First published in

Great Britain in 2010

By Pen and Sword Aviation

An imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Jon Sutherland and Diane Canwell 2010

9781783031849

The right of Jon Sutherland and Diane Canwell to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13pt Palatino

by Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by CPI

Pen and Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen and Sword Aviation, Pen and Sword Maritime, Pen and Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

T he authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of a number of people who lived along the east coast of England during the Second World War. Notably we should like to thank Brian Provan of Hellesdon, Clyte Venvell from Knapton in Norfolk, Patricia Fogarty of Norwich, Geoff Parker of Great Yarmouth, E. Martin of Lowestoft, George Woods of Halesworth, Paul Rush of Norwich, Patricia Lilley of Great Yarmouth, Eileen Robinson (ne Turner) of Lowestoft, Rosemary Hodgkin (ne Whitehand) of Gorleston, Gary Brown of Gorleston, Keith Farman of Gorleston, Richard Kerridge of Bradwell near Great Yarmouth, Ivy Wright of Gorleston, Mary Dove of Bradwell and Graham New, whose father was in the police force in Great Yarmouth during the war. Special thanks go to Norman Bacon, formerly of Norwich and now living in Ipswich, for sharing his lifetime research on the Norwich bombings. Also, many thanks to Stephen Pullinger, the chief reporter for the Eastern Daily Press , Great Yarmouth, and to Matthew Gudgin of BBC Radio Norfolk for their help.

Introduction

T he Nore is actually a sandbank, sitting in the mouth of the Thames Estuary and close to the Isle of Sheppey. It is considered to be the point where the River Thames becomes the North Sea. For centuries the sandbank has been a major hazard to shipping. Unsurprisingly it became the site of the worlds first lightship in 1732.

The Nore is also a term that is used to describe the anchorage at the mouth of the River Medway, used for centuries by the Royal Navy. Indeed, so important was this entrance to Britains capital via the River Thames that a Nore Command was established, later with subordinate commands at stations such as Ramsgate and Great Yarmouth.

By the Second World War Nore Command, now stretching from Bridlington in the north to Ramsgate and the beginning of the Dover Strait in the south, had assumed vital importance. The command would protect the coastal shipping routes along the east of England. It would act as a shield against German seaborne invasion. It would also be the scene of vicious and prolonged enemy air raids along the length and breadth of Britains eastern flank. Ultimately, as the tide turned against Germany and her allies, the east of England would resemble a vast aircraft carrier and a staging-post, as Allied armies prepared to liberate occupied western Europe.

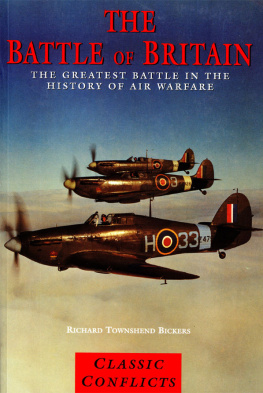

In the dark days of 1940, when invasion seemed only days away and the German Luftwaffe pummelled the south coast of England, the RAFs airfields and London itself, the east coast lay vulnerable and unprotected. East Anglias defences were hopelessly under strength in terms of aircraft, searchlights, anti-aircraft guns and ground units to counter any potential invasion. In 1939 the Thames Estuary was undoubtedly the worlds busiest waterway.

Indeed, the maritime tradition dominated the whole of the east coast, and this was despite the economic crisis that had taken place earlier in the 1930s. This was before there was any major decline in the importance of east coast seaports, ship building and, of course, the fishing industry.

The Commander-in-Chief of Nore Command, who at the outbreak of the war was Admiral Sir Henry J. Studholme Brownrigg, was responsible for the whole of the North Sea and the Dover Strait, between the east coast and the low countries of continental Europe. His headquarters was at Chatham and known as HMS Pembroke . He had four sub-commands, each under the command of a Flag Officer-in-Charge (FOIC). Each of these men had the rank of either rear admiral or vice-admiral.

Dover was commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir Bertram Home Ramsay, who had been in the Royal Navy since 1898. He knew the Dover Strait and the Belgian coast like the back of his hand. He had been brought back out of retirement by Winston Churchill and promoted to vice-admiral on 24 August 1939. He would protect against German raiders and enemy cross-channel traffic, and attempt to clear the Straits of Dover of enemy submarines. At the Nore itself, Rear Admiral Hugh Richard Marrack, another veteran of the Great War, was in command. FOIC London was Rear Admiral Edward Courtney Boyle, who had won the Victoria Cross as a submarine commander in 1915, and Rear Admiral Charles Frederick Harris was FOIC of Harwich Sub-command.

As late as April 1937, north of London saw just two fighter groups, Nos 11 and 12, covering the whole of north Essex and the remainder of East Anglia. Supporting the fighters was No. 2 Anti-aircraft Division, which had been formed in December 1936. It was supported by the 1st Anti-aircraft Division, centring on London. On paper the 1st Division would need 1,000 searchlights, but it only had 120 of them. It was armed with 3 in. naval guns, which were woefully inadequate and of First World War vintage.

The Committee of Imperial Defence looked at vital points along the East Anglian coast in April 1937 and identified an immediate requirement for 300 Bofors guns. They identified what was known as Vital Points; most were oil depots or power stations at Kings Lynn, Ipswich and Norwich. A scheme was set up, and for the princely sum of 2 per year civilians would be attracted to the National Defence Battery, and they would defend their own places of work. But even this was considered to be too expensive a scheme. By late 1937 it was decided to increase the production of the Bofors guns. It was hoped that a twin-barrelled 2-pdr would come into production within the next eighteen months and that the 3 in. naval guns would be passed on to the Army or the Navy. By January 1938 No. 2 Anti-aircraft Division had less than fifty per cent of its required manpower.

Prior to the outbreak of the war, in the summer of 1938, reinforcements arrived in the shape of Spitfires at Duxford, but it would take time for them to become operational. As the Munich crisis developed, Territorial units were mobilised and sent off to establish searchlight and anti-aircraft positions around East Anglia.