The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

It is the noblest offering that nation ever made to nation.

What we are doing will be an example to be followed by some abroad who might shut their hearts to the calls of their neighborsit will prove a seed sown in fruitful ground.

This is a story about hope, generosity, and soaring goodwill against a backdrop of nearly unfathomable despair; and like any story with such powerful themes, its lessons run deep and its ramifications are measured in decades rather than days.

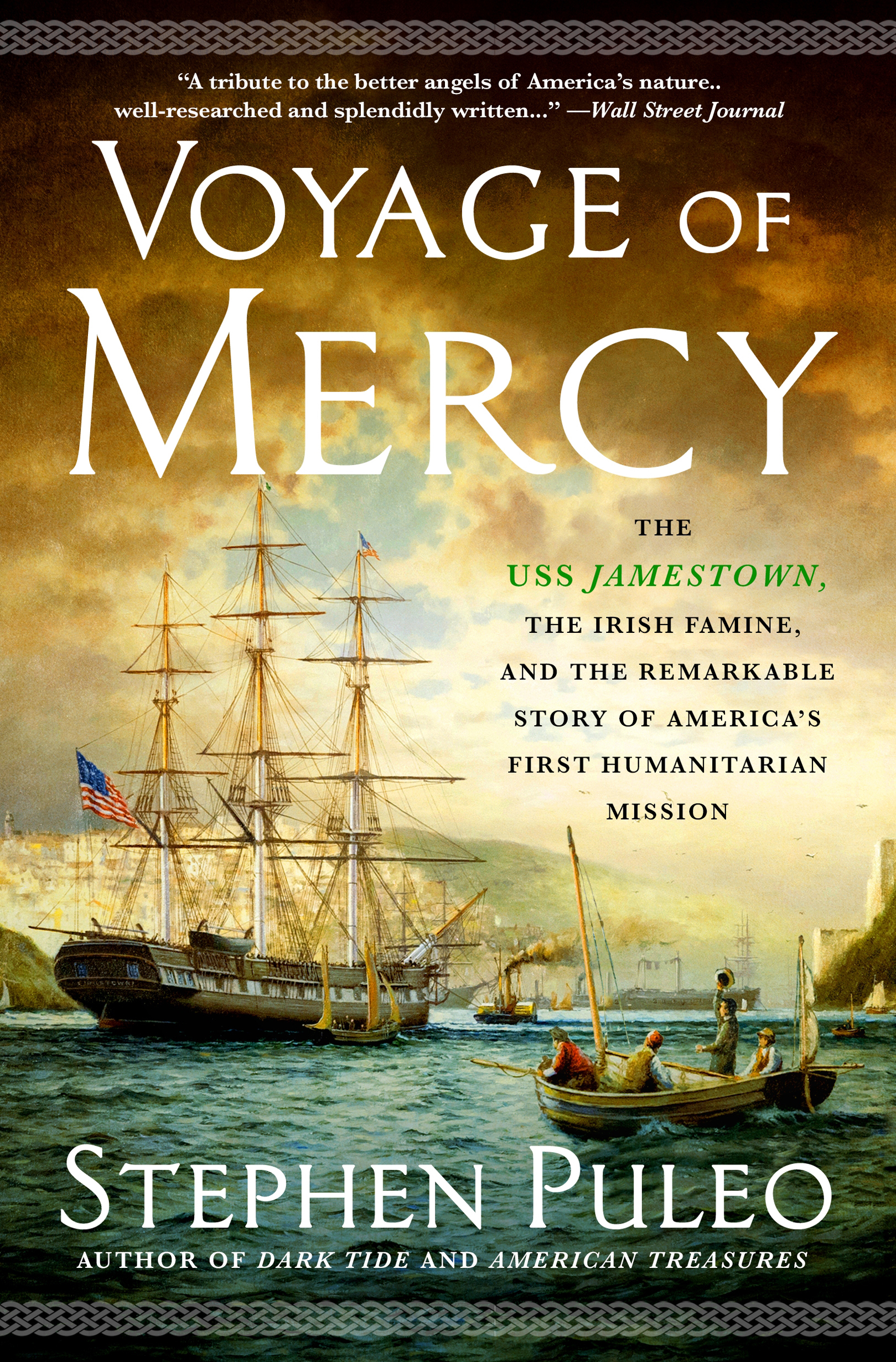

Voyage of Mercy recounts for the first time the remarkable and unprecedented relief effort by the government and citizens of the United States to assist Ireland during the terrible famine year of 1847; remarkable because the mission undertaken by Captain Robert Bennet Forbes and the crew of the USS Jamestown to deliver tons of donated food to Ireland was the first step in a monumental effort that involved contributions from citizens of virtually every community in the United States and the official imprimatur of the U.S. government; unprecedented not only for the size and scope of American participation, but also because it was the first time the United Statesor any nation, for that matterextended its hand to a foreign neighbor in such a broad and all-encompassing way for purely humanitarian reasons. Prior to 1847, the bulk of interaction between nation-states consisted mainly of warfare and other hostilities, mixed with occasional trade; the entire concept of international charity existed neither in the moral consciousness nor as part of the political strategy of monarchs or elected leaders. If anything, such a gesture toward a foreign nation would likely have been viewed as a sign of weakness.

