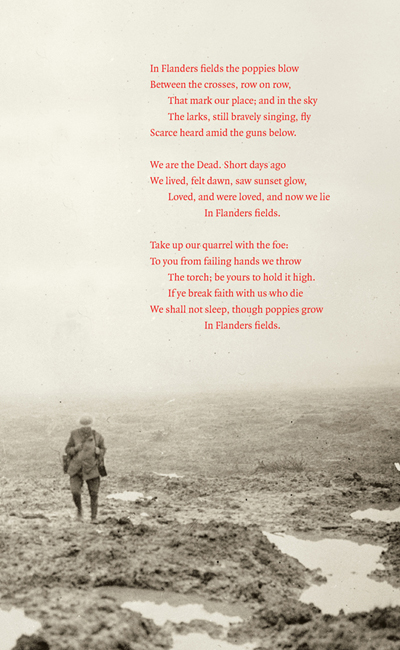

:

Passchendaele, Belgium, November 1917.

:

Valley of the Somme, France.

:

Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, Belgium, circa 1918.

:

Members of No. 1 Platoon, 3rd Divisional Cyclist Company, Canadian Army, 1915.

:

Westminster Abbey, London, 2014.

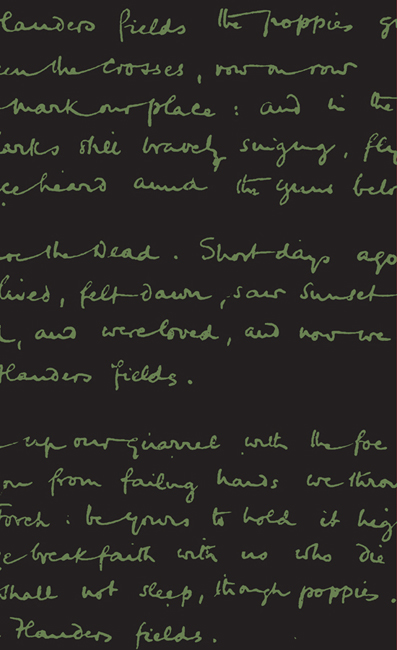

:

Detail of In Flanders Fields, in McCraes original handwriting.

:

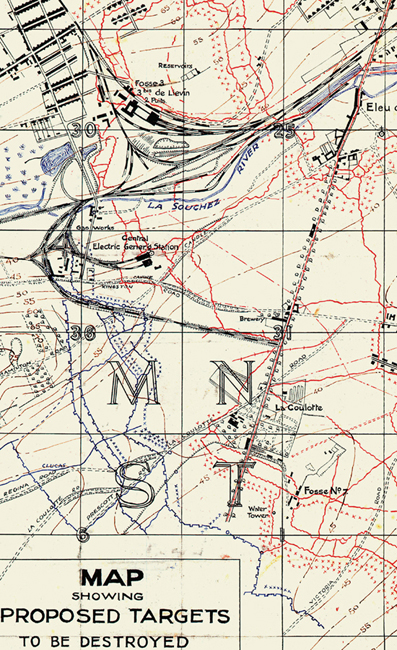

Canadian officers hand-drawn strategic map, 1917.

:

Cratered remains, Lens, France, February 1918.

:

Morning mist, Flanders, Belgium.

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

constitute a continuation of the copyright page.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2015 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Alfred A. Knopf Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

In Flanders Fields : 100 years : writing on war, loss and remembrance / Amanda Betts, editor.

Essays and poems.

ISBN 978-0-345-81025-0

eBook ISBN 978-0-345-81027-4

1. McCrae, John, 18721918. In Flanders fields. 2. World War, 19141918CanadaLiterature and the war. 3. World War, 19141918Influence. 4. Collective memoryCanada. 5. Collective memory and literatureCanada. 6. Remembrance Day (Canada). 7. World War, 19141918Canada. I. Betts, Amanda, editor

PS8525.C73Z6 2015 C811.52 C2015-902685-7

Jacket image: Nella | Shutterstock.com

v3.1

CONTENTS

Warriors Day Parade, Toronto, 1920.

Lieutenant-General (Retd)

ROMO DALLAIRE

THOSE WHO SERVE

A COPY OF IN FLANDERS FIELDS, in John McCraes own hand, hung above my desk in the Senate. When I first read it, as a boy in the 1950sdecades after it had been writtenwar had been a part of everyday life for generations. After two world wars, concepts like patriotism and unity against a common enemy felt absolute, and McCraes poem was like a torch being passed to every child, woman and man, evoking a communal understanding of the importance of sacrifice.

Today, we no longer enjoy this unity of understanding. Our country is at a restless peace, while the world is rife with conflicts that are complex, messy, unpredictable and borderless. Belligerents are playing by a new set of rules, and we still havent seen the playbook. Yet In Flanders Fields is far from being irrelevant in this new world disorder. Its timeless meaning endures, though McCraes words speak more personally now.

The power of this poem, which has survived the hundred years of war and peace since it was written, now lies in its many resonancesperhaps as many as it has readers.

WHEN MOST CANADIANS today read or hear those familiar words, on Remembrance Day perhaps, they commemorate the end of the war to end war, and the too-many wars waged since. In Flanders Fields sparks two minutes of respectful silence for the Dead, who lived, loved, and were loved. For two minutes each year, many pause to remember. Some even shed tears. But then, inevitably, many forget.

At the time the poem was published, however, Canadaand the worldwas at war. There wasnt a single person not profoundly affected and intimately involvedfrom a logger on the Queen Charlotte Islands to a suffragette in Winnipeg, from the son of an oil refiner in East Montreal to a fishermans daughter in Antigonishand especially the young men who enthusiastically joined the fight, supported by their families, their hometowns and the country as a whole.

Their patriotism was a given, and the nobility of soldiering went unquestioned. In English Canada, those few who did not support the war effort were shunned (in my home province of Quebec, things were always more complicated, though over a hundred thousand Quebecers fought in the two world wars). Men joined the fighting forces proud and eager, knowing that a bullet or a bayonet might have their name on it. That was all part of the glorious sacrifice.

But the realities of war were much bleaker. While soldiers were trained to expect death, they were not expecting chlorine gas.

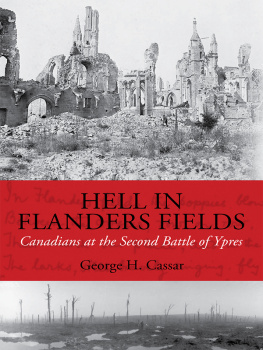

In the Second Battle of Ypres (during which In Flanders Fields is thought to have been composed), chemical attacks were used for the first time. Instead of a single shot stealing the life from his brothers, McCrae would have witnessed men dying after six to ten hours of terrible agony, turned on their sides, quite literally coughing their lungs out. The German troops who dispersed the gas were so frightened of its effects, they refused to exploit the gap in the front lines that the chemical assault created.

Most soldiers on both sides in this war were trained well enough that they could calmly weigh their own mortality under assault, except when it came to gas. A telling point: historian Jason Wilson notes that soldiers performing in the various regimental morale-boosting concert parties could tap just about any topic for their trench-side comedy routines: the futility of war, bull-headed officers, conditions on the front line, even death. Everything was fair game, with this one exception: in the minds of these soldiers, there was nothing funny about chlorine gas.