Other books written by John Frayn Turner

Service Most Silent

VCs of the Royal Navy

Prisoner at Large

Hovering Angels

Periscope Patrol

Invasion 44

VCs of the Air

Battle Stations

Highly Explosive

The Blinding Flash

VCs of the Army

A Girl Called Johnnie

Famous Air Battles

Fight for the Sky (with Douglas Bader)

Destination Berchtesgaden

British Aircraft of World War 2

Famous Flights

The Bader Wing

The Yanks Are Coming

Frank Sinatra

The Bader Tapes

The Good Spy Guide

Rupert Brooke The Splendour and the Pain

Douglas Bader

Heroic Flights

VCs of the Second World War

The Life and Selected Works of Rupert Brooke

Awards of the George Cross

First published by Airlife in 1995

Reprinted in this format in 2010 by

Pen and Sword Aviation

An imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John Frayn Turner 1998, 2010

9781783034079

The right of John Frayn Turner to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 10.5/13pt Palatino

by Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by CPI UK

Pen and Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen and Sword Aviation, Pen and Sword Maritime, Pen and Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

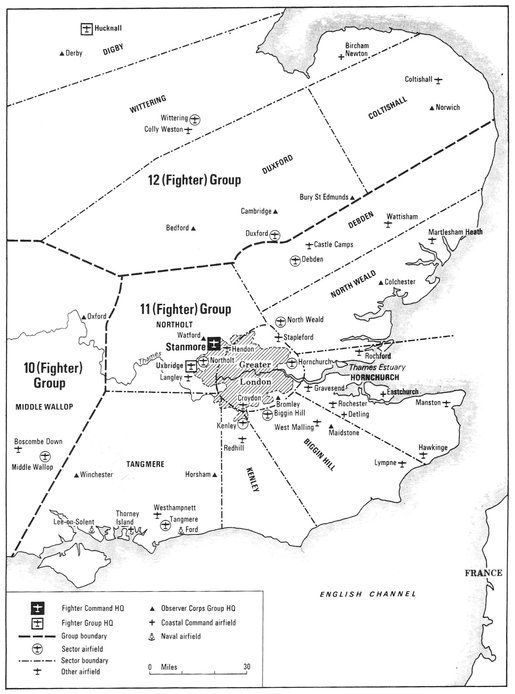

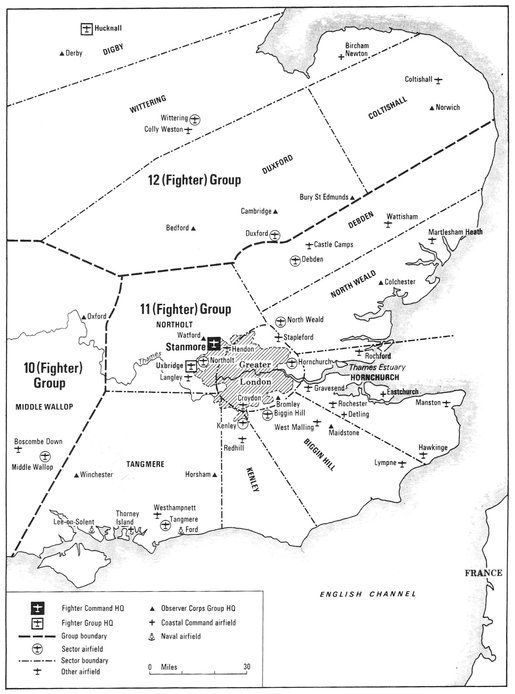

I n a conflict on such an epic scale as the Battle of Britain, it is clearly impossible to cover every single sortie of every aircraft. I have sought to convey the overall story and also to focus on a few of the pilots and squadrons. These represent the achievements of The Few as a whole. I have chosen to deal in detail with 12 Group because I feel that its activities have not hitherto been put into the perspective of the entire battle. Of course I appreciate that 11 Group bore the brunt of the air fighting and acknowledge it freely and fully in the text. But no matter whether the participating pilots were in 10, 11 or 12 Groups, they all contributed to the eventual victory and so did their counterparts on the ground, both men and women.

