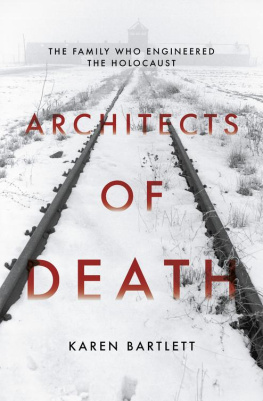

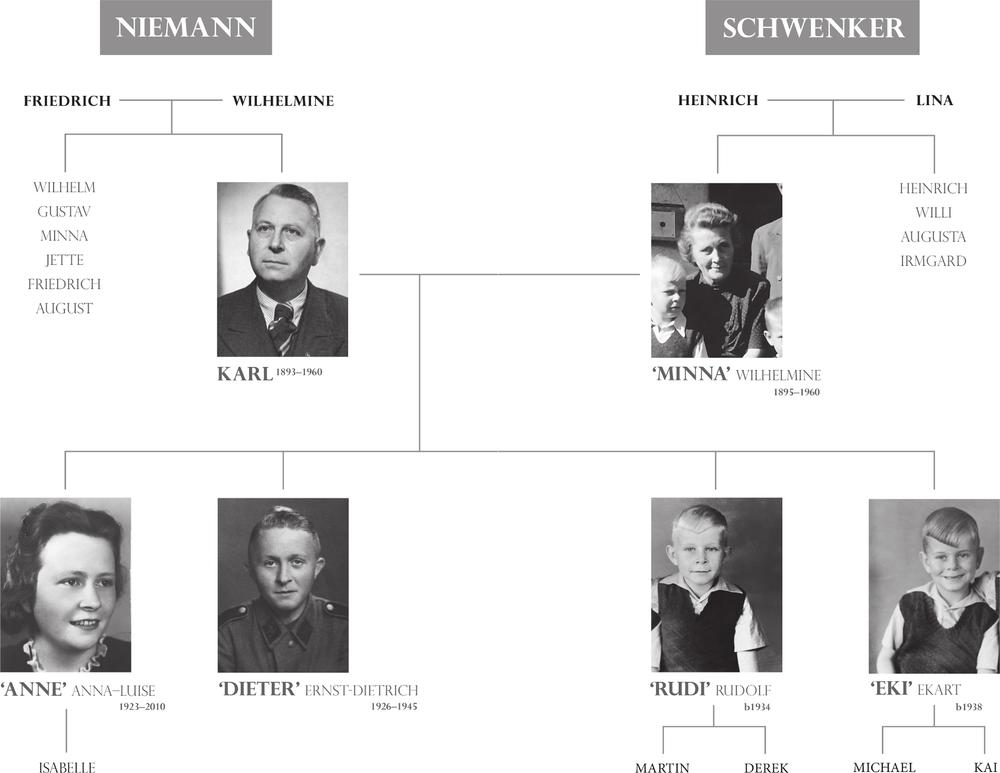

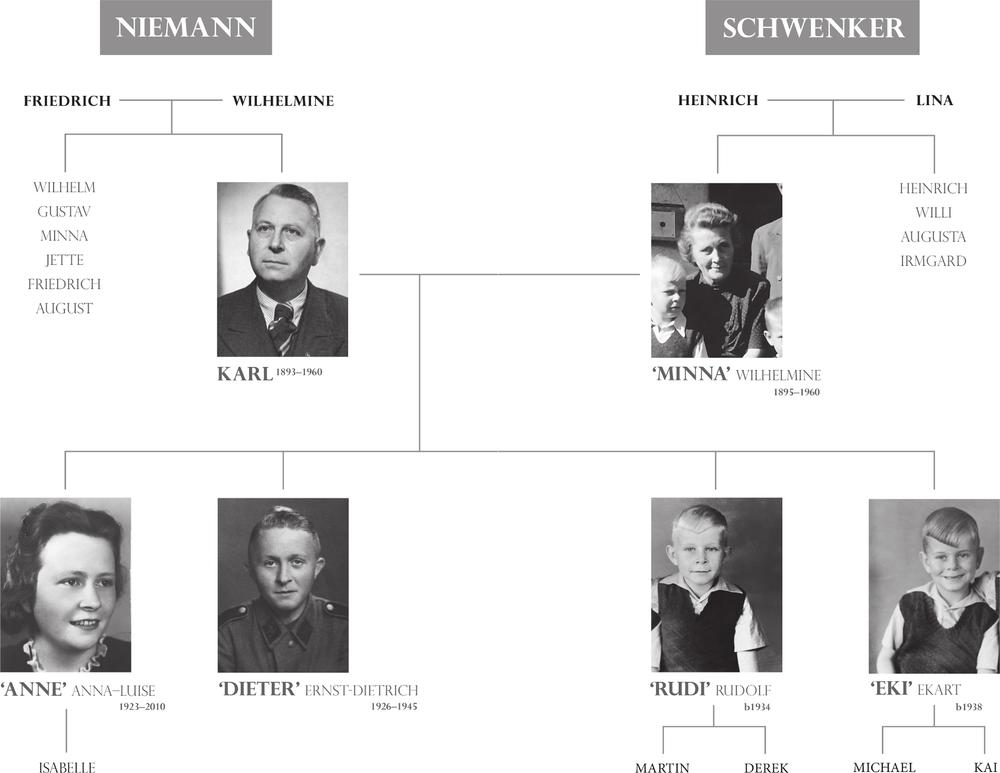

I was at Dachau. No, not as an inmate I was one of the bad Germans. I used to tell people I was in Munich, but no, I was at Dachau. Rudolf Adolf August Martin Wilhelm Niemann(my dad)

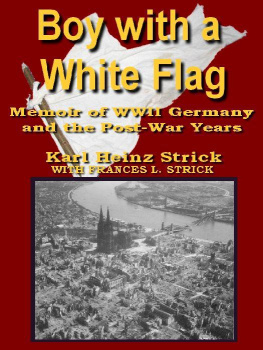

F or most of his life, my father kept the story of his early childhood hidden away from the world, his children, even perhaps, from himself. Both he and his sister had left Germany for Scotland as young adults and it seemed they had closed a chapter of their lives, demonstrated most powerfully by the fact that they never spoke to each other in their native tongue. Though they had lived through the war in Nazi Germany, they never, ever, discussed it in front of us.

Very occasionally, I would hear my father and his sister talk of the parents they called Vati and Mutti (dad and mum). They spoke in tones of great warmth and affection that are typical of children for whom the death of a loved parent means endless bereavement.

I was 50 years old when, one April evening, the German grandfather who had died the year before I was born came unbidden into my house under a different guise. A casual search on the computer for something else brought the following words up on the screen:

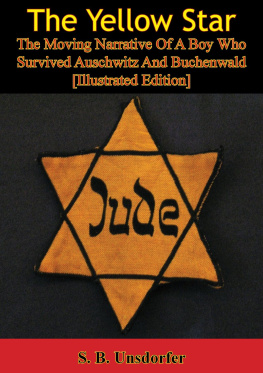

SS-Hauptsturmfhrer Karl Niemann crimes against humanity use of slave labour.

My dad had told me that he thought his father was only a pen-pusher. And that was true. It was just that for seven years his pen pushed tens of thousands of half-starved concentration camp inmates from Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, Dachau and other places of shocking notoriety into work.

Eleven million people perished in the Holocaust. Most of them slept (and many died) in the bunk beds that my grandfather had responsibility for manufacturing. He regularly visited concentration camps as part of his work. He saw the skeletal figures and must surely have witnessed torture and brutality. Yet for ten years he carried on working for the SS regardless, taking home his wages, tending his garden, reinventing himself in the evenings as a family man.

A Berlin exhibition in 2013 named Karl Niemann as a Schreibtischtter, a desk-bound criminal. I came to discover that he was anything but desk-bound. And while the nature of his work was unquestionably criminal, my research led to a man whose actions and motivations were far more complex and even contradictory than I could ever have expected.

This book tries to follow and explain the life of my SS grand-father. But much more than that, it tells, through the voices of children of that time, an astonishing story of a family living through some of the most cataclysmic events of the twentieth century.

My father and his surviving brother broke their long silence for me, to give eyewitness testimonies. They had been mischief-making innocents who saw plenty and understood little. Whatever the sins of their father, I would not wish their experiences on anyone.

