J OHNNY, WHO MADE THE WORLD? THE S UNDAY SCHOOL TEACHER asked.

That was easy. The Cambria Iron Company! the boy replied.

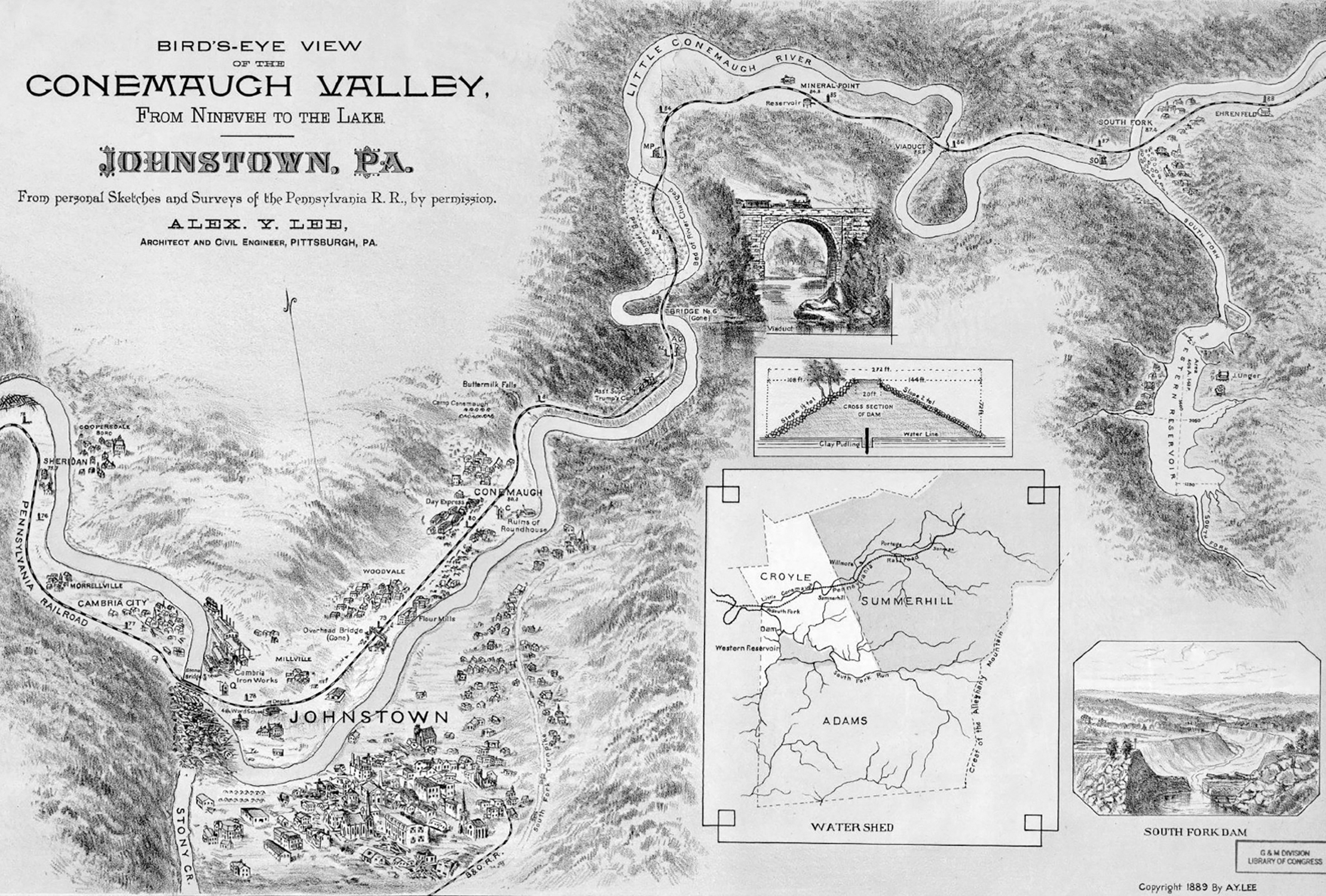

Thats the story they liked to tell, anyway, in and around Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in 1889. Little Gertrude Quinn was only six that year, and even she, like the fictitious Johnny, knew how important iron and steel and the Cambria Works were to the life that she, her family, and everybody they knew were living here in the deep valley of the Conemaugh River under the abrupt rise of the Allegheny Mountains.

At about 3:00 P.M. , on May 31, 1889, an explosion of previously unimaginable force would smash that world. Twenty million tons of towering water, released all at once from high above the town, falling with gathering momentum down the narrow Conemaugh Valley, picking up houses, factories, forests, railroad tracks, locomotives, livestock, and human beings as it came, would arrive with a roar like nothing heard in Johnstown before. In moments, and then in the horrifying hours that followed, that gigantic, raging thing would destroy thousands of lives, knock down and carry away hundreds of buildings, spread raging chemical fires, and send little Gertrude Quinn on a horrifying journey.

It would be the end of the world. And the Cambria company, which had made that world, would be powerless to stop the destruction.

