This book is dedicated to the

memory of my father,

Leslie George Semple,

whose diary, scrapbook and

photograph albums were the

starting point for my research.

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Pen & Sword Aviation

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Clive Semple 2012

9781783031900

The right of Clive Semple to be identified as Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13pt Palatino by

Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen &

Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History,

Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

My thanks are mostly due to the successive governments who have maintained the National Archive at Kew at taxpayers expense. Tucked away in cardboard boxes are the minutes and correspondence of all the ministries for whom records survive. They sometimes reveal well-documented history that conflicts with the traditional version of events that senior politicians and, in this case senior RAF officers, have chosen to present in their semiofficial history books. It was the conflict between the truth and these history books that led me to write this account of No. 1 Aerial Route RAF. The first flight to Australia is an integral part of this project so this has also been included in the story.

The Imperial War Museum, The National Archive, the Australian War Memorial and an archive of contemporary photographs from David Hales of a South Australian agency called Optical Design are all to be thanked for supplying most of the pictures. A few were supplied by Chaz Bowyer before he died. The remainder come from my fathers photograph albums, were taken by me or are out of copyright.

CHAPTER 1

Bad Landing at Centocelle

It was May 1919. The big Handley Page bomber left Pisa at 5.30 p.m. on the 17th and did not arrive over Centocelle until the light was failing. From the air it is difficult to detect slopes until one is close to them and the pilot, Frederick Prince, misunderstood the landing T and approached downhill. There was no wind and the plane landed too fast. There were no brakes on a Handley Page so it was in danger of overrunning the landing field. Prince switched on his engines again, opened the throttles and tried to go round for a second attempt. As the plane struggled to rise one wing hit a tree and the machine smashed into a road at the edge of the field. Prince was killed outright and Sidney Spratt, his observer and reserve pilot, who was sitting beside him in the nose of the machine, died hours later in hospital.

There was another man sitting in the rear gunners cockpit and thus protected from the full force of the impact. He was trapped in the wreckage for a time until rescued by the mechanic, Frederick Daw, who had been thrown clear. The other man was T.E. Lawrence, well known and trusted by the Arabs and famous in England as Lawrence of Arabia. Lawrence suffered concussion, a broken collar bone and badly bruised ribs and he was taken to hospital where he remained until the end of May.

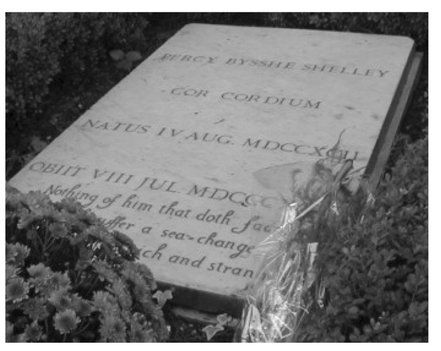

While Lawrence was slowly recovering in hospital, Prince and Spratt were buried with full military honours in the St Paolo cemetery for non-Catholics, symbolically located just outside the city walls of Rome. The British Ambassador and the head of the Italian Air Force attended and a firing party from the Italian Flying Corps fired a volley over the graves. Only a stones throw from their graves is the tombstone that marks the spot where the ashes of Percy Bysshe Shelley are interred. Shelley had visited the cemetery not long before he was drowned in 1822 and had written of it:

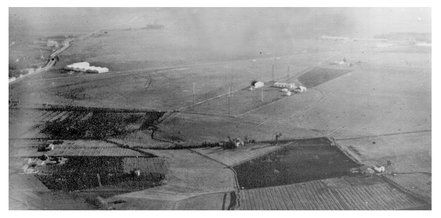

Centocelle airfield in 1919. Looking down from the air it is not easy to detect the slope of the landing ground. The airfield is now a heavily built-up suburb of Rome inside the ring road. (Air1/2689/15/312/126)

The English burying place is a green slope near the walls and is, I think, the most beautiful and solemn cemetery I ever beheld. To see the sun shining on its bright grass, fresh when we first visited it, with the autumn dews, and hear the whispering of the wind among the leaves of the trees, is to mark the tombs of the mostly young people who are buried there. One might, if one were to die, desire the sleep which they seem to sleep.

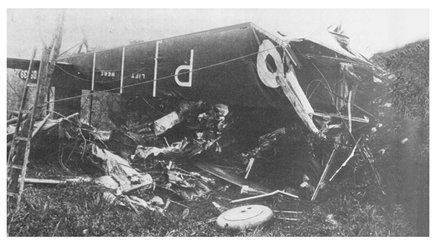

The remains of the Handley Page D5439 that crashed at Centocelle. It is upside down and only the rear of the fuselage and the tail survived intact. (Chaz Bowyer)

See photograph in the colour section.

The two new graves matched Shelleys comment about mostly young people. Frederick Prince was twenty-seven and Sydney Spratt was just nineteen. Ninety years later the crash was remembered by a commemorative service on 19 May 2009 conducted by the Canon of St Marys Anglican Church in Rome. A handful of Britons attended that service but the rest of Britain knew nothing about it or the reason for the Handley Page being at Rome all those years ago.

Shelleys tombstone. Only his ashes are buried here because his body was burned by Lord Byron and Leigh Hunt on the beach where he drowned in the Gulf of Spezia in 1822. Shelley was returning from a visit to them when his boat was caught in a storm. (CS)

In 1919 few other aeroplanes anywhere in the world had flown as far as this. Those that had were all Handley Pages. Why was a boy of nineteen making a pioneering flight and why was Lawrence there? The answers illuminate a fragment of history that has been concealed for the last ninety years.

Lawrence was on board because he had thumbed a lift to Cairo. He had been attending the Paris Peace Conference as advisor to Prince Feisal, son of the King of the Hejaz, and he was disillusioned by the Machiavellian manoeuvres of the British and French Governments as they tried to take control of the Middle East to fulfil their own post-war strategies.