The Jamestown mission was, in modern parlance, the tip of the spear, the most visible and most celebrated component of Americas first full-blown charitable mission. The U.S. relief effort encompassed far more than the Jamestown, but it was the historic voyage of a retrofitted warship embarking on a mission of peace that most visibly symbolized the widespread willingness of the American people to offer up enormous stores of food and provisions to assist victims of the Irish famine.

The voyage itself and the subsequent outpouring of charitable relief captured hearts and minds on both sides of the Atlantic, of wealthy and poor, of royalty and commoners, of poets and politicians. In addition, the events of 1847 have served as the blueprint and inspiration for hundreds of American charitable relief efforts since, philanthropic endeavors that have established the United States as the leader in international aid in total dollars and enabled it to assist millions of people around the world victimized by famine, war, and catastrophic natural disasters.

Two compelling individuals occupy the center of this story.

Sea captain Robert Bennet Forbes of Boston was one of the most dynamic, determined, resilient, adventurous, well-traveled, generous, and interesting men of his ageor any age, for that matterand until now, his story has never been fully told. I am grateful that he was also an excellent, frequent, and descriptive writer, able to relate both meaningful context and colorful details, understand the nuances of human nature as well as his own virtues and shortcomings, and express himself with passion, pathos, drama, and humor. In addition, he was the consummate collector and keeper of documentsa bit of a hoarder, actuallywhich has provided us with a rich trove of what others thought about him, his mission, and his world (see Bibliographic Essay).

The Reverend Theobald Mathew, known best as Irelands Temperance Priest, was the heroic and indomitable figure on the Irish side of the Atlantic, fightingthough mostly in vainto save the lives of his starving countrymen and convince British authorities of the speed of the famines onslaught, the extent of its horrors, and the desperate need for additional relief. In the decade before the famine, Father Mathew had achieved fame on both sides of the Atlantic for his efforts to convince hundreds of thousands of Irish to sign his temperance pledge; in fact, history records his crusade against drinking and alcoholism as his signature achievement. But his work in the trenches during the worst of the famineoffering food, shelter, medical care, and comfort to those suffering from near starvation and debilitating diseasewould forever endear him to the Irish people, especially those from his home parish in Cork city. Still revered in his native country today, Father Mathew, like Forbes, is little known in the United States, despite a lengthy and controversial visit to America shortly after the famine. Im grateful for the opportunity to tell his story.

What truly inspired me about this story were the actions of what Ill call thousands of other real-life characters, who together make up a single collective character of sorts: the American people. I had known something about the Jamestown voyage before researching this book, but I was completely unaware of the enormous scope of the U.S. relief effort to Ireland in 184748, the widespread generosity of Americans from all walks of life during a time when the very act of survival and supporting ones own family presented a grueling daily challenge and was far from guaranteed.

That Americans from across the United States contributed to Irish relief was extraordinary enough, but it was the nature of most of their donations that was most impressive. This was not a matter of entering credit card information or dropping off a bag of canned goods, though these are certainly generous acts in their own right. While many people sent small amounts of money, farmers often donated crops they had grown themselves to sustain their loved ones. They furrowed the ground, laid the seed, nurtured the plants, and harvested the cropsbeans, corn, barley, wheat, and much more. Then those who chose to help the people of Ireland took a portion of those goods, packaged them in burlap sacks or wooden kegs, and delivered them by horse-drawn wagon to river ports, where rafts and small boats carried them to larger ships that navigated broader rivers and the Erie Canal. From there, the food made its way to major Atlantic ports like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, where dockworkers loaded it upon ocean-sailing vessels bound for England and Ireland.

Farmers and planters in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Tennessee, Maryland, Virginia, western New York, and western Massachusetts, in the mid-Atlantic states, across the South, and along the Mississippiall of them literally took food out of the mouths of their own family members, or food they would normally sell at market to buy goods for their cabins and farms, and shipped it to strangers thousands of miles away.