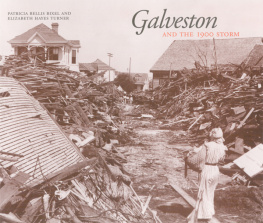

GALVESTON AND THE 1900 STORM

GALVESTON

AND THE 1900 STORM

Catastrophe and Catalyst

PATRICIA BELLIS BIXEL AND

ELIZABETH HAYES TURNER

University of Texas Press,

Austin

This book has been published with the assistance of a grant from the Galveston Historical Foundation and a challenge grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

COPYRIGHT 2000 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Sixth paperback printing, 2008

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

utpress.utexas.edu/about/book-permissions

DESIGN AND TYPOGRAPHY BY TERESA W. WINGFIELD

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Bixel, Patricia Bellis, 1956

Galveston and the 1900 storm : catastrophe and catalyst / Patricia Bellis Bixel and Elizabeth Hayes Turner.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-70884-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Galveston (Tex.)History20th century. 2. HurricanesTexasGalvestonHistory20th century. 3. FloodsTexasGalvestonHistory20th century. I. Turner, Elizabeth Hayes. II. Title.

F394.G2 B59 2000

976.4139dc21 99-087876

ISBN 978-0-292-75395-2 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-75396-9 (individual e-book)

For the victimsand survivorsof the 1900 Storm

SEPTEMBER 8, 1900SEPTEMBER 8, 2000

FOREWORD

This is the story of the death and resurrection of an American city. The advent of the twenty-first century marks the centennial of the nations worst recorded natural disaster, a devastating hurricane that has come to be known as the 1900 Storm. This occasion is an especially appropriate time for a detailed examination and interpretation of how the hurricane that destroyed Galveston, Texas, on September 8, 1900, brought about a political, gender, racial, and technological transformation. An island city located along the southeast coast of Texas, Galveston in 1900 had a population of almost thirty-eight thousand people. It was a cosmopolitan and economically vibrant locale, thanks in good part to its prominence as the states leading seaport. Yet the geographic features that helped sustain its economic lifeblood also provided the seeds of its destruction. Galveston stood approximately nine feet above sea level on a sandbar island that was prone to flooding. In September 1900 an intensifying tropical disturbance passed from the Caribbean into the Gulf of Mexico and sealed its doom.

Through many firsthand accounts, Patricia Bellis Bixel and Elizabeth Hayes Turner paint a terrifying picture of the hurricanes wrath. Survivors found safe haven in tall buildings as wind and water left the city in ruins. Approximately six thousand people died; thousands more were injured. Estimates of property losses ran as high as $30 million. Wreckage filled the citys streets; corpses and animal carcasses blanketed Galveston with a terrible stench and posed the serious threat of disease. In less than a day, the cataclysm had completely rent the communitys fabric. Following the storm, Galveston was put under martial law to restore order and counter looting. A Central Relief Committee consisting of Mayor Walter C. Jones and eight other civic leaders served to expedite the recovery. Readers of Galveston and the 1900 Storm will easily visualize the enormous burden resting on the shoulders of these men as they coordinated efforts to dispose of bodies, rebuild structures, and restore services. Their determination to restore their city was, fortunately, unfettered by partisan bickering.

The disaster brought Clara Barton, then head of the American National Red Cross, to Galveston. Highly respected nationally for her humanitarian efforts, she was a personal catalyst for recovery. Working within the confines of the prevailing male leadership of the city, Clara Barton and the Red Cross assumed responsibility for relief distribution. Although women would be denied the right to vote until 1920, Bartons presence inspired Galveston women to become substantially involved in the shaping of public policy. They assumed a leadership role by evaluating both the losses of their community and the needs of storm survivors. They organized the Womens Health Protective Association in 1901, which had a political agenda from its inception and involved itself in lobbying for adoption of sanitary regulations. Its focus was natural in light of Progressivisms emphasis on municipal housekeeping. Thereafter, it undertook other causes, such as reburying storm victims and promoting the commission form of local government. In 1912, women assumed a more militant stance toward the issue of suffrage and organized the Galveston Equal Suffrage Association.

Galvestons African American citizens did not fare as well as white women. In 1898, two years before the storm, Galveston blacks lost their most prominent leader with the death of Norris Wright Cuney, who had commanded the respect of the citys influential white powerbrokers. Immediately after the storm, Galvestons black citizensmany of whom had performed heroic rescueswere vilified in the local press as scavengers and looters or portrayed as lazy and childlike. Discriminatory practices in the distribution of relief supplies and donations also worked against African Americans, who received only what was left overif that. And, after 1900, blacks had little say in Galveston politics because the commission form of local government, adopted in 1901, required commissioners to be elected at large, thereby effectively depriving blacks of representation. African Americans refused to be passive victims, however, and protested their exclusion both through active lobbying before the commission and through newspaper editorials. In addition, thriving black businesses, churches, and schools gave black Galvestonians a means of achieving self-sufficiency and expressing their pride.

The commission form of government was generally effectiveeven if, as noted, it excluded Galvestons black population from political representation. The commission was a governing body composed of five men and represented a radical effort to reinvent local government. Before the storm, the city was governed through a traditional mayor and city council structure which in Galvestons case was characterized by gross inefficiency and political infighting. The commission, which included prominent Galveston businessmen, put the city on a firmer, more businesslike footing and enabled the city to cope better with the staggering debt incurred as a result of the storm and the ensuing recovery efforts.

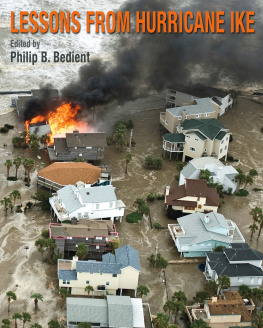

Protecting the city from future hurricanes required particularly drastic solutions, including the construction of a sea wall and the elevation of the citys gradetruly monumental undertakings. Constructed of concrete, the first sea wall segment was three miles long. After this first stage was completed in 1904, subsequent extensions of the wall ultimately ran its length to ten miles, with the final section completed in 1962. The grade raising, the initial portion of which was completed in 1911, entailed moving 16.3 million cubic yards of dredged fill and raising structures, streets, streetcar tracks, water mains, and gas lines. During the period it was under way, this civil engineering feat radically transformed the citys appearance: Galveston truly became a city on stilts, as it was called. Even by todays standards, the process of elevating over two thousand structures is a mind-boggling accomplishment.

Much scholarly work has been done on the Storm of 1900; Galveston and the 1900 Storm makes an important contribution to this area of research, for, unlike earlier works, it is a long-term study of the hurricane, its aftermath, and Galvestons subsequent transformation. From 1900 to 1915, the city was a nexus for certain Progressive Era activitiespublic health reforms, municipal housekeeping, and woman suffragethen sweeping the country. In the process of becoming a progressive southern city, Galveston served, as Bixel and Turner put it, as a laboratory of sorts, a testing ground for new ideas about government, society, and technology. The authors have made full use of available documentary sources. They mined the holdings of the Rosenberg Librarys Galveston and Texas History Center, which has the most significant archives of the 1900 Storm, as well as other research collections nationwide.

Next page