Authors Note

T HIS is the first full accounting of the Great Boston Molasses Flood. It was not simply a disaster that occurred on a mild January day in 1919, but rather a saga that spanned a decade, from the construction of the tank in 1915 through the conclusion of a huge civil lawsuit in 1925.

There are no other books on the subject, and little has been written on the ood at all, save for a handful of magazine articles and newspaper retrospectives that have appeared sporadically through the years. A few works of childrens fiction allude to the event, but the story lines of these books generally focus on fun and adventure in a fanciful world of molasses, rather than depicting the event as the tragedy it was.

It is probably not surprising, then, that the disasteran event that knocked Prohibition and the League of Nations out of the headlinesis little more than a footnote on the pages of Americas past. Even in Boston, the ood today remains part of the citys folklore, but not its heritage. A small plaque in the North End marks the site of the ood (placed there by the Bostonian Society in the mid-1990s), and tourist trolleys slow down when approaching the area so the driver can point out the location. One of the converted World War II amphibious vehicles that transport tourists through the downtown streets and into the Charles River, part of Bostons renowned Duck Tours, is named Molly Molasses, but most who learn about the citys famous landmarks leave with little actual knowledge about the molasses ood.

Beyond these references, the story of the ood has remained elusive, surfacing occasionally in the folksy myth recounted by cab drivers and citizens alike that on hot summer days, for years after the ood, one could still smell the sweet, sticky aroma of molasses.

There may be several reasons for this indifference.

One is that, in a city defined by so much compelling and pivotal history, from the founding of Plymouth Colony to the Battle of Bunker Hill, from the Abolitionist movement to John F. Kennedy, perhaps it is difficult to make room for an event in which ordinary people were affected most. No prominent people were killed in the molasses ood, and the survivors did not go on to become famous; they were mostly immigrants and city workers who returned to their workaday lives, recovered from injuries, and provided for their families.

Another reason the ood has never attained lofty historical significance may be because of its very essencemolasses. The substance itself gives the entire event an unusual, whimsical quality. Often, the first reaction of the uninformed when they hear the words molasses ood is a raised eyebrow, maybe a restrained giggle, followed by the incredulous, What, youre serious? Its really true?

But perhaps the biggest reason the ood has not claimed its proper place in Bostons history is because, until this book, the storyif known at allhas been mistakenly viewed as an isolated incident, unconnected with larger trends in American history. Dark Tide makes those connections.

I have done presentations about the molasses ood to hundreds of people, and when they hear the entire story, wrapped in its full historical context, they are almost always fascinated and anxious to delve more deeply into the topic. Afterward, the inevitable response is: Why didnt I know about this and where can I learn more?

Undoubtedly, some of that interest comes from a visceral reaction to the disaster. The molasses ood was a tragedy (twenty-one killed, 150 injured), it occurred in a great city, contained a whodunit element (why did the tank collapse?), spawned in its aftermath a true David vs. Goliath courtroom drama, and created a collection of heroes that saved lives that day and sought justice afterward. These are crucial pieces of any good story, elements that grip the imagination and fuel additional interest.

But the real power of the molasses ood story is what it exemplifies and represents, not just to Boston but to America. Nearly every watershed issue the country was dealing with at the timeimmigration, anarchists, World War I, Prohibition, the relationship between labor and Big Business, and between the people and their governmentalso played a part in the decade-long story of the molasses ood. To understand the ood is to understand America of the early twentieth century.

The ood, therefore, was a microcosm of America, a dramatic event that encapsulated something much bigger, a lens through which to view the major events that shaped a nation.

That is why, when people hear snippets of the molasses ood story, they invariably want to hear more.

That is why, finally, the full story needs to be told.

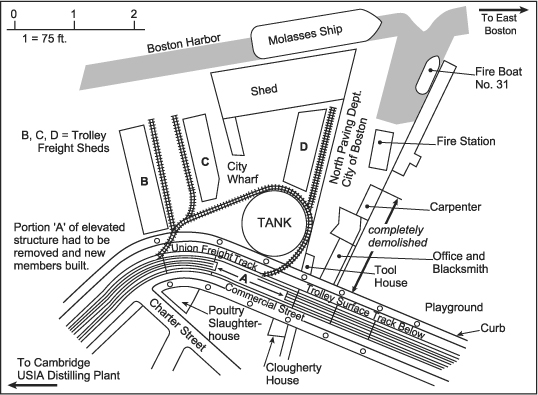

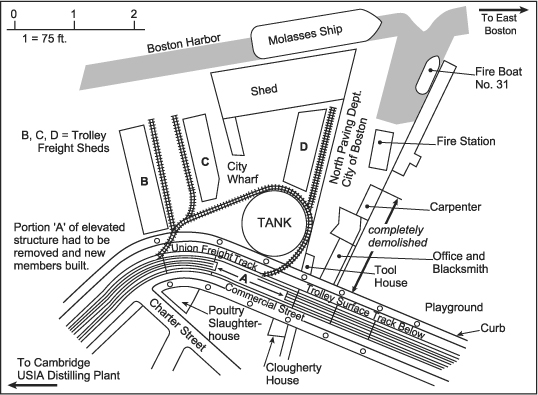

Illustration shows close-up view of molasses tank and waterfront area, including the way molasses ships docked and pumped their cargo through a pipeline into the tank. Configuration of surface-level spur tracks showed how molasses was transported from tank to USIAs distilling plant in East Cambridge. The proximity of the Clougherty house to the tank and the overhead railroad tracks is also shown.

(Map by Sarah Gillis, adapted from map published in Engineering News-Record, May 15, 1919)

PROLOGUE

ISAACS DEMONS

Boston, Late July 1918; 2:30 a.m.

Isaac Gonzales knew what a terrible thing it was to be afraid at night. Night fear had robbed him of sleep and drained him of rational thought. Tossing and turning in the dark, his wife asleep beside him, he was unable to block out the horrible images that ooded his mind and wracked his body with terror. And, once again, his fear drove him from his bed, from his home, and into the night.

Now he was running hard through the darkness of Bostons North End, his heart pounding, sweat rolling between his shoulder blades even in the early morning hours. Summer was strangling the city this last week in July, and the cramped tenements and narrow streets threw off heat long after sunset. Isaac threw off fearit pulsated from his body in wavesand he felt an odd mixture of shame for his inability to conquer it and satisfaction for his willingness to fight it.

He could feel the buildings pressing in on him, his legs becoming heavier and his breathing more ragged. Sprawling warehouses, cheap wooden storefronts, and dilapidated tenements stood shoulder to shoulder, snuffing out the moonlight from Isaacs path. He saw no other people, but he could hear scattered coughing from the at rooftops where families had dragged their bedding, escaping the stiing confines of their tiny apartments in search of sleep. He could feel their presence, and he imagined these rooftop guardians watching him, as his rubber-soled boots thumped against the cobblestones.

PROLOGUE

PROLOGUE