Nobody in Johnstown could see what was coming, of course. Theyd grown used to the world the Cambria company had made, a new world. At six, Gertrude Quinn wasnt old enough to remember that not so long ago, there hadnt been much in Johnstown but a sleepy farming village. But grown-ups could remember. That village had been succeeded by a canal town that seemed, for its time, comparatively bustling and excited, but by 1889, the former excitement seemed like nothing. The canal was defunct, replaced by railroad trains that chugged and screeched day and night along steel rails on the ridges: the foundries and steel mills on the riverbanks were going almost all the time, their fires sending up a perpetual haze of stink and emitting a steady pound and roar. Men drenched in sweat, their skins darkened by sooty smoke, moved quickly, athletically, on those factory floors, shoveling coal, carrying molten metal in long ladles, operating the huge, dangerous rolling machines that pushed out miles of steel rail.

Steel rail. Thats what made not only Johnstown, Pennsylvania, but the whole nation run, and run in a new way. In a single generation, the United States had become a sprawling, booming power built on speed, noise, and engines, on electricity and steam, on iron, and especially on steel, cheap steel, hundreds of thousands of miles of rail carved by rolling mills from the soft, glowing product, cooled to an intense durability, and laid down for track that let engines haul hundreds of cars filled with still more steel, steel for bridges, for buildings, for a whole quickly rising America where dazzling fortunes were made and hard factory jobs were plentiful.

All that had begun here in western Pennsylvania. The Cambria company made not only the world that Gertrude Quinn and other Johnstowners knew but the new nation, too. By 1889, the companys vast rolling mill in Johnstown, with its many related factories and stores and yards, a virtual city of pounding, smoking, roaring work spreading along a tributary of the Conemaugh River known as the Little Conemaugh, was not only among the largest iron and steel operations in the world, but also the leading innovator in steel production. From the fictitious Johnny of the local joke to the real little girl named Gertrude Quinn, from the workers on the factory floors to the executives in the big houses to the bosses and investors living in glittering splendor in Pittsburghonly an hour-long train ride west, these daysreally everybody in western Pennsylvania knew that all kidding aside, Cambria Iron really did, in many ways, make the world they lived in, locally and nationally.

And steel spawned other enterprises. Entrepreneurs had come to the Allegheny valleys to found not only iron and steel factories but also the mills that added value to steel: the Gautier Wire Company, for one, in nearby Woodvale. Factories enabled by the steel boom made things as seemingly unrelated as woolens. Almost everything was tied up with the loud, relentless pace of the iron and steel economy, and in Johnstown the Cambria company owned most of those secondary factories, too. Iron and steel, so much of it made right here in western Pennsylvania, made America.

The most famous of the innovators who had become millionaires in railroad, telegraph, iron, and steel was Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie was changing the way all of big businessa new term in the 1880swas conducted, and he was a man of western Pennsylvania. His own mills were located not in Johnstown but outside Pittsburgh, yet by 1889, innovations made by the author of The Gospel of Wealth, putting smart investment ahead of hands-on operation, as well as his astonishing adroitness in forming monopolies, had begun changing how things were done even by the all-important Cambria company. Carnegie loved the Allegheny Mountains and the Conemaugh Valley. He thought on planes higher than those represented by mere steel and business: he was interested in beauty, nature, contemplation, relaxation. Those interests, as put into practice on a mountain above Johnstown, were about to have an unintended, disastrous effect on the city and the entire Conemaugh Valley.

L ittle Gertrude Quinns family wasnt in the steel business, not directly. Shed had a great-uncle whod worked as a steelworker, but the Quinns neither labored as millworkers nor managed labor as executives nor counted their millions as investors. The Quinn family were store owners, and prosperous ones at that.

Dry goods: the business had been begun under the little girls maternal grandfather, a Johnstowner of German extraction named Geis, now retired, when the town was far quieter. The store had thrived then, and Gertrudes father had taken it over, and with the boom in factory life and all of the big changes in town, the place had become quite upscale. The Quinns and Geises owned other properties now, too, right in the center of town.

By six, Gertrude had distinguished herself as an unusually sharp and observant little girl, full of life and curiosity, at times inclined to be naughty, and she loved the family store. Clerks and customers alike treated the Quinn children as important personages, and with few opportunities for organized entertainments, the little girl treated the store as her own personal show. It was brightly lit, and people not only came and went but also hung around, exchanging gossip. She especially liked a line of needles the store carried. They came in small bronze packages, on which were printed the faces of Gertrudes beloved Papa, Mr. James Quinn, and her uncle, a partner in the business. Gertrude adored Papa. Both men wore the perfectly trimmed Vandyke beards of the day: on the needle tins, the bronzeness seemed to her to make them look very fierce and strong.

Gertrude would steal these needle packages and proudly hand them out to her playmates. Her father didnt know that her friends mothers were getting their Quinn store needles free.

Gertrudes mother was, to the little girl, always a smiling, protective, and devoted presence, but in fact Rosina Quinn was anything but the stereotyped angel in the house of Victorian ideal. Rosina, born Geis, was a smart and efficient person of business. In about 1859, her own father, having founded the company, took Rosina out of boarding school at the age of fourteen and set her up with a store of her own, right on Main Street, with an inventory of four thousand dollars worth of merchandise. No woman in Johnstown had run a commercial establishment before, much less a teenage girl. With her sixteen-year-old brother, Billy, doing the books, Rosinas store took off. She was a tough dealmaker with a comprehensive grasp of all things commercial. The store flourished throughout the Civil War years, and Rosina didnt even give up the business with her marriage to James Quinn.