For

Maxine,

Catherine and Nicholas

Michael Jenkins has followed the professions of diplomat, investment banker and writer. As a diplomat he worked principally in European countries, and was British Ambassador to the Netherlands. When working in Moscow, he wrote his first book, Arakcheev, Grand Vizier of the Russian Empire, a biography of a minister of Alexander I. He is now Vice Chairman of the investment bank, Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein.

This book is based on a real period in my boyhood, but the telling of it owes something to my imagination and any resemblance between the characters and persons now alive is both accidental and coincidental

CONTENTS

Quelque autre te dira dune plus forte voix, Les faits de tes aeux et les vertus des rois, Je vais tentretenir de moindres aventures.

La Fontaine

I n the extreme northern part of France lies the plain of Flanders, a great fertile expanse rolling inland from the sea until it meets a chain of conical hills which, strung out like a necklace of beads, run north over the frontier to Belgium and southwards in the direction of Picardy. The plain is liberally dotted with prosperous-looking farms, whose thatched roofs and brick walls merge easily into the landscape while villages with massive church towers look down from the hills over woods and carefully husbanded fields. The magnificent skies remind you that if you are in France this is at the same time the Low Countries.

I was fourteen when I first came to the house on the edge of the plain. Some epidemic at school had, as was not unusual in those days, closed the establishment in the early summer, and my parents took the opportunity to despatch me for several months to the aunts in Flanders, mythical creatures as far as I was concerned, who had last been visited, I believe, by my father some time in the Thirties. Despite a French ancestry on my mothers side we were not related to the family and my parents had always been vague, deliberately I now think, about the origins of our connection with them.

Ever since I could remember I had been dimly aware of the existence of the aunts and their great house in France not far from the border with Belgium. My parents had stayed with the family when travelling in northern France shortly after their marriage, but my father was not a Francophile and in any case the war severed all contact during years when I might have been curious to discover more about them. If stimulated, however, he would relate lively if not always charitable stories concerning the eccentricities of les vieilles demoiselles as he liked to call them; while my mother had retained a strong impression of the beauty of the place and the kindness shown to her, a comparative stranger, on her one brief visit. It was she who on impulse decided to write to the venerated head of the family, Tante Yvonne, with the suggestion that I might spend that summer at the house, and she received almost by return a welcoming and affectionate reply, coupled with the warning that I would be unlikely to have any companions of my own age. We are all by now, I fear, rather old, but we will do our best to amuse him and I feel sure he will find plenty to do here, she wrote. In a few stately phrases she added that it would be a privilege to meet the next generation and to renew the relationship between our two families.

When the time came to leave home and make my way alone by boat and train to an unknown destination, I confess I felt distinctly queasy. But as I passed through the brick gateway perched on the front seat of an ancient black Citron beside Joseph, the gardener who doubled as chauffeur, and saw behind the trees the long faade of the house, I believe I had some premonition that a new life was about to unfold. And if after only a day the world I had left behind seemed already remote, within weeks I no longer knew which was reality, the coldness and austerity of my existence in post-war England, or the dense fabric of extended family by which I was embraced, and within whose lives I had become entwined.

As I discovered this new domain and made it my own, the long days ran into each other, forming a seamless web of time. Indeed, when I look back from this distance, it is as if everything had happened at once, a distillation of place and people never to be repeated. Only at the end did I come to understand that a world so complete and self-contained can be made to seem both an Elysium and a place of confinement; for one person a source of security and love, a shelter from outside, while for another giving rise to feelings of frustration and claustrophobia. But by then I was too involved to be dispassionate, or tolerant of any such sentiment. This was not the last occasion in my life when I would have given everything for time to stand still; and although I knew that such a state of permanence was unattainable, this realisation only led me to desire it all the more passionately.

For many years I have felt the need to write about my experiences that summer. The memory of them has lain in the recesses of my mind, slowly taking shape like a piece of coral under the sea, and occasionally brought to the surface by some chance phrase or encounter. Then a letter, recently received from one of the great-nieces of Tante Yvonne, who was seeking information about her last years, persuaded me that I should delay no longer. But as soon as I started to relive those days I realised that I had been composing this book off and on for more than half of my life, and the past and the present became one.

T he old lady is seated at one end of the long table in the dining-room absorbed in some accounts, glasses perched on her nose. With the outstretched forefinger of her left hand, circled by a large ring, she holds down the paper while with her right she is scratching some figures using an oversized pen. A large bow of lace round her neck gives a touch of style, almost of coquetry to her dress, belying her expression of intense concentration. On the wall behind her hangs a portrait of her father, a bearded patriarch, while the shadow falling across the table is unmistakably that of her sister Lise who must be reading by the windows.

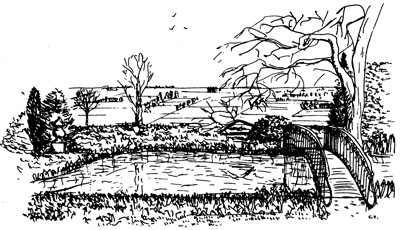

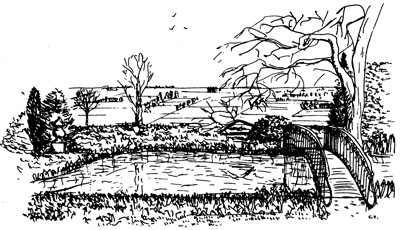

The picture was taken one summer afternoon by Tante Yvonnes nephew Bob, a keen photographer, possibly while I was sitting only a few feet away in my favourite place, the steps leading from the dining-room to the gravel terrace which ran the whole length of the houses southern side. From there you could look down over the lawn and a white bridge which crossed a small ornamental expanse of water, and beyond to a slope of fields gradually dropping into the plain. On a clear day you saw a great distance, while some trick of the light would make individual objects on the plain, such as trees or grazing animals, stand out with a startling clarity. A muddy cobbled road ran from one cluster of farms to the next, finally disappearing over the horizon in the direction of the local market town.

The prospect from the other side of the house, known as the village side, was quite different. Identical steps led from the front door, this time to a drive running into the same little road, which by now had meandered up from the plain and was passing the front of the house on its way to the village. Here the fields rose so steeply that the village walls appeared to be just above you. But if you walked up the footpath which ran from the chapel at the end of the drive and through the pasture to the village, it was ten energetic minutes before you were passing under one of the thick arches into the square, out of breath and very ready to rest for a moment on the stone bench set into the wall of the church.

Next page