I was born into a land without mangoes. No pomegranates, pawpaws, kiwi fruits or clementines. No Lindt, Ferrero-Roch, or panettone. Scotland is a country whose umbilical cord is attached to a bag of sugar. Back in the 1960s, the choice of exotic delights from abroad was far more limited than it is today. But our family had its own private route to sweet ecstasy.

Every December, a taste of Germany arrived in a big cardboard box stamped with unpronounceable words of improbable length. The great opening drew out gingerbread biscuits dipped in thick white and dark chocolate. There was still more chocolate little latticed affairs coated in crunchy multi-coloured beads. Best of all was the chocolate-covered marzipan, wrapped in red tin foil, and then wrapped again in cellophane, as if to protect its special qualities. From Lbeck, said my dad, pronouncing the first syllable eeooo as if it was shooting off a ski slope. The finest marzipan in the world. And it was too the first bite releasing a delicate flavour of almonds. Then there was what my dad called sshhtollen, an icing-dusted cake with a generous layer of marzipan and a fruity thick dough that you could squeeze with your tongue against the roof of your mouth. Hark the German angels sing.

Some of my earliest experiences introduced me to sounds from my fathers homeland. He entered into the Christmas spirit, uttering four words that I came to know if not quite understand. He rolled his eyes, began conducting an invisible choir with both index fingers and half spoke, half incanted the words Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht, his face a picture of reverential bliss.

My happiest moments as a small child came when he would once in a while prop me up on his knees facing him, holding me by the armpits. He began to sing a German nursery rhyme that appeared to have a plot like that of Humpty Dumpty, but with the bonus of a spine-tingling ending. Hoppe, hoppe Reiter, wenn er fllt dann schreit er (Bumpety, bump, rider, when he falls, he cries). It was a jiggling journey full of mounting suspense, for the hapless horseman does not fall off his horse and into a ditch until the very end. My dad would bounce me on his knee, his rhythmic chanting in that strange tongue, foreign and familiar, quickening until the moment when he shouted Plumpfs! and dropped me between his knees so that my bottom kissed the ground. Then he would always lift me up laughing. Do it again, Daddy. Again. But he never would. I saw his broad smile fade, the enchantment vanish.

For the most part, Germany to us children meant the side that had lost the war. Action films played out on our black and white television every Saturday night. The Battle of Britain, The Great Escape, Where Eagles Dare, The Dam Busters My dad seemed to watch willingly enough, eyes fixed to the screen, hand reaching into a bowl of peanuts. He dipped again, and again, and again. At the end of every film he would give the same pronouncement. If it was a British-made film, he would say: Those bad Germans again. If it was American, he would lean back into the settee and declare: Vot a load of utter rubbish.

If a programme about the First World War came on, my dad would often be prompted to remark: Vati got the Iron Cross. The corners of his by now tight-lipped mouth would curl downwards and he would pull out his left breast pocket between his thumb and forefinger, looking down as if he half expected to see the metal badge on his chest. What did he get it for? I asked hopefully. He shrugged. I dont know. He didnt talk about it.

A war-obsessed boy, I was disappointed with my parents, who had lived through the Second World War, without it apparently leaving much trace on them. My mum had clearly had a dull, dull war, a small child crouching in the stairwell of her Glasgow tenement every night, waiting for the bombs to come, though she had been too young to remember when they did. Her father was Wee Willie Coulter, just 5 feet 3 inches tall, wearing a pork-pie hat and a long coat that came down to his shins and made him look like a KGB agent. Our Scottish grandfather hadnt even fought, but had been in a reserved occupation, keeping the Glasgow buses going with his spanner. My mum seemed to think he had been in the Home Guard but she couldnt be sure what hed done to defend his country.

Three years older than my mother, my dad would divulge only one brief memory of his life in Berlin, and would do so with such Pavlovian predictability that I was sure it was the only memory he possessed; the single recollection of a very small boy. He spoke of watching pieces of tin foil raining down on the city a ruse by the Allied planes overhead to disrupt German radar, he said. He also told me that his family had escaped to the Alps. His father had been a banker he had taught his sons to light the tips of fresh pine needles to fill the house with a sweet aroma.