Published by Zebra Press

an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd

Reg. No. 1966/003153/07

Wembley Square, First Floor, Solan Road, Gardens, Cape Town, 8001

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

www.zebrapress.co.za

First published 2013

Publication Zebra Press 2013

Text Chris Schoeman 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

PUBLISHER: Marlene Fryer

MANAGING EDITOR: Robert Plummer

EDITOR: Lynda Gilfillan

PROOFREADER: Bronwen Leak

TEXT DESIGNER: Jacques Kaiser

TYPESETTER: Monique van den Berg

INDEXER: Sanet le Roux

ISBN 978 1 77022 499 5 (print)

ISBN 978 1 77022 500 8 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 77022 501 5 (PDF)

Contents

Authors note

A SPECIAL WORD OF thanks to Mr Jonathan Evans, Trust Archivist at Barts Health NHS Trust, London, for information on Clara Evans; Ms Ruth Fitzmaurice of Cape Town, for the use of the original letters of her grandmother, Margaret McInnes; Mr Mark Wilkie of Douliou, Taiwan, for information and photographs of his great-grandmother, Margaret McInnes; Mr Robert Millar of Ontario, Canada, for information on his grandmother, Maud Graham; Prof. Kay de Villiers of Cape Town, for helpful information on nursing during the Anglo-Boer War; Mss Mimi Seyffert and Melani Ismail of Special Collections, Stellenbosch University Library; Ms Etna Labuschagne of the Anglo-Boer War Museum, Bloemfontein; and the staff of the Simons Town Museum.

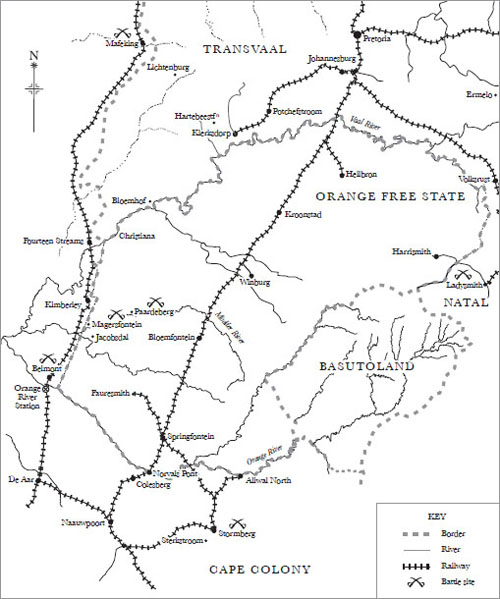

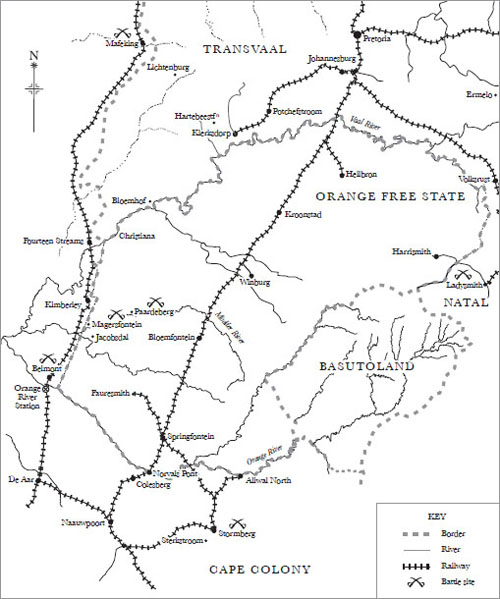

Orange Free State and Southern Transvaal, c. 1900

Introduction

I N THE LATE nineteenth century, many women began to realise that the world was opening up to them. They became aware of the exploits of women travellers, explorers and missionaries, such as Mary Kingsley, Isabelle Eberhardt and others. By then, with the rise of the suffrage movement, the stage of war was no longer the exclusive domain of men, and women were increasingly claiming their share in upholding the honour of their country.

