Contents

Its all about songs.

Without the songs we have nothing. All those magical moments that make music fans swoon the singles, the albums, the concerts, the books, the DVDs, the liner notes, the dance-floor fillers, the car tapes and the carefully compiled CD burns, the posters on our bedroom walls all this joy simply would not exist without songs.

For me, it started with songs. I remember listening to White Room by Cream on a radio built into the bedhead in a motel in Wagga Wagga while my brother shivered with chicken pox and my mum mopped his brow from a Tupperware bowl. I remember hearing Pretty Woman by Roy Orbison on a brown transistor, sitting beside the Goulburn River with my dad, fishing and twiddling that radio dial. I remember my next-door neighbour Merrilee dancing to Love Me Do, and I remember singing Pamela Pamela by Wayne Fontana in front of my bemused Grade Six class.

I dont remember much about my HSC biology classes, but I vividly recall huddling around a neglected Bunsen burner in the back of the science lab with Roger and Andy, passionately debating the much maligned 1970 Bob Dylan album, Self-Portrait. We didnt care that the critics hated it or that most serious Dylan fans were confused or outraged. We loved it, and we loved it because of the songs.

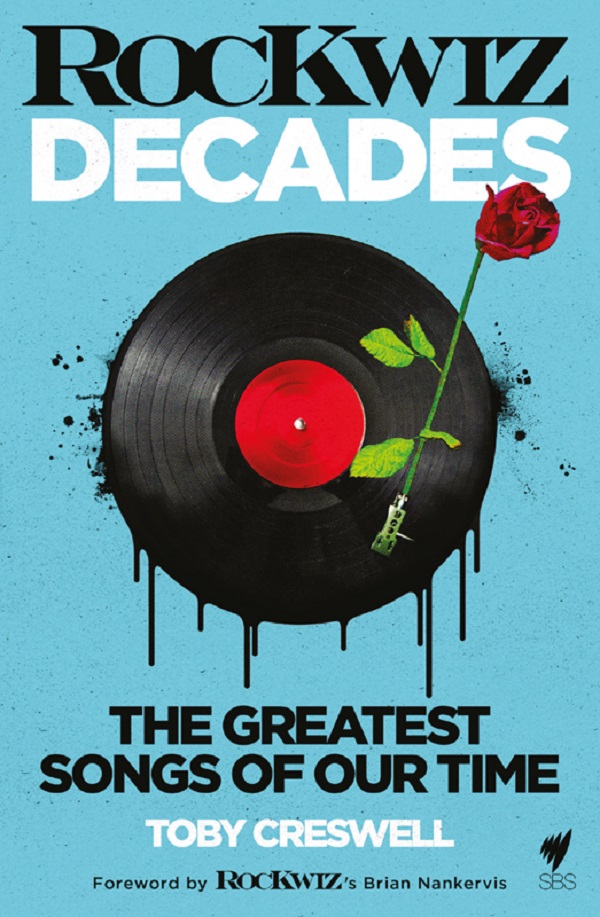

RocKwiz Decades was first released as 1001 Songs in 2005, the year that RocKwiz began screening on SBS television. I remember buying the book and instantly realising that not only was it a goldmine of eye-opening, essential information but, just as importantly, it was also filled with smart, strong opinions from a writer Id respected over many years. It has been an incredible resource in the creation of the RocKwiz scripts and questions.

There are old favourites in here, songs I wasnt familiar with, plenty of contemporary artists and, of course, songs that you dont really want to hear, but youre happy to read about. I dont need to listen to Relax by Frankie Goes to Hollywood again, but I was fascinated to read that it has the same beat as Saturday Night Fever, that the heavy breathing and the stuttering musical passages were a nod to Donna Summer, and that guest musicians included members of Ian Durys Blockheads and Steve Howe from Yes!

So, on behalf of all the fine folk at RocKwiz, I hereby take great pleasure in lending our full support, with true excitement and much gratitude, to this edition of Tobys book RocKwiz Decades.

Brian Nankervis

I believe it was the American singer/songwriter Beck who observed that music made in 1969 could not have been made in 1960 or that music we listened to in 1979 could not have been imagined in 1970 and so forth. So much of our history is written in song, our lives are traced through the tunes on the hit parade. With each decade comes a particular sensibility and style that befits the times.

