Contents

Guide

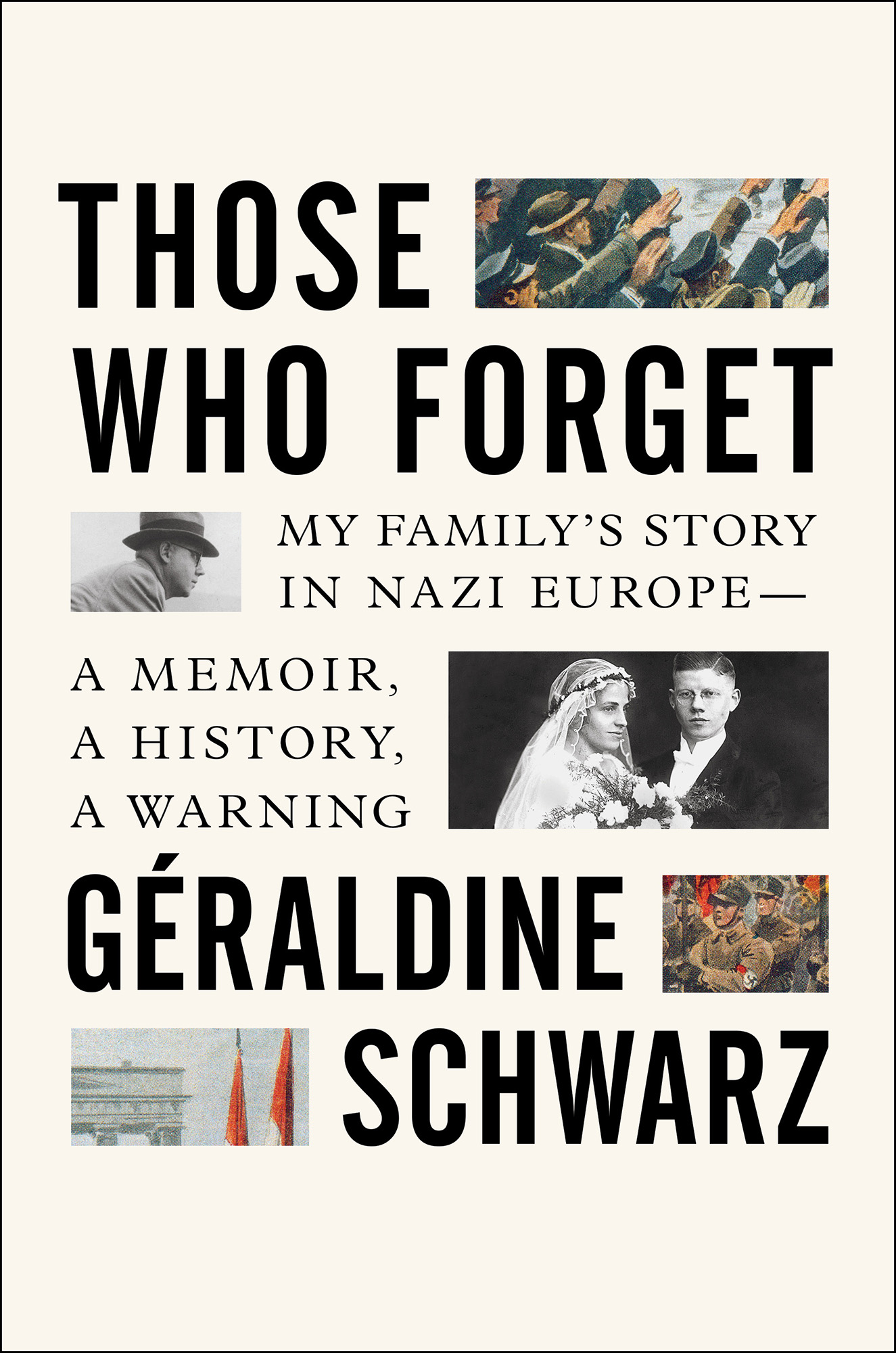

Scribner

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2017 by Editions Flammarion, Paris

Originally published in France in 2017 by Editions Flammarion as Les Amnsiques

English translation copyright 2020 by Laura Marris

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition May 2020

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Kyle Kabel

Jacket design by Tristan Offit

Jacket artwork: Painting by Hirarchivum Press/Alamy Stock Photo; Photographs Courtesy of the Author

Photographs courtesy of the Schwarz family, except p. , courtesy of Lotte Kramer

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020004934

ISBN 978-1-5011-9908-0

ISBN 978-1-5011-9910-3 (ebook)

Note to Readers: Certain names and characteristics have been changed.

Lines from the translation of Paul Celans Death Fugue copyright 2005 by Paul Celan and Jerome Rothenberg. From Paul Celan: Selections, University of California Press. Reprinted with permission of the translator.

Silence by Lotte Kramer. First published in Great Britain by Rialto, No. 80, Spring-Summer 2014. Published by Rockingham Press in 2015 in New and Collected Poems by Lotte Kramer. Copyright 2014, 2015 by Lotte Kramer.

To my parents

Everything that needs to be said has already been said. But since no one is listening, everything must be said again.