In addition to the list of general references, I would like to acknowledge, with sincere thanks, first-hand or other help from the following: Peter Townsend, Johnnie Johnson, Hugh Dundas, Alan Deere, Douglas Bader, Geoffrey Page, Tom Gleave, Richard Hillary, John Hannah, John Cunningham, Peter Brothers, E.S. Marrs, then P/O Stevenson, R.F. Hamlyn, Joan Pearson, Felicity Hanbury, then A.C.W. Cooper, then S/O Petters, Joan Hearn, R.S. Gilmour, John Sample, Gilbert Dalton, Richard Hough, Denis Richards, David Masters, J.M. Spaight, Jim Coates and Winston Churchill. Part of the final chapter is based on material in the official history Royal Air Force 1939 45 Volume 1 by Denis Richards.

CHAPTER ONE

Hurricane and Spitfire Prelude

T he Battle of Britain was one of the crucial conflicts in the history of civilization. It started officially on 10 July 1940 and ended on 31 October 1940. But the story goes back to the birth of the two famous fighters the Hurricane and Spitfire. For without them there could have been no battle at all. The date was 1933: only six years before the war and seven before the Battle of Britain. At that time, the Royal Air Force had just thirteen fighter squadrons. Eight were equipped with Bristol Bulldogs, three with Hawker Furies and two with Hawker Demons. All were biplanes, with fixed propellers and undercarriages.

The idea of the Hurricane was born in October 1933 when its designer, Sydney Camm, submitted a first design to the Air Ministry. By December 1934 a wooden mock-up of the single-seat, highspeed fighter monoplane existed and in the following August the first prototype was underway. On 6 November 1935, Flight Lieutenant P.W.S. Bulman, chief test pilot of Hawkers at the time, took off on the first flight. The small silver monoplane climbed off a grass strip that was surrounded by the banked curves of the famous Brooklands racing car track.

Germany was rearming rapidly and to many men like Winston Churchill it seemed that time was already getting desperately short. With the maiden flight of the Hurricane, a sense of urgency was beginning to be instilled into the British government, too. All went well throughout the early tests and on 7 February 1936 Bulman was able to recommend the fighter as being ready for evaluation by the Royal Air Force. This came a mere three months after that first flight, a tribute to Sydney Camms design. Two other pilots who participated in some of the early experimental work were Philip Lucas and John Hindmarsh.

On 3 June 1936 three years before the war Hawkers accepted a contract to construct 600 aircraft. Within a week they had issued fuselage manufacturing drawings. Soon after this, the Hurricane received official approval from the Air Ministry. Never before had such a big order been awarded in peacetime Britain. It proved in retrospect to have been a historic turning-point in the outcome of the Battle of Britain.

In the course of production, Hawkers had to make a number of modifications. As a result of rigorous tests of the original prototype by the RAF, several snags had appeared. Not surprisingly, in a comparatively revolutionary design. During the 1937 flights simulating high-speed combat duties, canopies of the closed cockpit were actually lost on five occasions, but the trouble was eventually cured.

The first production model of the Hurricane, with a Merlin II engine, made its maiden flight on 12 October 1937: only two years before the war now. Seven weeks later, seven aircraft were in the air. The Merlin II engine change put the overall production programme back. Even so, the first four Hurricanes for the RAF reached 111 Squadron at Northolt during that December and a dozen more came along in January and February 1938.

The British public became dramatically aware of the new super-fighter when Squadron Leader J. Gillan, Commanding Officer of III Squadron, took off on 10 February 1938 from Turnhouse, Edinburgh, just after five oclock on a gloomy and wild winter dusk. Gillan ascended to an altitude of 17,000 feet and flew over the clouds without the aid of oxygen. An 80-mph wind whistled him southwards at a great speed for those days. About 40 minutes later, he dipped his Hurricane into a dive, registering an air-speed of 380 mph. Once below the clouds, he made out Northolt aerodrome in the early evening darkness startled at the realisation that the ground-speed was likely to be in the region of 450 mph. The actual statistics for the flight were as follows: 327 miles from Turnhouse to Northolt in 48 minutes at an average ground-speed of 408.75 mph.