Also by Stephen Alter:

NONFICTION

All the Way to Heaven: An American Boyhood in the Himalayas

Amritsar to Lahore: A Journey Across the India-Pakistan Border

Sacred Waters: A Pilgrimage Up the Ganges River to the Source of Hindu Culture

Elephas Maximus: A Portrait of the Indian Elephant

Fantasies of a Bollywood Love Thief: Inside the World of Indian Moviemaking

FICTION

Neglected Lives

Silk and Steel

The Godchild

Renuka

Aripan and Other Stories

Aranyani

The Phantom Isles

Ghost Letters

Copyright 2014 by Stephen Alter

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

First North American Edition 2015

Photograph of Flag Hill courtesy of Aaron Alter

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

Visit the authors site at stephenalter.net

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Erin Seaward-Hiatt

Cover photo: Coni Hrler

ISBN: 978-1-62872-510-0

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62872-542-1

Printed in the United States of America

For Ameeta

As we look at the Himalaya from such distance that we can see things whole and in their just proportion, the pain and disorder, squalor and strife, vanish into insignificance. We know that they are there, and we know that they are real. But we know also that more important, and just as real, is the Power which out of evil is ever making good to come . This is the true secret of the Himalaya.

Francis Younghusband

Writing is, I suppose, a superstitious way of keeping the horror at bay, of keeping the evil outside.

Paul Bowles

The face of the landscape is a mask

Of bone and iron lines where time

Has plowed its character.

I look and look to read a sign,

Through errors of light and eyes of water

Beneath the lands will, of a fear

And the memory of a struggle,

As man behind his mask still wears a child.

Stephen Spender

Contents

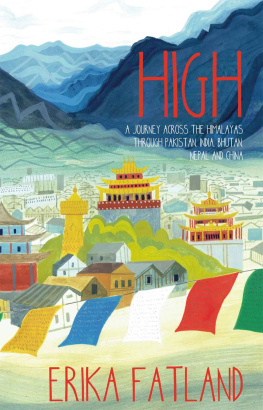

A Note on the Himalayas

The pronunciation and spelling of the word Himalayas has been a matter of dispute from the time it was first translated into English. In Sanskrit Hem or Him means snow and alaya denotes the place of. When I was a boy, we were taught to stress the second syllable ( Himaalaya ), rather than swallowing the vowel ( Himlaya) as many people do. We believed this was the correct pronunciation, though it differed from the original Sanskrit. As for spelling, many purists assert that Himalaya, without the s , is more accurate and gives the mountains a singular grandeur. Common usage has devolved into the plural form that I have chosen for this book. My purpose is simply to avoid confusion among readers who may not be aware of the arcane nuances of this debate. In the end, of course, no matter how we transliterate their name, the Himalayas will always rise above the perverse inadequacies of language.

Becoming a Mountain

FLAG HILL

Distant Prayers

If the red slayer think he slays,

Or if the slain think he is slain,

They know not well the subtle ways

I keep, and pass, and turn again.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Birthright

The true face of the mountain remains invisible, though its southern aspect presents a familiar profile. Two corniced summits, with a broad intervening ridge draped in snow, fall away more than ten thousand feet into the valley below. From certain angles and at certain times of day, just behind the eastern peak, a pale, indistinct shadow becomes visible, the hint of something else beyond. This is the third summit, hidden but higher than the other two by a couple hundred feet. During the dry seasonslate fall and early springdark gray shapes begin to appear on the mountain. Avalanches have carried away the snow, and ice has melted, revealing the underlying strata of rock tilted skyward by interminable forces of geology.

I have looked at this mountain all my life, sometimes at dawn, or midday, or dusk, even by moonlight, yet there is no way that I can accurately describe its presence, whether I use poetry or the contentious languages of religion and science. Both the mountains myths and its natural history have an elusive, enigmatic quality. I have sketched it in pencil, pen, and watercolor, but each time I have failed to express a convincing vision of what this mountain represents. Over the years, I must have photographed those twin summits several hundred times, but none of my camera images seems to capture anything more than a faint suggestion of the mountain, mere ghosts of light. I know that it stands there, but what it means is beyond my comprehension. Yet, constantly, I see myself in this mountain and feel a part of its immensity, as well as a greater wholeness that contains us all in the infinite, intimate bonds of eternity.

At the beginning of October 2012, we buried my fathers ashes in the cemetery on the north side of Landour ridge, facing the Himalayas. He and my mother had chosen our family plot years before. Two of my uncles were already buried there, on a terrace overshadowed with deodar trees. My fathers grave looks out upon a snow-covered mountain called Bandarpunch, the monkeys tail, which takes its name from an episode in the Ramayana . This is the most prominent peak we see from our home in Mussoorie, a broad massif with twin summits rising 20,722 feet above sea level.

When my father died, on June 19, 2011, I was attempting to climb Bandarpunch. Our expedition, comprised mostly of staff from Woodstock School, was organized by the Nehru Institute of Mountaineering (NIM), in Uttarkashi. Before I reached base camp, a wireless message came in from my wife, Ameeta, patched through on the radio at NIM. My fathers condition had suddenly grown worse. For a year and a half he had struggled with skin cancer, which had spread to his throat and other parts of his body. We knew that he was dying, but I didnt expect it would happen so soon.

During our last conversation, on the morning I left for Bandarpunch, my father could barely speak, though he told me to be careful on the mountain. He was worried about my safety, even as he faced his own mortality. We talked for half an hour over a poor connection following an early monsoon storm, the line rasping with static. My mother translated his hoarse words through their speakerphone. A month before, I had traveled back with them to their home in Wooster, Ohio, after my father made a final visit to Mussoorie. Dad joked that his cancer was a result of the Indian sun and the consequences of having white skin. He reminded me to take sunscreen with me on the expedition.