Andr Gide

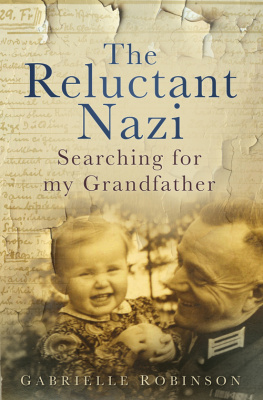

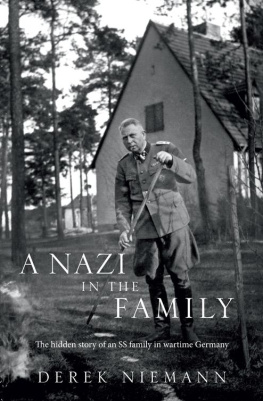

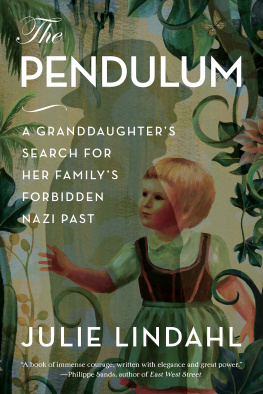

I To Be or Not to Be a Nazi

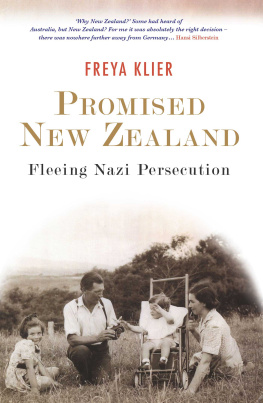

I wasnt particularly destined to take an interest in Nazis. My fathers parents were neither on the victims nor the executioners side. They didnt distinguish themselves with acts of bravery, but neither did they commit the sin of excess zeal. They were simply Mitlufer, people who followed the current. Simply, in the sense that their attitude was shared by the majority of the German people, an accumulation of little blindnesses and small acts of cowardice that, when combined, created the necessary conditions for the worst state-orchestrated crimes known to humanity. For many years after the defeat, my grandparents, like most Germans, lacked the hindsight to realize that though the impact of each Mitlufer was tiny on an individual level, it had a cumulative effect, since without their participation, Hitler would not have been able to commit crimes of such magnitude. The Fhrer himself sensed this and regularly took the measure of his people to see how far he could go, all the while inundating them with Nazi and anti-Semitic propaganda. The first massive deportation of Jews in Germany, which would test the general populations threshold of acceptance, took place in the exact same region where my grandparents lived. In October 1940, more than 6,500 Jews from the southwest of the country were deported to the Gurs camp in the south of France. To accustom their citizens to such a spectacle, German forces of law and order attempted to save face by avoiding violence and commissioning passenger carsnot the freight trains that were later used. But the Nazis wanted to know how much the people would be able to stomach. They didnt hesitate to operate in broad daylight, herding hundreds of Jews through the city center to reach the train station, with their heavy suitcases, their children in tears, and their exhausted elderlyall of this right before the eyes of apathetic citizens who were incapable of exercising their humanity. The next day, the Gauleiter (district chiefs) proudly announced to Berlin that their region was the first in Germany to be judenrein (purified of Jews). The Fhrer must have rejoiced to be so well understood by his people: the time was ripe for following.

One episode, unfortunately one of the few, proved that the population had not been as powerless as it hoped to appear after the war. In 1941, protests by citizens and Catholic and Protestant bishops across Germany succeeded in disrupting the planned extermination of physically and mentally disabled people, or those judged as such, that had been ordered by Adolf Hitler in an effort to purge the Aryan race of life unworthy of life. Although this secret operation, called Aktion T4, was in full swing, having already gassed 70,000 people in specialized centers in Germany and Austria, Hitler relented in the face of public indignation and called off his plan before it could be completed. The Fhrer understood the risk he would run if the population perceived him as too overtly cruel. This was also one of the reasons the Third Reich expended an insane amount of energy organizing an extremely complex and expensive system to transport Jews from all over Europe to isolated camps in Poland, where they were murdered far from the eyes of their fellow citizens.

But in the aftermath of the war, no one, or almost no one, in Germany asked themselves what might have happened if the majority of citizens had not followed the current, but instead turned against a politics that had revealed relatively early its intention to crush human dignity under its heel. Going along with these politics, like my grandpa, my opa did, was so widespread that this crime was mitigated by its banality, even in the eyes of the Allied forces who got it into their heads to denazify Germany. After their victory, Americans, French, British, and Soviets divided the country and Berlin into four zones of occupation where each engaged in eradicating the Nazi elements of society with the help of German arbitration hearings. They determined four degrees of implication in Nazi crimes, the first three of which theoretically justified the opening of a judicial investigation: the major offenders (Hauptschuldige); the offenders (Belastete); the lesser offenders (Minderbelastete); and the followers (Mitlufer). According to the official definition, this last term designated those who did not participate more than nominally in National Socialism, in particular the members of the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) who only went so far as to pay membership fees and attend required meetings.

In reality, among the 69 million inhabitants who lived within the borders of the Reich in 1937, the number of Mitlufer surpassed the 8 million members of the NSDAP. Millions of others had joined affiliated organizations, and still more had cheered National Socialism without belonging to a Nazi organization. For example, my grandmother, who was not an NSDAP member, was more devoted to Adolf Hitler than my grandfather, who was an official party member. But the Allies didnt have time to examine such nuances. They already had enough to handle with the offenders, both major and lesser: the multitude of high-level officials who had given criminal orders within the bureaucratic labyrinth of the Third Reich, and the many who had executed those orders, oftentimes with an infamous zeal.