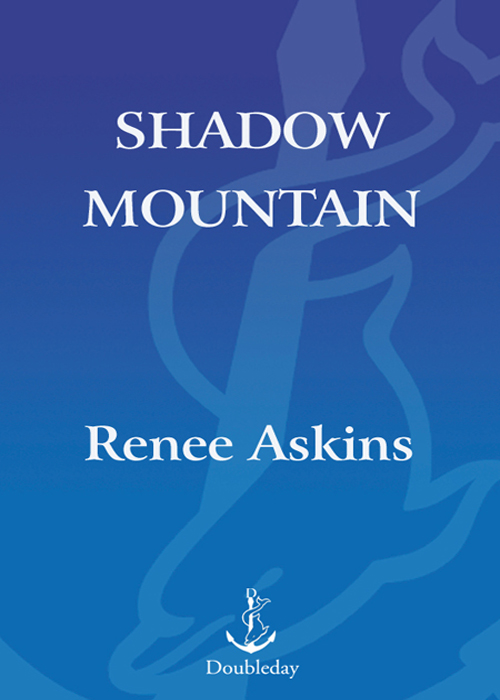

Shadow Mountain

A Memoir of Wolves,

a Woman, and the Wild

Rene Askins

DOUBLEDAY

New York London Toronto Sydney Auckland

Contents

For Siena Aurora Askins Rush

and

For Natasha

In all her mystery and incarnations

Whatever you do will be insignificant

and it is very important that you do it.

MOHANDAS GANDHI

Prologue

D URING THE YEARS of writing Shadow Mountain people would ask me, What is your book about? I found that each time I would answer differently depending upon what chapter I was working on, or my mood that moment. This book is about... keeping a promise, living a passion, loving an animal, not giving up, hope, living from hope to hope, heartbreak, incandescent joy, wolves, wildness lost, wildness found, wildness within, healing, wounding, restoring, common experience, uncommon experience, a place called Shadow Mountain, a wolf named Natasha. I now realize that all these were true, each a vital ingredient of the story of Shadow Mountain.

With many undertakings, especially those that are drawn out over years and involve self-examination, one finds that the person who began the journey is someone quite different from the one completing it. When I crested Togwotee Pass in 1981, glimpsing the panorama of Jackson Hole and the Tetons in the swirling mists of an early winter snowstorm, I wondered if the restoration of wolves to Yellowstone would take a full year. Fourteen years later I learned the answer: yesand thirteen more. Its rather odd to wake up one morning and realize that nearly a decade and a half has slipped by in the pursuit of a passion, one that you never intended to become your mission, or even your career, certainly not your identity. Likewise, when I began writing this book I thought it would be simple; I would just tell the story of returning wolves to Yellowstone, A to Z, but I soon realized I was uninterested in chronicling the Kafkaesque drama of meetings, memos, political wrangling, and philanthropy that I had lived for so long. I was far more interested in why, than I was in just who, what, and when. How, after all, had I come to this; or had it come to me? Did those years make a difference? Were they worth the cost and compromises?

The thread of a life is not stretched taut between two points. It twists in unexpected and mysterious ways, not so much weavingas poets would have us believeas snarling and catching, creating the tangles and knots which hold our stories and the keys to our understanding them. I at first thought this process would lead me to revelations that would be laid out like bright Easter eggs here and there along the path of my history. It turned out that I didnt discover the answers to my questions by systematically sleuthing through the calendar of my life. Rather, I found the truth buried beneath the surface of the storynot the intellectual, rational, ordered truth, but the deep, resonant, singular truth of my heart.

I had a fantasy that followed me through many of the years I worked on Yellowstone wolf recoverywhen it was over, when I was released from this frenetic, consuming mission, I would send a letter home to all the people I loved explaining everything: why I had been so silent, so absent, so out of touch, gone for so long; why calls and letters had gone unanswered, baby presents unsent, weddings unattended, and why there had been times I wasnt there to listen, to comfort, to congratulate. I would explain that I had been swept away by events that flowed from a promise made to an animal I loved, and it had been a long, long journey back. It wasnt that I needed to apologize, rather I needed to tell my story: I needed to reconcile who I had been before the journey with who I had become during it. It was a need to express that a life lived devoted to the truth of ones heart reaches beyond either/or choices, that there are circumstances in which we must sacrifice some of now for later, trusting that everything has a right time, meaning, and place.

So Shadow Mountain is what came of my wonderings and wanderings among wolves and word these last twenty years. This book contains the stories of my travels, written with a compulsion to discover, through a maze of memories, the meaning of these many years. Written from the truth of my heart, it is my letter home.

Rene Askins

Wilson, Wyoming

February 5, 2002

One

On this cold night

winters last rally

rakes across the fledgling breast

of spring like claws. The last white bear

turns, hungering,

northward.

We put on layers of sweaters again

and light a circle of lamps

deep in the heart of the house. But

we are restless, keep listening.

You are the first to get up.

You pace a few silent steps

then go. Upstairs I find you

perched at the window,

an early stork

staring from the slender chimney

of your bones down

at icy slivers of teeth

slicing into tender garden growth.

Without thinking why

we gather the afghans

and carefully fold our long limbs

down into them.

With a soft ritual clicking of bills,

necks twining, wings rising,

we begin

the ancient migration

back to the place

of our birth.

MARCIA CASEY, Storks

M Y FIRST MEMORIESare of meadows. Evening meadows, when the suns honey-warm rays turned the long grasses and birch borders into an enchanted and radiant secret. It is the light I mostly remember, when the dark was seducing the day and the shadows would flicker and splinter in a spectacle of courtship. It was the hour of whimsy and expectation. Perhaps it was the melon light that beckoned the deer. They emerged like druids from the forests, miragelike in the tall shimmering grass, unable to resist those last lingering moments of summer sunlight to warm their shadow-cooled backs.

My mother would count them. Two, three, four, ten, twenty-six, twenty-seven, twenty-eight. My older sister Robin and I would listen and watch, two small daughters perched beside their mother on the liver-colored seat of a plump black Volkswagen Bug. There was no television in our remote cottage in the Thunder Bay State Forest of northern Michigan, and my father had to travel for his work, leaving my mother in the silence of those white pine forests for days at a time.

Thats how the summer evenings of my early childhood passed, our Volkswagen parked alongside some meadow, with its nose edged into the tall summer grass like a huge Lab sniffing the dirt, with my mama counting the deer. Its also how I learned to count, but for years I would be confused about what numbers really followed others because my mothers voice would drift off at fourteen or thirty-seven, like the sun slipping behind a darkened cloud into some secret shadowed place that concealed the loneliness of a young mother, and then suddenly her voice would reemerge brilliant and warm on twenty-six or forty-three. I doubt that it mattered to her how many deer there were, the numbers were only a mantra to give order to the loneliness, to arrange an eternal evening according to a knowable rhythm. Occasionally she would remark on how large a fawn had gotten, or on the limp of a doe, but mostly she would just count, thirty-eight, thirty-nine, forty... and the light would fall and her voice would trail off and the deer would slip back into the shadows.