THE STORM OF THE CENTURY. Copyright 2015 by Al Roker Entertainment. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

A MAN PINNED UNDER THE WATER STRUGGLES TO FREE HIMSELF. Fifteen feet below the waters surface and the air he needs so badly, his thrashing body begins to weaken.

Big timbers, mercilessly heavyonly moments ago, they held up his houseare pressing him down. They hold him deep underwater. He cant move them. He begins to drown.

Knowing he has no chance, he stops struggling. The man tries to accept his fate.

Y et somehow when he comes to himself again, hes risen from the depths and broken the waters surface. Bobbing and kicking in a violently churning sea, he gasps for breath in the darkness, pelted by rain in a wind even louder than his gasps.

Two of the great house timbers that held him down have risen with him. They press him, one from each side. He clings to them.

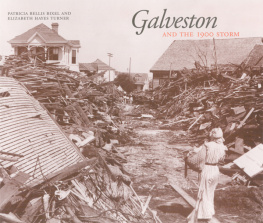

Hes alive. Its the night of September 8, 1900. And this isor wasGalveston, Texas.

The man is Isaac Cline. Gripping the timbers that nearly killed him, he surfs and circles randomly through a chaotic scene lit by flashes of lighting. There is no city. There is only this sea, its waves rising and falling as rooftops and treetops collapse into them. Objects of all kinds shoot from the swirling water and through the screaming wind: huge pieces of roof, doors, beds.

At every lightning flash, Cline scans the water. His pregnant wife and three daughters were with him in their second-story bedroom. He ducks projectiles in the air, dodges debris in the surf, tries with all his strength to stay above the rising water. Desperately seeking any sign of his beloved family, he fears the worst.

I saac Cline knows exactly whats happening. Hes a meteorologista weathermanand one of the countrys best. As he fights the wind, the water, and the flying debris, he understands that whats taking place tonight is something that he and other meteorologists of the United States Weather Bureau have long been certain could never occur here.

A hurricane, Cline has reassured the public, cant hurt Galveston, Texas.

Now Cline knows that this is a monstrous hurricane, and it has destroyed his city in only a few hours. He has been as wrong as its possible to be. All of the systems, all of the miracles enabled by the modern science of meteorology, have failed.

Theres no going back now. No way to correct the error. Galveston is gone.

W hat Isaac Cline cant know is that, more than a century later, this storm will remain not just the worst hurricane, but the worst natural disaster of any kind, ever to hit the United States: 10,000 or more lives lost in one night; higher winds and lower pressure than any previously recorded; damage estimated at nearly $20 million (more than $700 million in twenty-first-century money); a great city reduced overnight to miles of rubble. Adrift tonight on a surreal ocean of chaos where a city used to be, Cline can only go on scanning the dark maelstrom.

He can only pray for any glimpse of his wife and children. The best weatherman in America can only wish things had gone differently.

A SCORCHING END TO A HOT SUMMER: THATS WHAT EVERYBODY was saying. It was the first week of September in the grand turn-of-the-century year of 1900, and people in Galveston, Texas, were complaining about the heat.

Thats one reason little Mary Louise Bristol, seven years old, was looking forward to the weekend. At her mother Cassie Bristols boardinghouse, not far from the harbor on Galveston Bay, work went on despite the heat, just as it always didand just as work went on everywhere else all the time in bustling, steaming Galveston. This island city in the Gulf of Mexico, lying two miles off the Texas mainland, had become the most important port in the state, the foremost cotton-trading center in the world.

Gangs of hustling longshoremen, black, white, and Mexican, loaded and unloaded ships on the wharves on the bay. Bankers and lawyers made deals in their offices above the broad sidewalks of Avenue B, known as the Strand. Cassie Bristol, a widowed mother of four, ran her boardinghouse near the harbor in hopes of feeding and bettering her family. Along with nearly 40,000 others, they all played their parts in a booming citys busy life.

Mary Louise Bristol, known as Louise, was Cassies youngest. And Louise was the only member of her family who had any time for play. Sometimes she played alone. Sometimes she played with her friend Martha, who lived across the street.

But everybody else in the Bristol family was always busy with work. The girl knew her house wasnt only a home but also a living, and she knew her mother was a smart woman. Louises father, a seaman, had died at sea when Louise was just a baby, and Cassie, left alone with four children, rolled up her sleeves, took out a mortgage on the house, added a second floor, and started renting rooms. Cassie had a goal: keep her children from falling into poverty and disgrace while teaching them the ways of a genteel life.

That ambition made Cassies life a struggle. But it was a battle she was winning, thanks to constant work. Louises brothers were old enough to have jobs and to bring home their pay. Her sister Lois, fifteen, helped their mother at the boardinghouse.

And the Bristol place was especially busy this week. School was back in session after the summerLouise had just nervously started first grade on Mondayand every September, the house began filling to the brim with students of the University of Texas Medical School here in Galveston. Those young men were among Cassies most reliable customers. Soon theyd be swarming over the place, their trunks hauled in by horse-drawn wagon and humped inside by porters, their rooms assigned, their questions answered, their beds made, their food served. Louises mother was spending this week getting the place ready: cleaning and airing and washing and drying. Cooking and canning and stocking up on stores.

What the little girl most looked forward toas the endless work went on at home, and the heat of early September remained so oppressivewas the weekend. Hoping to forget about school, hoping for a change in the weather, Louise was looking forward to Saturday, when she could play.

S aturday, of course, would come. When it did, on the eighth of September, Louise, her mother, and the rest of the Bristol family would find themselves fighting gigantic volumes of ocean and wind beyond anything they could ever have imagined. Saturday would plunge them all, with all of their fellow Galvestonians, into a dark world of sheer horror.

A rnold Wolfram too was wilting out the end of summer with his fellow citizens in that first week of September. Wolfram would have seemed a staid enough, ordinary enough Galvestoniana member of the thriving German American community in that polyglot gulf town. At forty-three, Wolfram worked in a fruit and produce store, where he made sales and took inventory. He was married to the former Mary Schmidt. They had six children, with four still living at home.