Boy with a White Flag

MEMOIR OF WORLD WAR II GERMANY AND

THE POST-WAR YEARS

Karl Heinz Strick

with

Frances L. Strick

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.Copyright 2011 by Karl H. Strick

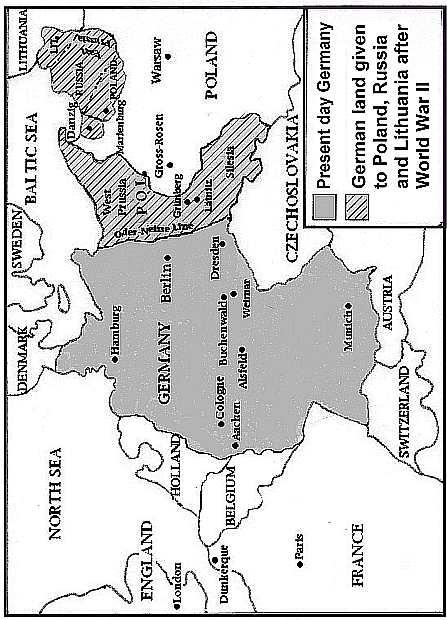

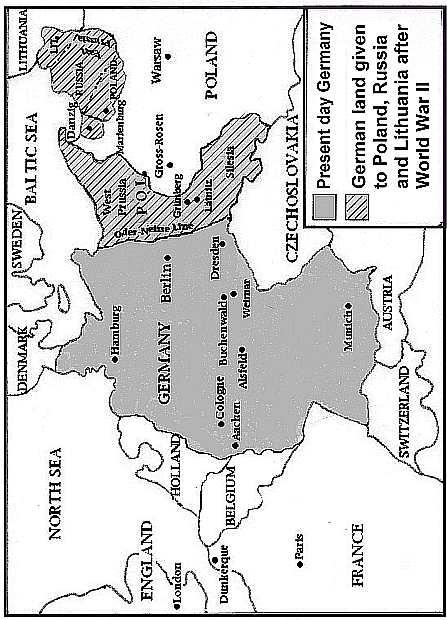

Map of Germany Before and After World War II

Contents

PREFACE

FALL 1991

In 1991, I traveled from Birmingham, Alabama to Europe, found the Polish hamlet of Ltnitz, and retraced the roads I had first walked as a seven-year-old, 49 years earlier. The stationmaster's house where Mutter and I had spent two years, starting in 1942, away from the bombing raids of Cologne, was easy to find. The sign on the tiny train station now read Letnica, the Polish equivalent for the German Ltnitz . The nearby dairy was defunct.

I knew the Polish border had shifted westward to the Oder-Neisse Line at the end of World War II, thus giving a large part of German territory back to Poland. This had forcibly displaced millions of Germans. Still, the completeness of the ethnic transformation surprised me.

Everybody I initially encountered spoke only Polish or was too hostile to speak to a stranger driving an Audi with German license plates. For my mission to succeed, I needed to find someone willing to speak to me in German, English, or French. A group of young men loitering in front of a rundown apartment building appeared friendly from a distance; however, as I slowly drove toward them I noticed their vodka bottles. Their anger became palpable when they recognized my car.

I recalled the warning of the hotel manager in Zielona Gora the night before. "The Audi is a frequent target of thieves. You'd better keep your car in a locked garage during the night and avoid driving it in secluded places. Not all my compatriots feel friendly toward strangers." I waved at the drunks and stepped on the gas, making the Audi do a little dance on the rain-slicked road as it accelerated out of harm's way. An empty vodka bottle shattered harmlessly as it hit the road behind me.

The cemetery was on the mile-long stretch of deserted road connecting the train station to the actual hamlet of Ltnitz. As a child, I had passed the cemetery on my way to school and sometimes stopped near a new grave to admire flowers piled on a fresh mound of earth. The gaudy fence made from scrap metal stampings was new to me. Never losing sight of my car, I entered the cemetery, systematically crisscrossing the overgrown pathways. Among mostly wooden crosses with barely legible markings were a few headstones, all bearing unfamiliar Polish names. The oldest readable markers dated back to 1946. Perplexed, I asked myself where all the graves were of people who were buried before 1946.

Studying tombstones in search of familiar names was the foundation of my ill-prepared, fact-finding mission. I wanted to determine if there were graves marked with the names Ulrich, Schiele, and Schmalfeld, all dated in the fall of 1944. The existence of such graves would indicate that near the end of World War II, when control of this region changed violently from German to Russian hands, the slave laborers from the dairy had indeed carried out their threatened revenge killings. It would also lend credence to the existence of a "hit list" which, according to my friend Maria, had contained my mother's and my names.