After the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Boer War in October 1899, hundreds of women left for South Africa to assist in the war effort. Their reasons were varied: some had philanthropic motives though with no real intention of roughing it in the bush or on the open veld while others went for the sheer excitement, or, perhaps more dubiously, in the pursuit of pleasure. But there were also those who had a genuine desire to do good and to help the victims of war. The women came to Africa from all over the world from British colonies such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and from pro-Boer countries such as Holland, Belgium and Germany but whatever their origins, they all came to live and work under harsh conditions that were quite foreign to them.

This book tells the story of those altruistic women two of whom died during their ministrations and while the backdrop is the brutalities of war, this is also a story of the lighter side of life in South Africa at the time. Based on the womens diaries and letters, as well as other wartime sources, this is a tale of endurance; of dealing with scorching heat, freezing cold and suffocating dust, the threat of snakes, scorpions and soldiers; and, probably worst of all, of dealing with the sad eyes of the dying men under their care, as they ached for mothers, wives and sweethearts far away.

Anglo-Boer War literature has, somewhat inevitably, focused largely on the men who fought on either side: Boer generals Christiaan de Wet, Koos de la Rey, Louis Botha and Captain Danie Theron, and British military officers Sir Redvers Buller, Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener. While the lives of prominent women such as Emily Hobhouse, Johanna Brandt, Sarah Raal and Tibbie Steyn have been well documented, many others have been sadly neglected. Apart from Mary Kingsley, the angels of mercy featured in this book were not prominent figures, but they were nonetheless important and influential in their own way. While these were ordinary women with whom we can easily relate, their achievements were extraordinary; and though their experiences and contributions varied, each one of them was compelled by the desire to do something meaningful for her fellow man.

It was especially in the spheres of nursing and teaching that foreign women made a significant contribution during the Anglo-Boer War. Yet even prior to that, in the colonial context, there had been a relationship between the drive for female suffrage and the emergent profession of the female nurse; both involved women who were striving for recognition, and who were genuinely concerned with social justice. The war offered women in the colonies an opportunity to contribute both to the national and the imperial cause. The idea of women operating outside of the domestic sphere was, however, still viewed with suspicion, and the matter created much debate throughout the colonies. Nevertheless, the work of the nurses in South Africa demonstrated that not only were women able to operate successfully in the public sphere, but they could do so without losing their femininity as prescribed by society. At the time, there were preconceived notions regarding women, who were expected to be attractive not only in appearance, but also in their manners and speech, and to be mindful at all times of their social position. In spite of the difficult conditions in which women worked during the war, they were expected to continue to fulfil these requirements.

At the height of the war, about 300 women teachers from Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand were recruited to work in the concentration camps that the British had set up for Boer women and children. Thousands of predominantly lower-middle-class women applied for these teaching posts, and while some were motivated by patriotism, many desired adventure and a better life. The success of the schools they came to teach in raised imperial hopes somewhat naively, as it turned out that education could transform the former Boer republics into British territories within one generation.

The women featured in Angels of Mercy came from a variety of backgrounds and occupations. Some were authors and adventurers, such as the Belgian socialist Alice Bron, and Mary Kingsley, one of two Englishwomen who died while caring for Boer patients. Others were nursing sisters, such as the Australian Nellie Gould, one of that countrys first Boer War nurses, Georgina Pope from Canada, Lisette Hellemans from the Netherlands and Elin Lindblom, a Swede who served with the Scandinavian Ambulance. Some were teachers: Maud Graham from Canada, Margaret McInnes from Australia, Hilda Ladley from New Zealand and Wijtske Sijbrandi, who had come from the Netherlands and eventually ended up nursing as well. At times during the war their paths crossed Wijtske Sijbrandi, Lisette Hellemans, Elin Lindblom and Alice Bron encountered one another in strange circumstances at one point.

Some of the stories in this book have previously been published; among them are the wartime experiences of Lisette Hellemans (Met het Roode Kruis mee in den Boerenvrijheidsoorlog), Alice Bron (Diary of a Nurse in South Africa) and Maud Graham (

Next page