The 60s were a time of liberation; of innovation, of new ideas and new ways of life. At the beginning of that decade in music you had the teenage dreams of Carole King and the Beach Boys capturing a time when the guns of world war had stopped, when the world was full of new machines, new technologies.

Then came the Beatles. They were a completely new phenomenon; new sound that came with a fashion code but, more importantly, the Beatles made pop music the most important art form in the world. Bob Dylan chimed in with his Beat-inspired poetry and the Rolling Stones showed up with the sex and the drugs. In 1965 rock & roll stepped up to a whole new level. Songwriting was no longer Tell your ma/Tell your pa/Our loves gonna grow/Ooh wah ooh wah. It could now be a complex way of telling personal stories or conveying information.

In the mid-1960s drugs, especially LSD, influenced a further subculture, and with those drugs came the creative notion of taking a journey to the centre of your mind. It was the idea of really looking through rose-coloured glasses, of changing what reality actually was. In this psychedelic era, songs went from being 3 minutes in length to upwards of 20 minutes. After two years of psychedelic, Bob Dylan went to Nashville, the Stones made Beggars Banquet and it was all back to the roots; old school rock & roll.

The Vietnam War, which raged through the 1960s, defined much of the music of that era. Straight-up folk songs like A Hard Rains Gonna Fall gave way to music that was more expressionistic. Jimi Hendrix was a key figure here. His guitar playing, the sound of the feedback and the rough and raw guitar lines expressed, in their novelty, a new world of chaos and danger and anarchy. Hendrixs music whether the song was specifically about something or simply a love ballad drenched in this maelstrom, gave context to the times. We were all living through a world that was fuzzy around the edges and likely to explode at any time.

The Rolling Stones track Gimme Shelter which was released in 1969 is the perfect song of that era. Backup singer Merry Clayton wails about a fire thats sweeping our lives just a shot away, just a kiss away. That same year Brian Jones died and the Rolling Stones played Hyde Park, releasing hundreds of white birds in his memory. A few weeks later half a million kids created Woodstock and the Woodstock nation.

The 60s had started as a time of so much promise but they ended with Charles Manson in the Hollywood Hills, with the tragedy of the Stones Altamont concert and with the end of the Beatles.

The 70s was a period of decadence, of polymorphously perverse sexuality, of hard drugs instead of acid. It was a time of struggle and the songs reflect that. In the last few years of the Vietnam War a whole new mood descended on the US. Bruce Springsteen later captured that better than anyone with his songs such as Racing in the Street and Born in the USA. Vietnam became not just a military expedition but a state of mind. Its effects were felt in the rush of heroin to American streets (Im Waiting for My Man by the Velvet Underground) and in the collapse of optimism for young people (The Pretender by Jackson Browne).

In the middle of the 70s, after the oil shocks caused a global recession and Richard Nixon had fought a war on the hippies, a solution came through. Or rather two solutions: punk rock and disco music. Punk was a throwback to the early 1960s but in England it had a different context. Punk was about the voice of the working class, it was the last ditch attempt to use music for political change.

Obviously the Sex Pistols and the Clash were highly political in everything they did but there were many others: Elvis Costello, the Specials, Midnight Oil, Billy Bragg, X-Ray Spex, Sham 69 and a few years later in the US, Black Flag and Fugazi.

Disco was mostly the hedonistic sound of the clubs but it could also, in the hands of Chic and others later, be an authentic voice of the streets. Machines There But for the Grace Go I, the Isley Brothers Fight the Power, Heaven 17s Ball of Confusion and the Temptations Law of the Land all express the pressure of oppressive governments and the struggle in the streets against poverty, drug abuse and crime.

In the 1980s, with the recession fading, there was an upsurge of rock & roll. The songs were confident and brash and often could be witty and sexy. This was the new sound of black America and it seemed to get into every place on the planet. Great artistry was the hallmark and it was never less than innovative.

In England you had the Blitz kids in the south enjoying the new prosperity. In the north there were the more depressive types, but nonetheless great music came from the likes of New Order. This group from Manchester in the 1980s profoundly changed music.