Back at the car, I was taking a final picture when I noticed a cyclist laboring up the gentle slope. Dressed in comfortable green clothes meant for hunting, he looked old and harmless, and I decided to wait for him. He dismounted near the top of the incline, slowly pushing his bike up the remaining grade. He grinned when he finally reached me and said something in Polish.

Shrugging my shoulders, I asked, " Sprechen Sie deutsch ?"

He pondered his response and then answered in German, "My wife is German, but we don't speak her language too often."

Delighted, I shook his ice-cold hand and blurted, "What happened here at the end of World War II? Were there any revenge killings by the slave laborers?"

His smile disappeared, and after a long pause he said, "I'll be 75 years old in a few months, and each month this darn hill gets steeper. I'm getting too coldI must hurry home before it rains again."

As he rode away, I pleaded, "Did you understand my question?"

He simply said, "You are looking at the wrong cemetery; this is the Polish cemeteryall the Germans are buried over there." He pointed at an area adjacent to the scrap metal fence. All I could see was a stand of mature trees towering over impenetrable underbrush.

With renewed hope, I reentered the Polish cemetery and walked along the fence, trying to spot German gravesites on the other side. No luck. It would take sturdy boots, suitable clothing, and a machete to clear away the brush. I had neither the equipment nor the time to do this. Disappointed and tired, I leaned against the fence and shut my eyes for a moment as my mind painted a picture of little Adolf Schmalfeld and his parents lying in their graves nearby. I felt grateful to be alive.

A sudden burst of rain splashed me back to the reality of an impending border crossing followed by a long drive. Traversing Ltnitz, I stopped briefly at the inactive blacksmith shop next to the Catholic church, took another picture, and then focused on the long road back to Frankfurt.

Trying to kill a few hours in the Frankfurt airport the next morning, I started to write another article for The Spokesman of the Birmingham Bicycle Club. The old Polish cyclist with his antiquated equipment and quaint clothing seemed to make a good subject; however, after only a few paragraphs, strangely and inexplicably, I began to cry. Embarrassed, I moved to a different part of the lounge only to continue to produce more tears than sentences.

The boredom of the nine-hour flight motivated me to start writing again, butstill more tears. It now became clear that I had started more than a short story about cycling. Disregarding the curious glances from fellow passengers, I focused on writing the first draft of part of this book. The draft marinated at home for a few months until the Christmas holidays. After a review of my notes and a few laborious starts and stops, the dam finally broke and my mind bridged the gap of 47 years. I spent the next several days writing longhand and nonstop about long-suppressed memories.

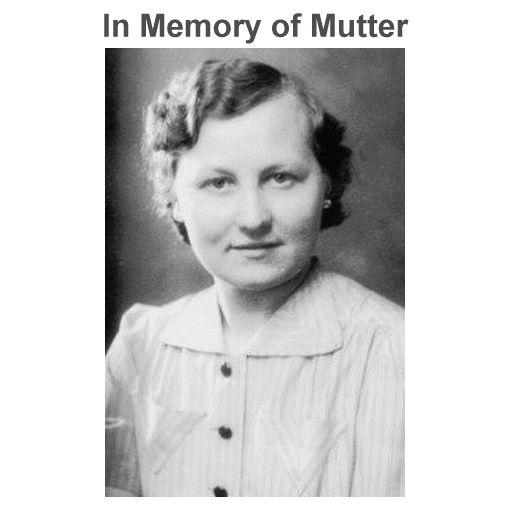

I was five years old when my father went to war, and Mutter took complete charge of my well-being. She worked hard to protect me and put food in our mouths. When all else failed we survived by begging, bartering, and sometimes even filching. Mutter maintained her uncanny storytelling ability almost to the end of her 92 years. She told and re-told stories of humorous and tragic events, enhancing my memories of them far beyond what I would have retained without her tales.

This is an account of a boy and his remarkable mother. The story unfolds during World War II when civilians were fleeing from cities to escape the bombings, Jewish people were being persecuted, and people with severe mental and physical disabilities were being euthanized.

My relatives included Onkel Karl Heinrich and Onkel Fritz, the first an SS trooper and the second a Jewish lawyer, obstreperous Polish Opa Stroinski, a hard-working foundry worker during the week and a poacher on weekends, and my Onkel Andreas who hid his hatred of Hitler barely enough to stay out of jail. The story chronicles the harrowing path of a boy who connives and steals to stave off hunger. He experiences the unexplained disappearance of a disabled friend and comes within smelling distance of the Buchenwald concentration camp.